Before Evangelion, there was Gundam. In the 1970s and the 1980s, the memories of the Second World War were still fresh, and the Cold War turning blazing hot was a close, frightening prospect. Time travelers were finding the ruins of our civilization buried in the ground. Akira saw Tokyo rebuilt around a giant crater. Even Dr. Seuss was doing “any day now” stories.

It was at that time that Yoshiyuki Tomino started telling the tale of a weapons race that leads to the outbreak of hostilities between Earthmen and Space colonizers. Unexpectedly, this puts a young boy aboard the ultimate weapon, a knightly robot that brings him and his people both hope and despair.

This is a concept that has proved its endurance, becoming one of the staples of the mecha genre. I approached this series after being blown away by the beautiful and tragic Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket. Would Gundam 0079 hold up after almost half a century? The answer is yes. While the story of Amuro Ray cannot by its nature be as airtight as that six-episode special, it still has heart, a legion of interesting characters, and something to say about war.

But what, exactly, does Gundam have to say? Is this war noble? Is this war absurd? Is Amuro a hero? Is he a tragic figure, robbed of his childhood? The answer is quite nuanced, and brought to my mind a mysterious—even paradoxical—saying of Christ: “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34).

What is the Prince of Peace saying here? The path of the Gundam pilot is a paradoxical one, a path that leads us to hold both war and peace in our hearts. This is pretty much the path of a Christian in this world too. For on the one hand, we are called to love our enemies, returning evil with good (Matthew 5: 38-48), yet on the other hand, swords are very present in our lives (Matthew 10:34, Luke 22:36). Here we go!

