In the age of The Matrix Resurrections and The Rise of Skywalker, sequel disappointment is like the common cold. Continuations of great stories must attempt to walk the tightrope of making us feel the magic once again while avoiding treading the same ground. Many try, a few succeed; most are mercifully forgotten, but some even bring the original down with them. And has an anime ever reached such heights and then fallen so low as The Promised Neverland?

Season 2 is bad; I can picture Ray’s expression watching it. As thathilomgirl pointed out at the time: From the time jump, the train runs faster and faster, then goes off the rails, then crashes and burns. No matter. The twelve original episodes, plus the first four of the second season, are my favorite anime to this day. In my rewatch, I stop at Shelter B06-32, then take a deep breath. These sixteen episodes never fail to light my heart ablaze.

The manga is a good read, but it’s just not the same. In the anime rewatch though, I may not be astonished like the first time, but the power remains. This has to do with TPN’s brilliant structure: The pace, the highs and lows, the concepts, and how it speaks directly to my inner world. As I watch, I have come to realize that the structure also resembles the order of the Holy Mass, the cornerstone of my week and my life of faith. And I know that this is a bold statement, but I don’t think this is accidental. Am I crazy? Well, it’s all in the name.

What’s in a name?

A group of orphans living in a Victorian manor discover (spoiler warning!) that they are being raised as cattle, and that their caretakers are their enemies. Outside the orphanage, beings called “demons” (oni) wait to consume their flesh and especially their brains. Theirs is a five-star human farm whose products are consumed by demon royalty. But there is another kind of demon out there, and their messiah is called Mujika.

Before the first image pops up on the screen, TPN refers us to two iconic stories: JM Barrie’s Peter Pan and Wendy, and the Bible. The Promised Land is Canaan, which God grants to Abraham and leads Moses to, and Neverland is the island of eternal childhood where Peter Pan lives. All the kids in the world must grow up, but TPN gives us a twist: They might be swallowed literally or figuratively by a dark, predatory world. Against this threat, there is one hope: to walk according to the promise and find the promised place.

You can easily see the independently minded shadow of Peter Pan wandering all around this story. Let me count the ways: Two boys and a girl, nanny uniforms, a gang of lost warrior-boys, a life in the wild, the possibility of never growing up, the focus on the mother-children relationship, and a shelter. If you still hold any doubt, well, it can be no coincidence that the Ratri brothers, the two brothers who are at odds over the children, are named Peter and James, like Peter Pan and his nemesis Captain James Hook, while their servant goes by Smee, like the bespectacled Irish pirate from Barrie’s tale.

There are influences from other folktales too: The demons are like the child-eating, shape-shifting ogres from Jack and the Beanstalk, Tom Thumb, or Puss in Boots, adapted into beings that absorb the characteristics of what they eat, including intelligence. But they are also “demons.” And the fight between corruption and the light has distinctly Christian undertones. We have our Ratri moments too: The “old faith” the demons know of is clearly inspired by another old faith, Christianity.

So far, I have kept things vague, but this is your spoiler warning. Beneath TPN’s “demon world,” there is a half-forgotten structure resembling things we know. Forgotten temples where food offerings are made and where wall murals depict a foundational covenant. Sacrifices of the heart, and groups that deem some kinds of foods impure. A ritual and a feast day involving a banquet. Dissenters known as “heathens,” a cup of blood, and a promise of salvation.

