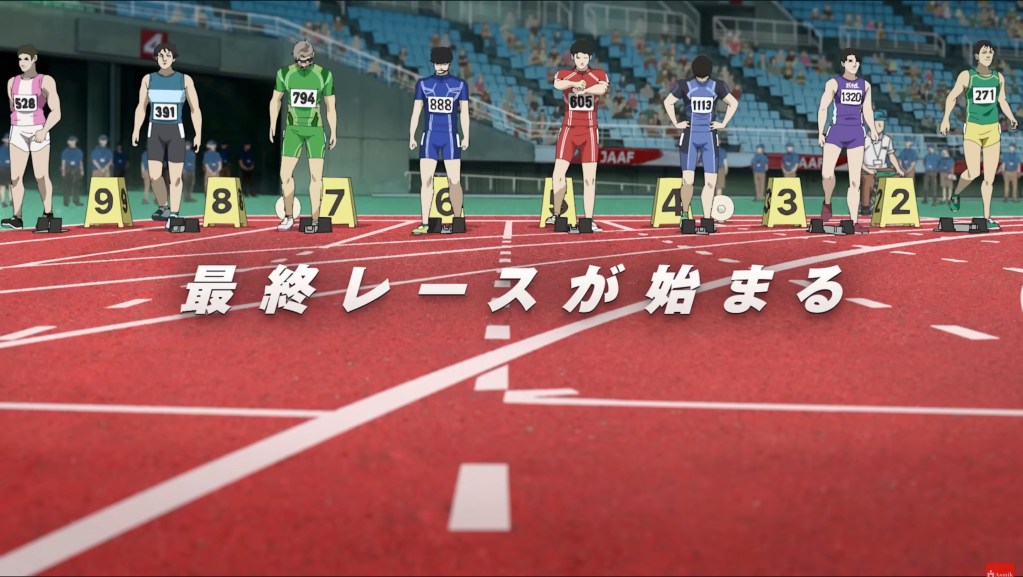

The 100-meter dash may be the most prestigious competition in modern athletics, but can such a short, straight race really make for engaging animation? This was the question driving director Kenji Iwaisawa as he approached this ambitious adaptation of the popular five-volume web manga by Uoto, Hyakuemu. Iwaisawa’s solution, he explained at the film’s world premiere in Annecy in June, was to develop the internal conflict, the emotional impact of the hundred meters. Yet, as the film attests, the medium of animation itself—with its riveting range of visual techniques—is just as powerful a means of captivating viewer attention, and ultimately, it is 100 Meters’ artistic accomplishments, rather than the emotional depth of its storytelling, that carry the film.

Togashi was born fast. Unrivalled in his speed, he has always dominated school track events, but the hundred meters holds pride of place in his heart. His athletic prowess hasn’t gone to his head too much, though, so when he comes across the new transfer student, Komiya, wheezing his way through a decidedly sluggish dash, he offers to help the boy improve his technique and grow strong enough to race properly. Judging by Komiya’s timid demeanor and dishevelled appearance, Togashi’s offer may be the first kindness that he’s ever received. Friendship blossoms—but not without its tensions, as Komiya proves to be a quicker study than Togashi anticipated. Then one day, a race does not end well, and the next day, Komiya is gone. Will the two cross paths again? And if they do, will they run together, or forever run their separate ways?

The setup may sound familiar to the seasoned viewer of sports anime, but 100 Meters successfully resists the predictable Mozart versus Salieri—or talent versus training—dichotomy (and indeed, fallacy, imho) to which so many tales of competitive performance succumb. Instead, it explores the diversity of ways of running, in all their strengths and weaknesses, telling a story that bridges the energy and enthusiasm of coming-of-age with the unexpected challenges and disappointments of early adulthood, in a way that is reminiscent of Oshiyama’s stellar Look Back.

The first part of the film, concentrating on the coming-of-age plot, does a good job of laying the foundation for an emotional payout later, when the two boys inevitably reunite. The contrast in their personalities and the unexpected synergy they find together are captured well through standout character designs (by Keisuke Kojima) and movement, while the seeds of misunderstanding in the way they part are planted subtly, leaving considerable ambiguity as to whether or not grudges have been conceived. There are also the indications of a tragic backstory for the loner Komiya that conjure up a question mark to loom over his future like the sword of Damocles. But following a time skip, which sees the boys cross paths again as semi-professional athletes in their twenties, the anticipated emotional payout never quite comes.