Gundam and Amuro: Rage On, but Don’t Forget

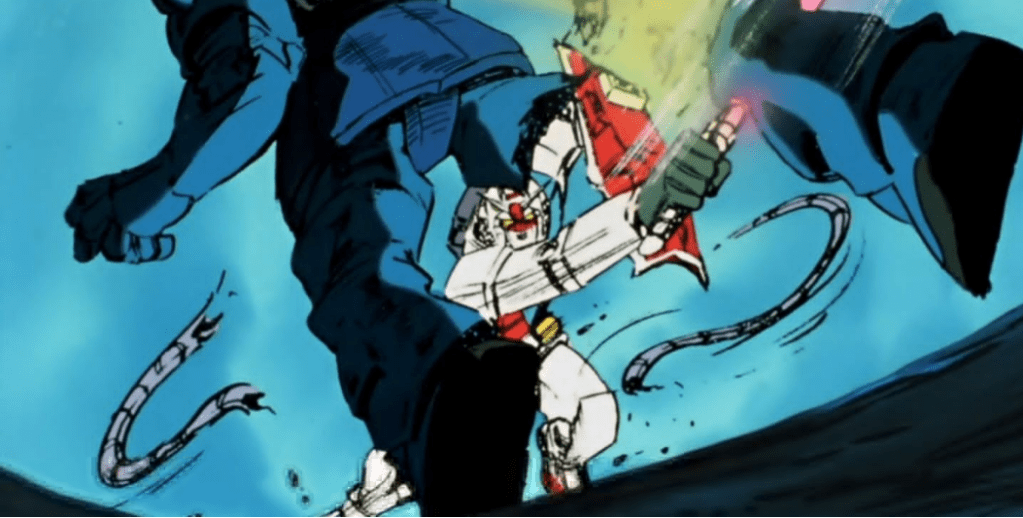

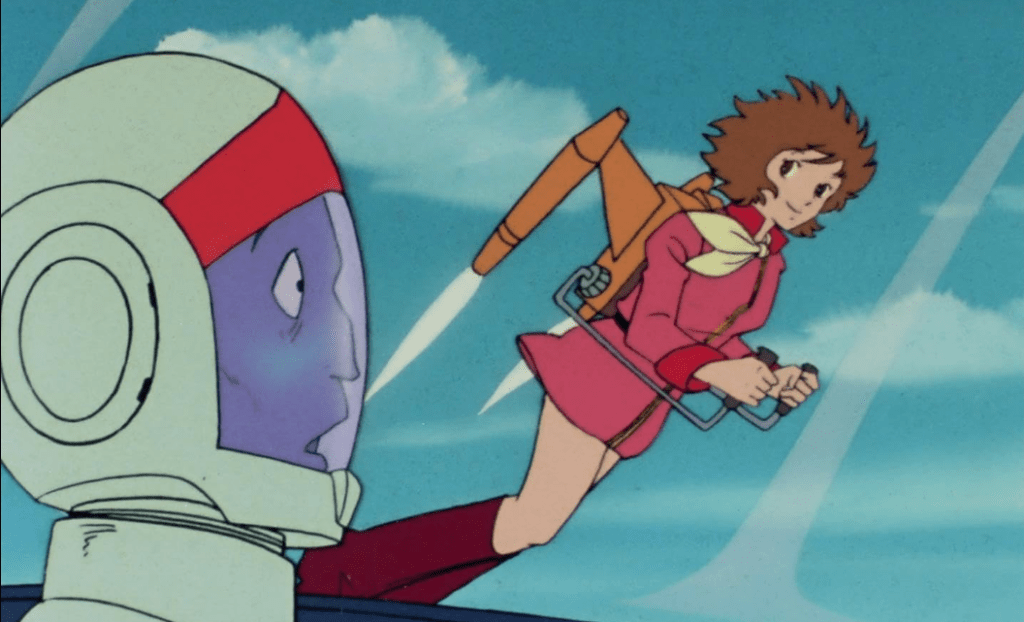

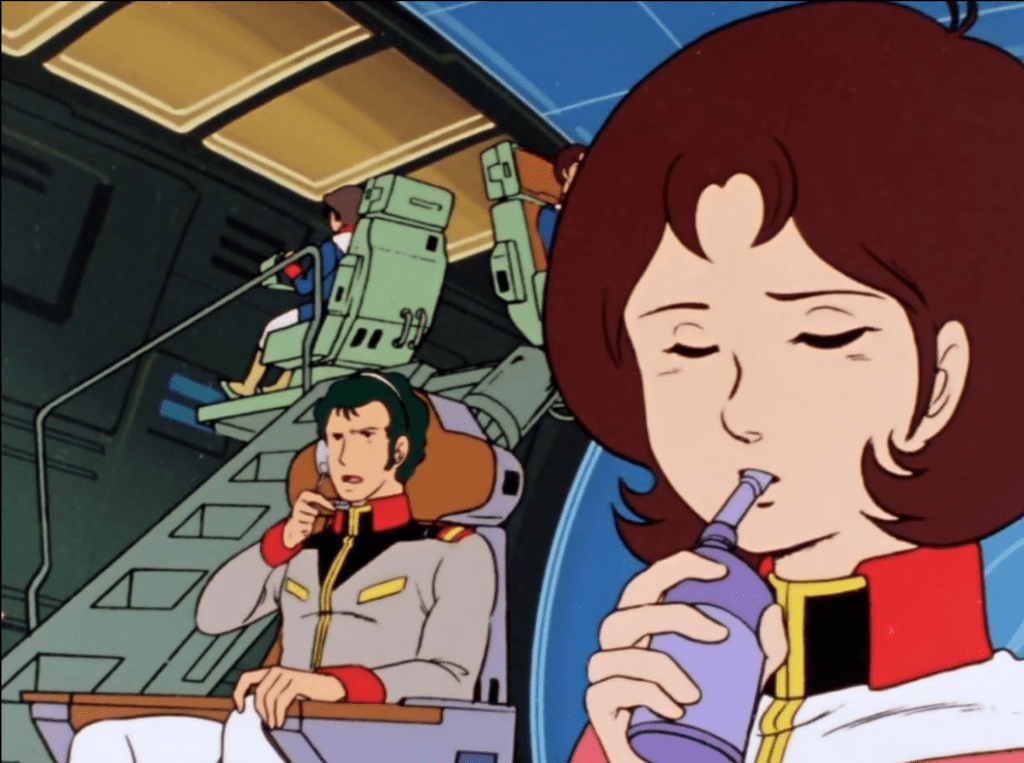

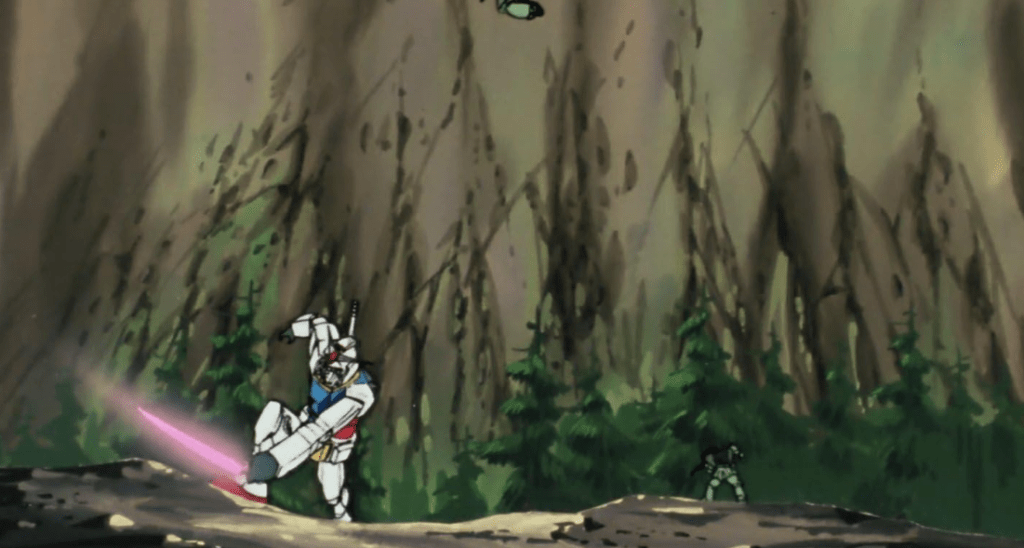

The first frame of the first Gundam show ever is an image of the Earth seen from space. A light, perhaps an explosion, appears on the right side. “Rage on, Gundam!” shouts the opening, and the samurai robot appears. The choir feels a bit off-putting for my 2020s ear. The synth, on the other hand, is glorious. Part jet, part armored giant, wielding a gun and a lightsaber of sorts, the shots of the robot are intercut with the face of a young boy and those of his friends, dressed in colorful military uniforms.

Amid PowerPoint-style titles and amazing seventies hairstyles, a great number of enemy robots appear. Our heroes turn and extend their hands, reaching for the sun, for the light above. Snippets of spaceships, space cities, and the Gundam in action culminate in it jumping at us. Everything is bright, everything is triumphant.

The contrast with the melancholic song we hear at the end of each episode could not be greater: “Amuro, don’t look back / The glowing star at the end of the universe /Is the birthplace you abandoned, Amuro. / Don’t forget! The vows from the days of youth / Draw on your youth and protect this happiness,” the singer gently pleads.

With these words, the Earth becomes Amuro’s eye, and we start to zoom out. We see his destroyed space hometown, the young man scowling and looking over his shoulder, and lastly, the smiling crew. Behind them, the Earth rises again.