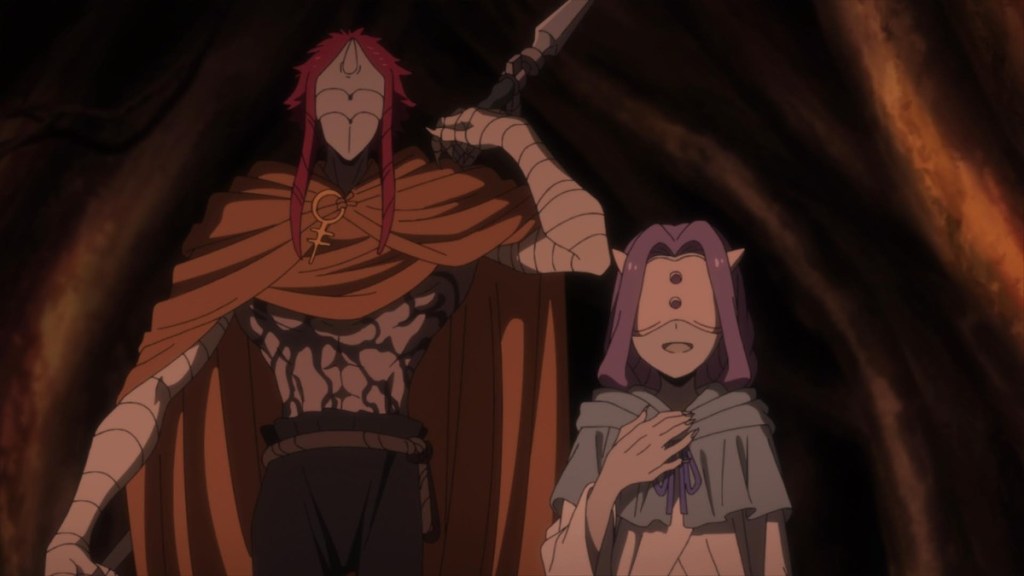

As our characters leave slavery and walk towards the promise, more Christian concepts begin to emerge. Many of them focus on Mujika, an ogre-demon mirror of Emma, as another girl who keeps a pure, loving heart in a world of cruelty and hunger. She’s also a Messianic figure. Her followers abstain from human flesh for religious reasons. This means that both girls preserve the purity of the hearts of those who put their trust in them.

In the manga, we learn that Mujika (a Japanese name denoting “dream,” “poetry,” and “flower”) was actually born millennia ago. From birth, she possessed a power unique among her kind—that of not changing her form no matter what she ate. Thus, she didn’t need human flesh. Even more, those who drank even a drop of her blood, which she gave freely, became like her: freed from murder, from dependence, from darkness.

The Christian Connection

This sounds remarkably like the story of Jesus Christ, Our Lord. He, too, was born millennia ago without sin, unlike the rest of humans, and was thus preserved from corruption, both moral and, in time, also physical. He was raised in rural Galilee, followed by crowds and disciples, and ultimately gave his blood and his body on the Cross for the salvation of all. The day before He laid down his life, He offered a cup to his disciples, saying “This is my blood,” offering us a new kind of life.

The parallels extend to Mujika’s followers. As the news spread about the blood that makes you free from eating human flesh, the upper echelons of demon society were shaken. They were counting on their control of the human farms and delivering “goods” of varying quality as a tool for social dominance. And so the blood of Mujika was deemed the “evil blood,” her followers “heathens,” and persecution and dispersion ensued. The Roman Empire and the Sanhedrin didn’t take kindly to the new faith either.

Of course, there are big differences. TPN has a God figure, whose name cannot even be pronounced by human tongue, but this deity is indifferent rather than loving. Its foundational covenant is twisted, rather than good but unfulfilled. This means that a completely happy ending is out of the question. And yet, a striking parallel remains.

The remarkable thing is that, after millennia, Mujika lives. The mutation that freed her from the hunger of human flesh also made her immortal. She still wanders the world, offering her blood to those who wish to receive it. Likewise, I believe that as I write these lines, Jesus lives, walks, gestures, looks left or right, and talks, although He is hidden until we see Him again. Like Mujika, He still acts in this world, alive forever. And He still offers us His body and blood.

This mystery of death, resurrection, and eternal life is connected to His words and actions during the Last Supper, that last night before the Cross. And in turn, the idea of sacred banquets that bring life is central to the lore of TPN. Hence the connection; hence the parallels. The theme of sacrifice brought about by love for the sake of the salvation of many in a world of shadows, of being sacrificed by others versus sacrificing oneself for others like Christ did, drives the story.

At the beginning, I talked about disappointing movie sequels: The life of every Christian is, in a way, an unworthy sequel to the gospel, except that what made the original great is certainly still there in each of our lives—Jesus lives and continues acting in us. There is a continuity between the past, the present, the mysterious future, and what lies beyond time. Our spiritual life is an attempt to dive deep into that connection, into a story that is also our own, setting our hearts ablaze once more. But how?

The Greatest Story Ever Told

If you have watched TPN, you may have noticed that the part that inspires me in such an extraordinary way—that is, the first season—has none of the elements I just analyzed: They’re all introduced later. Nevertheless, just as Peter Pan is around long before Smee shows up, the Christian concepts also inform the first part of the story in a subtle, symbolic way, providing abundant parallels to Emma’s Christian-inspired sacrifice for the salvation of all who partake in it. A great story like TPN is constructed like a fractal image: Everything is connected.

As it happens, I like TPN’s foreshadowing more than the actual things being foreshadowed. It has unparalleled tension, focus, and resonance. Highlighted by the music, the color design, and a commanding pace that almost forces you to watch the next episode, it is a joy to experience. This is why I reflect upon my life as I watch these characters learn, struggle, lose, repent, and win—why, when the loving sacrifice and its outcome play out, my heart is filled with joy. It is this part that reminds me of the Holy Mass.

