In Western Spain, a November snowfall is a little miracle. And as I write, it’s happening out there. The children at my household, my younger siblings and our guests for the weekend, are ecstatic. Typing on the computer with a blanket on my knees, I can feel a little like the Ray of the group, listening them play and appreciating the breathtaking beauty of the snow while feeling the warmth of my home.

I woke up this morning to the adventurous, diamond-like, pure whiteness that has transformed everything around me, trees, roofs and roads, the mountains and the sky. Very fittingly. As I’m writing this, the Catholic liturgical year ends. Tomorrow, a new Advent will begin, a time for purification, cleaning our hearts and making room for the birth of Christ.

To me, it is a very promising time, and I feel blessed. But it could be otherwise.

Sometimes, it only takes a poisonous drop to dirty an entire well. Sometimes, your home, or your world, is not so warm. Perhaps you’re trapped. Perhaps, you never realized, perhaps, you always knew. Sometimes, you’re pondering vital matters, fearing your mistakes, or clenching your teeth because someone is not there. Suffering, as I was last year.

On an even more basic level, can you imagine what would it take to survive out there, in the open? Being homeless, pursued, like a refugee or a fugitive in a hostile country? And it could happen. In a way, we have tamed the world, but it’s still strange and wild, and that wildness is sometimes just one step or misstep away.

If you have watched The Promised Neverland (spoilers ahead), you do know all this.

Sudden reveal or not, the stomach-churning horrors of this world and of our own hearts will rise to meet us, sooner or later, and it’s impossible to unsee what we have seen. A November snowfall may be a dreadful image. The cold, the scarce resources getting buried, and your destiny stretching farther and farther from your reach.

Sometimes, it’s even worse. It’s winter inside us, a long winter, where we’re chased by interior pursuers, and love is a memory, a lie, or a wound. The coming of Thanksgiving, of Christmas, of another year, and feeling like this while everyone else is celebrating around us, may be painful, a grief endured.

But for me, that reality doesn’t taint the beauty of this moment. I’m certain that it’s not an illusion. It’s real.

I know that there’s something difficult to swallow about that. How in the world can I square the beauty and the ugliness? Not by pushing these thoughts aside. Not by convincing myself somehow that those who are out in the open deserve it for one reason or another, while I don’t. And, well, not by turning into a psychopath (I hope).

Finding a way to take joy in a cold world, burdened by ambiguous memories and by the wounds of betrayal, sounds a lot like the second season of TPN, right? Again, spoilers ahead.

Do you remember those happy first four episodes, before everything (arguably) went wrong? I do. In fact, I enjoyed them so much that I’m not bitter about the rest. I wasn’t a manga reader at the time, so I didn’t have the feeling that I was missing something. The opening, “Identity”, evoked a feeling of hopeful rebellion in the name of a bright and pure ideal.

At its best, TPN, my favorite show, is a story with clean eyes and a mighty heart. A show that asks us to hope and fight for a life that is not disgusting, but radiant and burning. So that our bonds are honored, this deep and mysterious world is revealed, and our precious family, which may include everyone, is saved. It has the humble epicness I try to bring from my life in God to my eventful life and my everyday world.

But, sometimes, my everyday world feels more like Welcome to the NHK, the perfect portrait of the life I would never want to have. Addiction, exploitation, ambiguity. Tainted motives, egoism, filth. Sloth, regret, isolation, self-victimization. The feeling of ugliness, of repugnance–all secretly given consent in the intimacy of one’s soul.

I don’t have Tatsuhiro’s problems, but I know the feeling. As with other emotions, anime can depict it poignantly and uncomfortably. In the tradition of Paranoia Agent or Lain, NHK is a very disgusting show, and it ought to be. After all, Inside Out, whose Aristotelian wisdom I admire, says that disgust’s purpose is to prevent physical and social poisoning.

This may sound harsh, especially the second part, but it is true. Even more so, it is essential. We need these unflinching portrayals of what happens when free rein is given to vulgarity, shamelessness, lack of hygiene, lust, uncontrolled urges, carelessness, arrogance, sloth, despair or madness, as happens in many dark corners of our world.

But this essential personal and social defense system may go overboard. That pressure is sometimes helpful, but it is also sometimes crushing. As NHK tells us, not even pure hate hurts as much as seeing it in the gaze of others. My own disgust has the purpose of helping me avoid Tatsuhiro’s downfall, physically, morally and socially. But sometimes, it weighs on me.