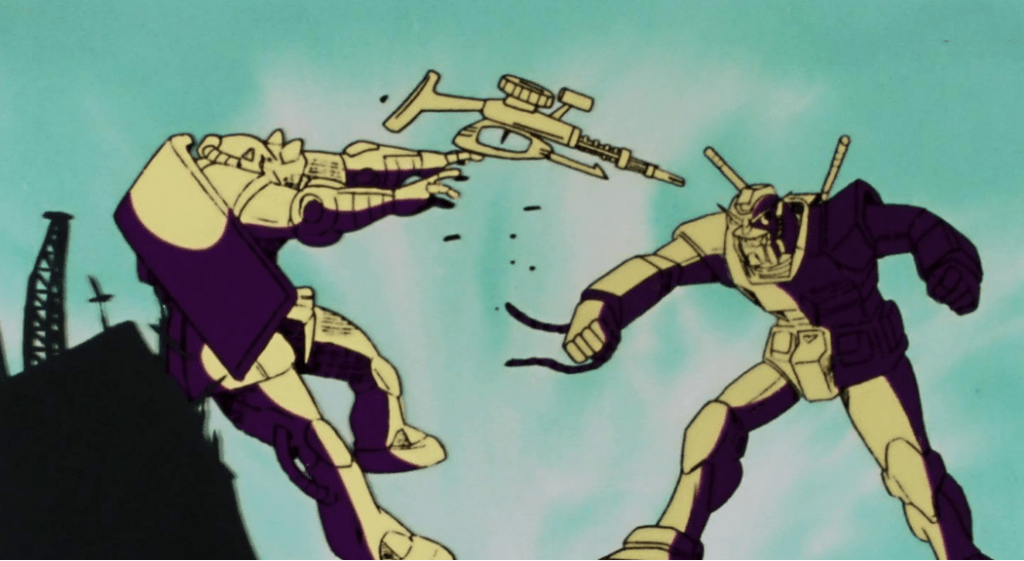

These are the two moods of the show: the glorious and the somber. We constantly see how easily this big conflict could have been avoided. We become aware of how the enemy is just like us. The toll on every member of the cast is immense and portrayed with unusual realism. Yet, at the same time, we see Amuro’s knightly quest to mature and become a self-sacrificial hero, one who might even be able to help humanity as a whole.

Some read this as an anti-war show contradicting itself. “War is terrible, don’t do it. It is also formative and epic, though!” I don’t think this quite captures the beautiful paradox of Gundam 0079. Amid these heartbreaking, beautiful battles, we get to see how it feels to grow up as the world is raging around you, to face the complex, sometimes infuriating dilemmas of the adult world.

This year, for one reason or another, I have read about a lot of wars. Persia and Greece, Athens and Sparta, Octavian and Mark Anthony. Sometimes, the writers themselves were witnesses to these conflicts. The horrors of aggression and the compassion for the victims are side by side with the sacrificial love in extreme situations, the moral courage which is often put to the test, and the questions which arise when one faces the ultimate risk.

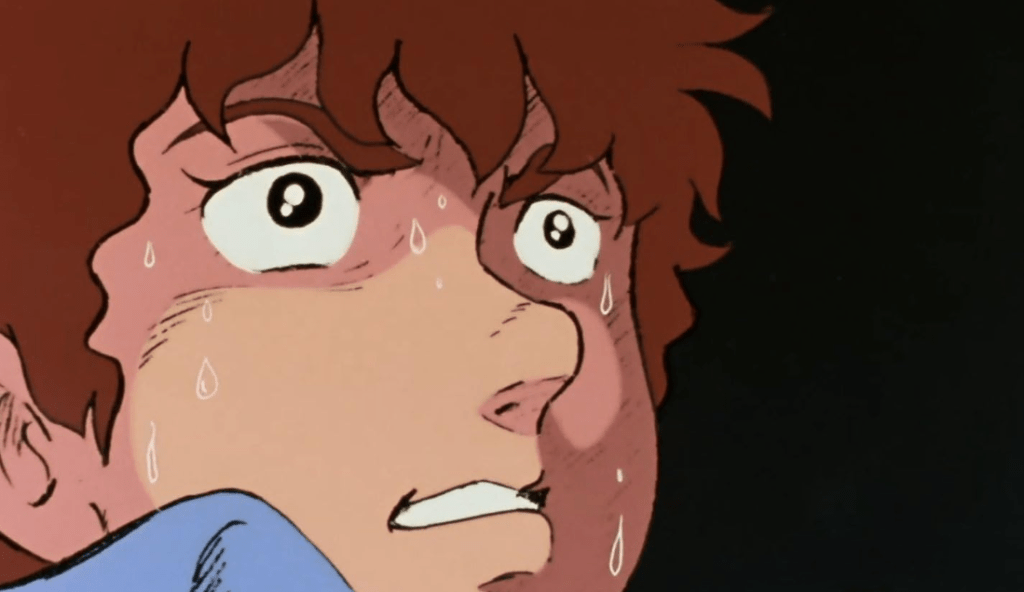

Gundam 0079 rings true in precisely this way. When “the boy,” Amuro Ray, (spoilers ahead) finds his mother in a refugee camp, she does not accept him. She sees a ruthless soldier, and finds his actions disturbing. “I didn’t raise you to be like this! You were such a sweet little boy! Go back to the way you were!” she shouts. But Amuro knows that there is no way back. He has changed too much. He has comrades. He is fighting for a cause. And yet…