What is the connection with Mass? According to St. Thomas Aquinas, an old friend and revered teacher of mine (Summa Theologiae, III, q. 83, 4), the Holy Mass is a ritual prayer built around the Eucharist, the offering Jesus made of His body and blood in the Last Supper, anticipating His loving sacrifice on the Cross. Its aim is to lift our hearts, to gradually prepare our souls for communion, and to submerge us into the story of salvation so we can recognize Our Lord as the bread that is broken.

Illustration by Posuka Demizu, TPN, Chapter 176.

Like Mujika’s followers, many Christians have risked their lives to draw near the altar. In the year 304, amid Roman persecutions, a group of Christians living in a town named Abitinae in the Roman province of Africa attended the Holy Mass, disregarding the edict of the emperor and putting their lives at risk. When interrogated as to their reasons, they simply responded, “Sine Dominico non possumus.” Without the Sunday Eucharist, we cannot live.

Life and food are connected. The white flower that turns red is used by the demons in TPN to prevent the quick decomposition of the dead, but it is also, according to Mujika, part of an ancient thanksgiving ritual for the role food plays in preserving their lives. Emma learns to use her bow to kill and eat, but she adopts this ritual as well. She kills because she has to kill to live, but she does so in a spirit of gratitude and love. Meal and sacrifice, both in their uplifting and their horrifying versions, are at the heart of TPN.

These elements are at the center of the Holy Mass, too. The purpose of it all is that we may receive Christ’s sacrifice with understanding and love, and eat and drink the body and blood of Jesus in a way that brings us eternal life in the ultimate Promised Land. Because, as St. Paul reminds us, to eat the body of the Lord and drink His blood unworthily amounts to eating and drinking one’s own damnation (1 Cor 11:29). What is salutary in itself becomes poisonous to a poisoned heart.

Under the Surface

We have talked about the sources and inspirations of TPN. The Mass has a variety of sources, too. Among them are the more mysterious and symbolic events of the Gospels, the ancient liturgy of the Jewish Temple, the rite of the Passover meal, and the chants, Psalms, and celebrations of Israel we read of in the Bible. They all come together to celebrate the greatest love story ever told.

The main sources of the Mass, though, are twofold, the first being the sacrifices of the Temple, which began when God told Abraham to sacrifice a ram in the place of his son Isaac (Gn 22:13). From the beginning, the animal sacrifices were, in a mysterious way, made in place of the sacrifice of the Son. This is why, as the Epistle to the Hebrews says, with the coming of Christ, the animal sacrifices meant as a metaphor for it were abolished (Heb 10:10, 14, 18).

The sacrifices of the Temple were of three kinds: the burnt-offering, also known as a holocaust, in which everything was consumed by fire for God; the meal-offering or sacrifice of communion, in which the sacrificial meal was shared between God, the priest, and the people; and the grain offering, made of flour and oil (Lv 6:7-11). All three are present in the Mass, and the imagery of animal sacrifice is also part of what Mujika’s followers do after hunting.

The second inspiration for the Mass is the cup ritual of Passover. On the night of Passover, the people of Israel would come together with their families and bless the wine in honor of the holiday, sitting around the table like the kids of TPN. They still do so today, following a very similar ritual. Essentially, after pouring a second cup, participants wash their hands for purification, eat herbs with saltwater representing tears, break the bread, and retell once more the story of the first Passover, using as a template the “Four Questions” the youngest person in the room has to ask.

The rite continues as the celebrants wash their hands again, then eat bitter herbs and the lamb without defect, which was sacrificed that night at the Temple in Jerusalem. A third and a fourth cup are served, and one is set aside for the prophet Elijah, who is prophesied to herald the Messiah. After the singing of some chosen Psalms, the Hallel, the last cup, is lifted, blessed, and drunk. “I will lift up the cup of salvation and call on the name of the Lord” (Ps 116:13).

This is the memorial of the flight to the Promised Land. If you put together the accounts of the four Gospels, you can see Jesus celebrating his own Passover meal with the apostles the night before the Passion, with washing, singing, cups of wine, bread, and a new sacrifice. But now, He is in the place of the sacrificial lamb. His blood is the blood of the Covenant. This is the first Mass of Jesus, and the first time his disciples received Communion. The next day, on the cross, everyone would see the extent of this loving sacrifice, a sacrifice of everything He had, turned into a meal-sacrifice of communion, and anticipated in a sacrifice of wheat and wine.

In my next article, I will go through the parallels, one by one, as they apply to the Holy Mass I attend. Well, let’s hope this sequel won’t disappoint!

The Promised Neverland can be streamed at Crunchyroll.

- First Impression: The Holy Grail of Eris - 01.08.2026

- First Impression: Easygoing Territory Defense by the Optimistic Lord - 01.07.2026

- First Impression: The Case Book of Arne - 01.06.2026