Disgust unites the instinctive with the feeling of legitimacy, the irrational with the rational, and is hard to uproot. We are disgusted for things that are perfectly innocent, a matter of taste. Or we show rejection when we need to show affirmation and grace. Disgust is what almost killed Tatsuhiro. And disgust is what almost killed Ray.

So, what then? I struggle to face disgust like Peter and Emma. No, not that Peter. Stay tuned.

TPN‘s first chapter taints its world. A young child, loved and valued by her siblings, is betrayed and killed by the woman she considered a mother, and is given as food to grotesque alien creatures. Her corpse, stripped of clothes, is stored in a tube, floating, with open eyes, and pierced heart. And the children see it.

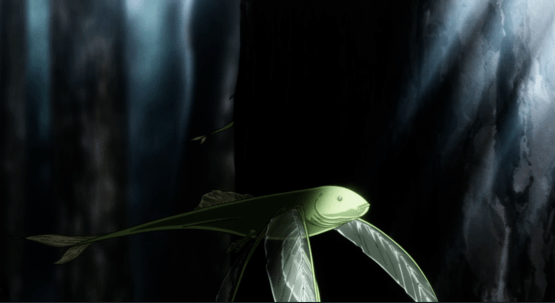

An experience like that may poison an entire life. The mere suggestion that the world could ever make sense again after that can twist the stomach and cause a wave of disgust and rebellion to rise up. Imagine just how disgusted Emma must feel at all that. The logic of prey and predator. The act of killing. And the flower that pierced Conny’s heart, absorbing her blood, its white petals turned red.

And yet, in season two, Emma and her group are living with Sonju and Mujika, two demons who don’t eat humans due to a religious taboo, and she asks Sonju to teach her the art of hunting. So strict in avoiding committing evil acts even to save her life, Emma has deduced that this is licit, helpful, necessary even. And there she goes.

It’s hard. We can see it in her eyes, in her brow, in her whole demeanor. Sonju tries to alleviate her burden. But, like Hachiken in Silver Spoon, Emma insists on going through it all. The ritual. The technique. The flower. The thanksgiving. What is she feeling? Again, I can only wonder. “I’m okay”, she says. Yeah, right. What in the world is this girl doing? You may have your guesses. But I think she’s making the world pure again.

In my very first post at Beneath the Tangles, I pointed out some parallels between the early Church and the orphaned flock Emma and Ray are guiding by the end of season one. Into a new world without the old certainties, dangerous but with real hope. One where only the purest of ideals can bring us to our destination.

When the early Church faced its first great division, Christ asked Peter, St. Peter, to do something he found repugnant. He was to kill and eat.

Like Mujika and Sonju, St. Peter was under a God-mandated taboo. An interesting aspect of the Old Testament are these norms of Mosaic ritual purity that are observed by the people of Israel even to this day. There was a detailed list of things they were to avoid, and only the most pure offerings could be given as a sacrifice to God.

Looking at the list of taboos we see, in general, things that convey to us the impression of poison, putrefaction, disease, the decomposition. Also, there’s the interior of the body, waste, and the dead. And lastly, those animals that are less likely to symbolize something elevated: camels, ostriches, octopuses and pigs.

This list was intended as a metaphor for inner evil and inner purity, symbolized by visual cleanness of lambs and doves, of the bread that came down from Heaven, the red blood of sacrificed animals and of wine or the purifying power of water. Once, God used disgust to teach His people that they should avoid what is wrong.

Thus, Israel learned that they, the People of the Promise, should not adopt the idols and behaviors of the pagans, “the nations”. To be associated with them in a way that could lead, even remotely, to Israel’s absorption by another worldview was also a cause of impurity.

To enter the house of a pagan, for example, was forbidden by the Mosaic Law. You may recall how the centurion asked Our Lord to heal his servant without entering his house. Or how the Sanhedrin members carefully avoided entering Pilate’s fort during the Passion. It was not a racial matter, as everyone could be a Jew, provided that they were circumcised, submitted to the people of Israel, and joined the Covenant, as (say) Ruth did. But it was there.

If ritual impurity were to happen, Israelites were to go through a purification rite. Until they did so, they couldn’t offer sacrifices or participate in their celebrations. It was a social, moral and religious system that set them apart. As with Sonju and Mujika, they were different. And as with them (or at least Sonju), the Israelites often didn’t understand the deeper reasons for the taboo. But they trusted and obeyed.

While the unilateral obsession with the external observance of ritual purity made the Pharisees into everything we associate with that word now, the system served its purpose. Israel’s observance of these rites and taboos would allow the Apostles and others to understand what Our Lord’s mission meant, from His baptism to His final sacrifice.