And yet, his father, a scientist working in the arms race, doesn’t provide him with much guidance either. When Amuro finds him, he is lost in the war effort, barely sane—he has become a cog in the war machine, like the person Amuro’s Machiavellian commanding officers often try to make him into. This life of fear unto death, lost comrades, and discipline beyond his years cannot be the foundation of his identity either.

Heartbreak after heartbreak, Amuro’s attempts to either escape or conform turn out to be misguided and do not offer the intended results. Trying to ignore the whole thing and go back to his pre-war life does not work. He has simply changed too much. Taking pride in his unique military value makes him miserable. But Amuro is not alone in this war. It is his fellow crew members who are able to see the real Amuro and become a support system for him, a community. And in that community, he finds peace.

Gundam 0079, thus, is a war story that speaks beautifully about the kind of loving connection that is the foundation of peace, and the motivation to take great risks to keep others from harm. Coming back to the opening and ending themes, we see that they spell out the solution to the paradox: The memories of love are, for Amuro and Amuro’s comrades, a vision of peace that prompts them to fight through the conflict to a new tomorrow.

It is the love of peace, and the hope it carries within itself, that ultimately allow these warriors to fight for peace without losing themselves, and which permit the gigantic sci-fi samurai and the boy with growing pains to be one and the same.

The Messiah: Peace and the Sword

Centuries before the Messiah was born, the prophet Micah foretold that he would be called “our peace” (Micah 5:5), or “Prince of Peace,” as Isaiah puts it (Isaiah 9:6-7). Zechariah expands upon this (Zechariah 9:10): Jesus is the peace of the world, the end of all wars. The bow of war will be broken, and then He will proclaim peace to the nations. When He is born, the angels sing, “Glory to God in the highest; and on earth, peace to men of good will!”

Though the contemporaries of Jesus expected for the Messiah to be the leader of an insurrection against the Romans, presumably hoping that the prophesied peace would come after this final victory, Jesus made a point to lead a revolution of the spirit, not the sword: to fight not the Empire, but darkness and sin. Ultimately, He walked to his Passion voluntarily, even if He could have brought his persecutors to the ground with a word.

This first coming of Jesus, though, was not the end to all wars. “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. I do not give to you as the world gives,” He tells his Apostles after the Resurrection. “Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid.” Jesus promises us peace, but it is a different kind of peace that not only coexists with the sword—it brings it!

We now come to the end of the chase. As Jesus is instructing His disciples to go and preach in His name around Galilee, He tells them, “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; and one’s foes will be members of one’s own household” (Matthew 10: 34-36).

This is, indeed, the kind of struggle that Amuro faces: the hostility of those he is trying to get answers for in a troubled time. What Jesus is telling His disciples—all of us throughout history—is this: Just as the invention of the Gundam robot breaks the fragile peace, bringing about the conflict between Zeon and the Earth, Jesus brings a revolutionary principle to the world of man. He brings to every individual life an invitation to close contact with God Himself.

St. John the Evangelist vividly depicts this “escalation”: “The light has come into the world, and people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil. For all who do evil hate the light and do not come to the light, so that their deeds may not be exposed. But those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God” (John 3:19).

What Jesus offers does not threaten the temporal position of, say, Emperor Tiberius or King Herod. Yet God interacting directly with each of us to bring salvation produces a moral upheaval, a revision of the hierarchy of priorities of every individual and collective human endeavor. It is also a direct threat to the power of tempting spirits, of demons. As such, it will always generate resistance and conflict, so strong that even those who are closest to the disciples of Jesus may become aggressors.