The missing payout is mainly a function of the writing, which doggedly keeps the story within the bounds of the track. This brings us back to the challenge of the ten-second timeframe of this sporting event. By necessity, much of the drama in so quick a competition must come from beyond the race, if not the track, too, as the races become symbolic of the larger drama unfolding in the runners’ life stories—lightning fast contests against self and others; waypoints charting an epic character arc. This is where the final part of 100 Meters comes up a bit short, as it provides only the barest peek into the lives of the cast outside of racing, while tantalizing hints of hardships faced and overcome remain unexplored. This is particularly disappointing when it comes to Komiya. Granted, the task of condensing five volumes of manga into 100 minutes—when the average 13-episode series covers four volumes and clocks in at three times that duration—meant that much had to be sacrificed to the cutting room floor (and indeed, much may also have been absent from the source material itself), but the profusion of new characters introduced after the time skip likewise dilutes the narrative focus.

In the final leg, rather than emotional showdowns, the races become more a forum for the philosophical sparring of the runners, whose dialogue is weighed down with inscrutable pontification. Part of the problem here is the absence of any context—in the form of glimpses into personal lives and experiences—to anchor these philosophies and aid audiences in interpreting their significance. As a result, the latter part plods along a bit flat-footed. That said, in true sports anime fashion, the final scene saves the day, drawing together the threads woven in the first part of the film just enough to bring a satisfying resolution, as a sudden burst of joyous emotion upends all the ponderous theorizing of the adult athletes with the freedom and glee of a child kicking over a sandcastle.

While the narrative may wobble in the final stretch, the animation impresses throughout, right up to that glorious final shot. 100 Meters showcases the creativity and innovation that is possible through the rare combination of independent and professional studio (namely, Asmik Ace) approaches to animation, applying every tool in the traditional 2D toolbox to ensure that a short, straight race on repeat remains engaging, dynamic, and occasionally, downright spectacular. The linework often takes on a rough, hectic quality. At times, the animation and background art imitate other artistic mediums, including Greek pottery, watercolor painting, pencil crayons, and pastels. At others, it is the cinematography that adds freshness to a race, such as one pivotal competition where the camera tilts up and fixes on the sky above the blocks, leaving the race to play out sonically, rather than visually, conveying both the intensity and brevity of this high-stakes sport. Not every technique lands completely—there are some instances of visuals that verge on photobash—but the energy that such experimentation with style and form brings to the screen is engrossing, placing 100 Meters alongside recent artistically pioneering series such as Mob Psycho 100 and Bocchi the Rock.

The foundation of the animation, however, is rotoscopy. Similar to Yoko Kuno’s Ghost Cat Anzu, live action filming was used as reference for 100 Meters, rather than as a strict blueprint for the movement. Iwaisawa and Animation Director Keisuke Kojima went through the footage painstakingly, selecting ten or twelve frames out of twenty-four per second to use as reference. Although the actors were cast for their resemblance to the manga character designs, they were modified during animation, reducing the size of their heads to create a more athletic build. The result is rotoscopy that avoids the pitfalls of quivering contours and queasy micromovements, while enabling sweeping, highly mobile long-takes without the use of CG. It’s a delight to see rotoscopy used so effectively, and speaks well to the future of the method, under directors like Iwaisawa and Kuno!

The use of rotoscopy and the particular method developed for this production also facilitated the recruitment and training of a significant proportion of young animators, fresh out of art school. (In fact, at the film’s Works-in-Progress session at Annecy in 2024, the panel even made an open call for new graduates to get in touch—only half-jokingly!) This meant that Kojima had his hands full with Key Animation corrections, but also that, going forward, 100 Meters will boast a special legacy as the project upon which many up-and-coming animators of the next generation cut their teeth, or rather, sharpened their pencils—making Iwaisawa and Kojima rather like Togashi, helping others improve their technique so they too can “compete” on the world stage of animation.

100 Meters is Kenji Iwaisawa’s sophomore run as a feature film director, following 2020’s indie darling, On-Gaku: Our Sound. It shows just as much artistic courage as his inaugural title, considerable growth in execution, and even greater promise for what is yet to come! It also displays a welcome increase in production speed, meaning that hopefully, we will be treated to his next feature, Hina, sooner rather than later.

100 Meters will be available on Netflix from 31 December, 2025.

Props to the Annecy International Animation Film Festival for hosting the Work-in-Progress session in June 2024, and premiere of the film in June 2025, making this review possible!

- Film Review: All You Need Is Kill - 01.15.2026

- First Impression: Kaya-chan isn’t Scary - 01.11.2026

- First Impression: Dead Account - 01.10.2026