On Earth, He usually observed most of the ritual traditions of His people, commanded by God, while exercising His kingly sovereignty over these precepts when He needed to. And when He died in Jerusalem on the first Good Friday, all the faithful Israelites who observed the precepts of Deuteronomy and Leviticus were right there.

The Apostles were stunned by their Master’s approach. When asked, He pointed out that what comes out of the belly goes to the latrine. What awakens the disgust around us, when it’s external, can be purified by external means. Socially, mechanism of approval and disapproval are appropriately used to favor cleanliness, health and social courtesy. But what makes humanity truly impure, individually and socially, is the sin that is within.

With Christ’s death on the Cross, the time for those symbols was over. The miracle and the promise would make the use of some of the things that were previously symbolic literal. The water of baptism, in His hands or those of His followers, would cleanse the soul. The bread and wine, by His word, would turn into His real body and His real blood.

In His Ascension, He commanded His disciples to go to all the nations, to the pagans, and preach the Gospel, baptizing in the name of the Trinity. But changes are hard. And like Emma, Peter had to go through a shock therapy of sorts.

In the book of the Acts, we’re told that Peter went up on the roof to pray in the course of one of those early journeys at this time of uncertainty. As the meal was being prepared, he had a vision. “He saw heaven opened and something like a large sheet being let down to earth by its four corners. It contained all kinds of four-footed animals, as well as reptiles and birds. Then a voice told him, “Get up, Peter. Kill and eat.”

Peter being Peter, he was sure to argue. “Surely not, Lord!” Peter replied. “I have never eaten anything impure or unclean.” The voice spoke to him a second time, “Do not call anything impure that God has made clean.” This happened three times, and immediately the sheet was taken back to heaven”.

Three men stopped at the gate. The Spirit instructed Peter to go with them and met Cornelius, a pagan centurion. Cornelius was making the unprecedented move of inviting the Apostle into his house, after an angel ordered him to. And Peter came.

From there, the full acceptance of non-Jewish members of the Church, without the observance of the ritual aspects of the Law of Moses, would begin. This was the main issue addressed at the Council of Jerusalem, which settled this first division.

Our faith is not one of sentimentality. There are many things that we have to swallow. Humanity is ill and in danger of eternal death. Meanwhile, we live in this world, which has its rights. We grow. We fight to defend ourselves. He who doesn’t work may not eat. Discipline is enforced, also within the Church. God does not want pearls to be thrown at pigs, or for the Prodigal Son to be sitting in the mud, or for the guest to enter the King’s banquet unprepared. Lust, common insults, gossip, vulgarity or superficiality may very well kill us.

As we journey, pilgrims on this Earth, strangers in strange lands, we are to trust Christ. Especially, when our own disconcerting, stomach-churning discourse of the Bread of Life comes. Our disgust is healthy, but we don’t use it to just cut others off from our lives. Or fall into despair, or close our eyes.

Rather, like these fugitives, these young pilgrims walking toward the advent of something new, we look to our radiant ideal of purity to separate the thing that we reject from the person who does it or suffers from it, be it ourselves or others. We aspire to, and cooperate with, a renewed cleanness.

Because God is pure, and He touches lepers, cleanses festering wounds, chooses the stables of Bethlehem, washes our feet or shows beauty through the blood of the Passion. Like a reverse Vida flower, we wash our robes and make them white in the blood of the Lamb. What was lost will be restored, and a new beauty, a new integrity, will emerge.

It is because of this that, as with Emma, the danger and suffering don’t taint the wonder of this world. We will kill and swallow. It will be hard. But then we will live.

We may always receive again this beautiful world, this new, adventurous life, as a child welcomes an unexpected snowfall. Or Christmas. In purity, in freedom, come what may. There is hope.

Happy Advent.

The Promised Neverland can be streamed at Netflix, Hulu and Crunchyroll.

- First Impression: YATAGARASU: The Raven Does Not Choose Its Master - 04.15.2024

- First Impression: Viral Hit - 04.10.2024

- First Impression: Unnamed Memory - 04.09.2024

“We need these unflinching portrayals of what happens when free rein is given to vulgarity, shamelessness, lack of hygiene, lust, uncontrolled urges, carelessness, arrogance, sloth, despair or madness”

Read this and immediately thought of the book of Judges. Now I’m imagining an anime adaptation of Judges and yeah, it would fit right in.

I really liked this.

I’m very glad! Thank you for your comment.

[…] Emma, Kill and Eat: Advent and The Promised Neverland […]

[…] Peter received a vision commanding him to declare all types of food pure, and Agabus and his daughters in the New Testament would prophesy habitually. In the Catholic […]