This happens in all the ages of the history of Christianity. Be it the Roman Empire, the Japanese Shogunate, the French Revolution, or the Soviet Union, regimes of all nations suddenly decide that their Christian citizens are an ideological threat. Once, Pope St. John Paul II asked a seminarian for the “four notes” of the Church. The seminarian gave the classical Catholic response: “One, Saintly, Catholic, Apostolic.” The Pope asked for more, leaving the young man confused. “And persecuted,” the pope concluded.

Throughout the eras, we see this come to pass again and again. In that way, even as lovers of peace, our life is warfare (Job 7:1)—our spiritual warfare against sin, and often also physical warfare that we are subjected to in the form of hatred, threats, and violence from people who feel our faith is threatening to other principles or bonds. Jesus brings us the sword, but He also illustrates in His Passion and Resurrection that it doesn’t have the last word.

The Full Armor of God: The Spiritual Battle

So how does Amuro walk this path of war and peace? And what about the Christian? The first thing to keep in mind is that, even as they face war, they learn to love peace in big and small ways. Christ loves peace, calls for radical love, and blesses the peacemakers—a role Mirai’s father has in Gundam 0079. Both our characters and the disciples of Christ learn to consider the enemy as a sibling, and point their fighting efforts against the spiritual causes of enmity.

Our characters are soldiers. St. John the Baptist told soldiers not to oppress or steal, but he didn’t tell them to pick another line of work (Luke 3:10-14). Centurions and legionnaires were among the early Christian converts and martyrs. St. Paul reminds us that the earthly authorities legitimately bear the sword against wrongdoers (Romans 13: 3-5). In the fallen world, the human community needs defending, and the disciples of Christ are still its citizens, so they may be a part of that effort, be it as security guards or as mecha pilots.

But Christians may not fight with hate in their hearts, nor repay evil with evil. This difference is key. Because the deepest war is beyond any physical struggle. It is a war against evil, against sin, which is the deeper cause of human violence. Instead of fighting against bodily enemies, we strike at the cause inside of us in the spiritual realm, thus rescuing what is good in us, so we can help others get rid of it too (Matthew 7:5).

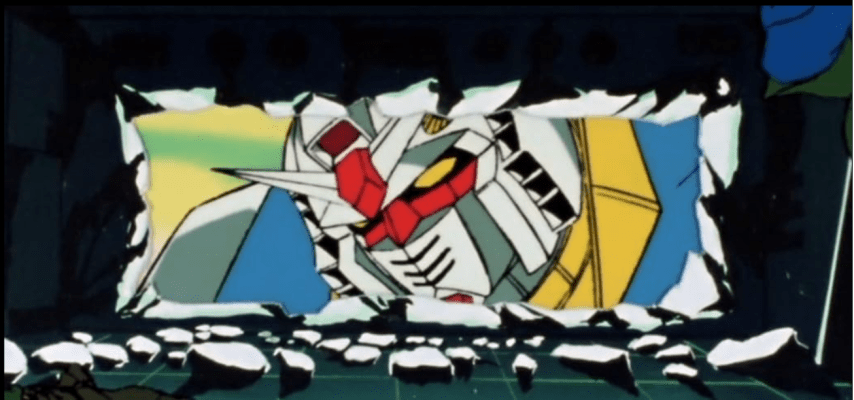

Amuro’s biggest fight was always against himself. In front of our eyes, the selfish, bratty, inconsiderate kid learns to be a friend, a brother, a protector. And, ultimately, his fight transcends the visible: As one of Humanity’s first “Newtypes” who can see the future and communicate by telepathy, he overcomes hate, creating bridges that are spiritual rather than physical and that end up saving the little family he has found.

In Gundam 0079, this is the conflict beneath the conflict, and one that has theological undertones: There are hints that the characters are evolving, and that the White Base is an Ark of Noah of sorts: Amuro sounds like “amour,” or love; “Mirai” means “future”; “Sayla” sounds like “sailor”; “Noah Bright” is the captain of the ship; and “Fraw Bow” recalls the rainbow that culminates the story of the Ark, marking the alliance between God and Noah, and through the latter, all humanity.

Amuro is growing along this unsuspected path, one of love for everyone. His experience in the Gundam is meaningful for all. Christ also arms us with a complete armor for an invisible fight, one greater than any other—one fully compatible with His love of peace, so great that He voluntarily goes to His Passion. The way St. Paul puts it (Ephesians 6:10-20) will delight any Gundam fan.

