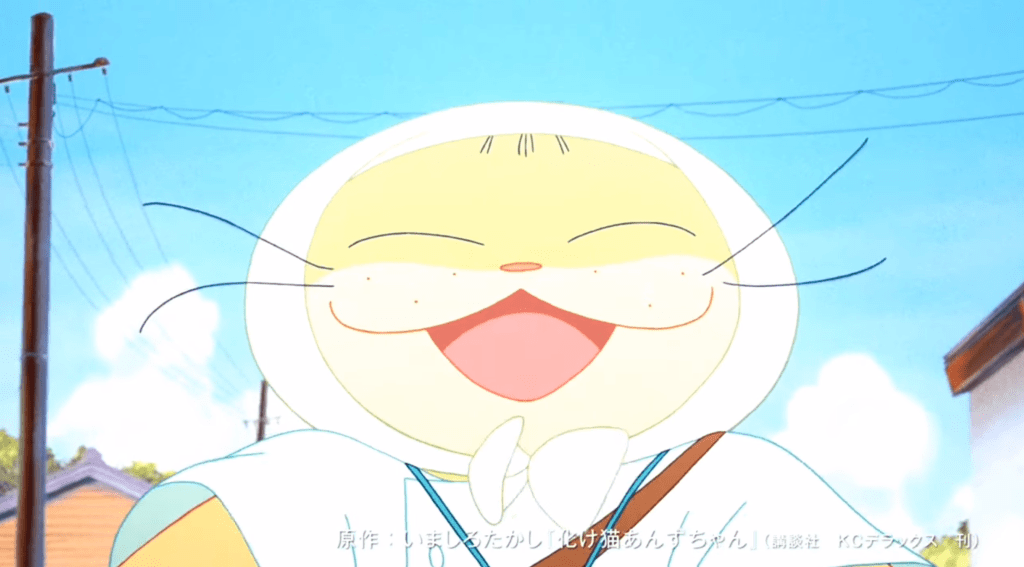

It’s a well-known fact that orange cats are…special. But temple cat Anzu-chan may just be the most special orange of all: he’s 37 years old, close to six feet tall, and rides a motorbike like a speed demon. He can talk too, but not well enough to get himself out of paying a fine when he’s pulled over for driving without a license. Anzu wasn’t always like this. He was once a normal cat, but as time passed, he crossed the boundary between the material and spiritual worlds at some point and transformed into a bakeneko or ghost cat. Now he spends his time running errands and doing odd jobs when he’s not lazing about or laughing at his own fart jokes. He may be anthropomorphized, but he’s still an orange.

All of this catches elementary schooler Karin rather off guard when she first arrives at the temple. She’s there to stay for awhile with her grandfather, the temple priest, while her ne’er-do-well father, Tetsuya, tries to get the loan sharks off his back. When his attempts to wheedle some cash out of his father produce nothing (apart from raised blood pressure for the elderly priest), Tetsuya bids adieu with the promise to return for Karin in time for their annual pilgrimage to her mother’s grave.

Karin is her father’s daughter and soon charms the local boys and Anzu’s ragtag band of kami friends, wrapping them around her finger. The ghost cat himself is more skeptical, eyeing both her peaches and cream routine and pitiable orphan shtick with insouciance. The two keep their distance. But when Tetsuya is nowhere to be found as the sorrowful day approaches, all that may be about to change. Or not. Cats can be fickle, after all.

The heart of Ghost Cat Anzu lies in the relationship between Anzu and Karin—a feature unique to the film adaptation of Takashi Imashiro’s slice of life manga, as Karin was created by director Yoko Kuno. Part teenaged brother to younger sister, part spoiled house cat to backup human, their dynamic provides much of the humor of the film, as well as its tension. Both characters are more than meets the eye: beneath Karin’s wiliness lies an unexpected generosity, particularly with her hard-wrangled money, while her short temper covers the loneliness of a young girl who just wants to see her mom again, even if only her grave marker. For his part, Anzu sheds his self-indulgence the moment his friends are under threat, showing surprising courage. The question of whether or not each will see the other on this deeper level is what makes the story so compelling.

It is also an intriguing work of syncretism, blending Buddhism and Shintoism with folklore and even urban legend. The diverse references build from a gentle stream in the first half of the story, to a virtual explosion of fantastical elements in the second that is sure to delight any enthusiast of Japanese culture. For others, it makes for a trippy ride!

But it is the look of Ghost Cat Anzu that makes it truly memorable. Much like Anzu himself, this film bridges worlds, bringing together Japanese and French animation in a co-production between anime powerhouse Shin-Ei Animation, which oversaw the storyboards and animation, and auteur studio Miyu Productions, responsible for the color design and background art. The result is magical, with lighting and hues that make the entire film glow with the radiance of golden hour. The color design is textured like watercolor paper, akin to Do It Yourself, but using a richer, deeper palette common in French animation and reminiscent of post-impressionist painters like Gaugin and Van Gogh, though the backgrounds are more impressionist in style. It’s a beautiful merging of animation traditions that I hope we see more of in the future.

The film also plays at the boundary between two other worlds: live action and animation. Ghost Cat Anzu actually has two directors: Yoko Kuno, who directed the animation, and Nobuhiro Yamashita, who directed the live-action version of the story that served as the raw material for the rotoscopy process pioneered by Kuno. This is rotoscope animation like you’ve never seen before. Unlike most rotoscoped films, where the forms and linework dance and shake in a way that can incite motion sickness in sensitive viewers, Ghost Cat Anzu has the smooth feel of freely hand-drawn animation, while capturing the distinctive movements and micro-expressiveness of live action. (To get technical for a moment, the difference is partly that Ghost Cat Anzu is animated on the 2s and 3s, like standard anime, as opposed to the 1s, as is the norm for rotoscopy.) The best of both worlds—and of both directors—comes together here to create a unique work of animation.

Both in terms of the story and the animation, Ghost Cat Anzu is a film that rewards rewatching. If this is the future of rotoscope, international anime collaborations, and Kuno’s career in feature direction, then the future is bright indeed. One might even say golden.

Ghost Cat Anzu is screening in Japan only, but it will open in France on 21 August, and hopefully internationally soon after that. It premiered at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival in June.

Images taken from the official trailer and Miyu Productions‘ website.

- Miracles from the Gutter, Turkey ep. 12 - 12.03.2025

- The Grace of Turkey: A Bowling Girls’ Gospel - 11.26.2025

- Review: Riviere & the Land of Prayer, Vol. 3 (Light Novel) - 11.20.2025

[…] previous years, I simply wrote up reviews of some of the films I was able to see and posted them as the movies received international release throughout the year. […]