Paul reminds us (Ephesians 6:12-13) that “our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against […] the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. Therefore take up the whole armor of God, so that you may be able to withstand on that evil day, and having done everything, to stand firm.”

Like the Gundam, the armor has many pieces: “Stand therefore, and fasten the belt of truth around your waist, and put on the breastplate of righteousness. As shoes for your feet put on whatever will make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace. With all of these, take the shield of faith, with which you will be able to quench all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.”

The way of the Church—the way of daily prayer, of the interior struggle against sin with the aid of grace, of connection and love, of the steadfast announcement of the Gospel—is the greatest of epics. Just as we marvel at our young soldiers and their journey, we will learn to admire the feats done in a war that is spiritual, though it might turn physical in the form of persecution.

If that happens, Christ reminds us that we might need to accept a sacrifice not unlike Amuro’s, and find our deepest identity, to love with our deepest love, to put our deepest loyalty in God rather than riches (Matthew 19:16–30), recognition (Matthew 6:1), friends and rulers (Psalm 146:3), and even our own families (Matthew 10:37). This is Christ’s famous “hard saying,” which He puts in the most striking terms, to show us just how it feels.

It would be humanly impossible to win in this battle, if not for Christ giving us His grace and His peace to remain steadfast as the war escalates around us. And so we live in battle, yet fight for peace. We wield the sword, not to start a cycle of violence, but to transcend it in Christ. We participate in earthly conflicts when we must, but we only hate evil and not other people.

Or that is the goal, anyway. In Gundam, the interactions between Newtypes and the solidarity and direct connection they develop make us hope for a future of peace, but Char Aznable rejects this idea again and again, choosing to play his personal games. We’re still sinners. The Church sometimes provides us with signs of hope for Heaven, but the example of the Apostles themselves shows us how the worldly conflicts and rivalries still sneak in. Still, we persevere.

And we have hope, because our king is fighting with us. It is when Amuro has matured and been pierced by Char’s sword that he is able to see everyone, call them, and rescue them. We may think here of Christ, who, pierced by the sting of evil but awake and alive, calls us from across the distance, talks to us, directs us, leads us to salvation. Now it is not in the physical White Base, the Ark of Noah, but in the Church and the new connection established through Him.

Let’s meet at the other side of the war, y’all. When the prophecy comes to pass, when peace comes. And until then, may God help you in your fight!

Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) can be streamed on Crunchyroll.

- To Be Hero X: Of Exaltation and Sorrows - 11.12.2025

- First Impression: One Punch Man Season 3 - 10.13.2025

- First Impression: Chitose Is in the Ramune Bottle - 10.07.2025

This was a lovely, insightful reading of one of the most significant classic anime series of all time. I had never considered Amuro’s journey through the lens of a Christian’s struggle through our fallen world.

The Gundam, however, did not “break the fragile peace, bringing about the conflict between Zeon and the Earth.” The war had been raging for nine months (a significant period of time since it corresponds to the normal term of a pregnancy) by the time the Gundam takes its first steps. In that sense, Gundam 0079 is very realistic about the state of human nature: conflict is present even when we don’t see it in our day-to-day lives. Anyone could be called upon to take a stand against evil, whether or not they think themselves worthy or prepared, or even if they don’t want to take up that responsibility.

In this way, I’m reminded of 1 Peter 3:15: “always be prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks for the hope that is within you.”

Thank you for the comment, and for the precision! That’s a beautiful reflection.

To add to the previous post, the backdrop to Mobile Suit Gundam was that the Principality of Zeon, a group of colonies farthest from the Earth declared independence and massacred people and did a colony drop onto Earth; their intended target was Jaburo, in South America, but the Federation fought back and so the colony missed its mark, and instead hit Australia. Zeon were never the good guys, but the epitome of Hitler and his regime (in fact, Gihren Zabi’s father, Degwin, says specifically he’s following Hitler’s footsteps).

Gundam’s rich geopolitical tapestry is one of the reasons that make it seem so real. Thank you!