Did you know that in bowling, when you get three strikes in a row, it’s called a “turkey”? So that means that this post, being the third in a week on the spectacular original anime series Turkey! Time to Strike, is in fact a Turkey turkey! (This is not the end of the dad jokes we’ll be foisting upon you this fine Turkey Thursday.)

It’s not often that we team up to sing the praises of an entire anime series, but that’s exactly what we—claire and NegativePrimes—are doing now! And not just because the pun was too good to pass up. We are genuinely stoked about this series and wanted to share the joy and make a case for why you, too, should check this one out.

Turkey is a bowling show that’s not about bowling, except when it is. It’s a trippy yet heartwarming story that makes some daring decisions for the plot, and yet pulls off every one amazingly well in the end. And best of all, it’s a veritable treasure trove for the kinds of allegories, analogies, metaphors, and deep reflections on life—and especially the life of faith—that we so love to geek out about here at BtT.

There’s a pretty big spoiler in the final moments of the first episode (and the after-credit scene), so if you want to remain pristine, go check out the premiere before reading further. There are also major spoilers in episodes 6 and 9, and of course, the finale, episode 12. So be warned, the spoilers in this post intensify as we go along… (See here for our spoiler-free First Impression)

Ok, with the warnings out of the way, let’s dive in, starting with a more fulsome description of the series, its themes, and its appeal!

Discussion Sections:

Spoiled Overview • Ep 6 – Blood, Sacrifice, & Clashing Values • Ep 7 – Living in the Paradox • Ep 9 – Of Twins and Inversions • Ep 12 – The Grand Finale or The Coming of That Giant Pinsetter in The Sky

A Turkey Overview

NP: Before we get started, I have to ask: Are you a fan of bowling, claire?

claire: Why, thank you for asking! I used to love (5-pin) bowling as a kid! Partly because I knew it to be a sport played by God and the angels. You could hear them bowling every time there was a thunderstorm. Badum ching!

NP: Cool, that’s literally a plot point in Rip Van Winkle! For my part, know what I love about bowling alleys?

claire: What, Nega?

NP: They’re so quiet—you can hear a pin drop! 😀 Thank you, thank you! I’ll be here all week! Seriously, though, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a story in which so much ended up riding on the fate of a single bowling pin. The first episode starts off normally enough; when I had my kids watch it, they confessed afterward that at first they were thinking, Why is dad having us watch this run-of-the-mill sports anime? And then things started glowing and people started floating, and my family’s jaws dropped. Then came the after-credits scene, and it just got better from there.

claire: Right? I have a soft spot for Bakken Record, so I was cautiously hopeful when I learned this was an original anime from the young studio, and wowzers, it did not disappoint! But there’s one problem…how do we describe this creative series that is far more than meets the eye? Take it away, NegativePrimes!

Turkey is a time-travel story that uses the contrasting values of different time periods to explore the nature of love, violence/sacrifice, and family.

—NegativePrimes

NP: Turkey is a time-travel story that uses the contrasting values of different time periods to explore the nature of love, violence/sacrifice, and family. Five girls on a high-school bowling team go back in time to the Sengoku era and help a feudal noble family overcome a threat to their very lives. Somehow, Turkey manages to reflect on the theme of femininity and gendered power dynamics at a depth on par with Apothecary Diaries, and does so in only 12 episodes.

claire: Well said! The way the series avoids relying on pat answers or glib resolutions is also something that really stood out for me, particularly when it comes to difficult interpersonal relationships and the kinds of cultural differences that implicate ethics and morality. Turkey! does not shy away from asking hard questions, nor does it hurry to provide easy answers in 23 minutes or less. Yet, all this profundity is wrapped up in such a hope-filled, joyous package, with great humor, a massive cast of winsome characters, each with their own distinct personality, and lively animation, with Bakken Record at its best. Chef’s kiss!

NP: You know, I’m glad you mentioned the distinct personalities, as that’s one area in particular where this story shines. Bakken Record has outdone themselves in taking a cast with no less than ten main characters and keeping them all distinct and engaging. It helps that the five girls from the present and their five counterparts from the past can be distinguished from each other by the style of clothes they wear and their hairstyles; and then within each group of five, individuals are distinguished by color themes, personal values, and personas. But it’s one thing to enable the audience to tell so many characters apart, and quite another to introduce them effectively and make us care for them in such a short series. So, hats off!

claire: A hundred percent. I’d love to know more about how the two character designers, Haruka Inade, who has worked with a similarly large cast on Oshi no Ko as chief animation director, and veteran key animator, Miyuki Matsumoto, went about this challenging task; I bet they have some stories to tell!

NP: Also, since we’re giving credit where credit is due, thank you for bringing this series to my attention! I didn’t even think to give it a chance until the moment you started geeking out and telling me to watch it!

claire: NP! (Haha!) I was so thrilled with the first twist that I couldn’t contain it! It’s been a blast to continue that geeking out with ya throughout the season.

Ok, now that we’ve set the stage, let’s dive deeply into some of the specific episodes, themes and imagery that so caught our attention with this wildcard series!

Episode 6 – Blood, Sacrifice, and Clashing Values

NP: Episode 6 really takes the story to a whole new level; for me, this is the point where the series went from “This is unique; I wonder what they’ll do next?” to “Holy Toledo, there’s actually some impressive story-weaving going on here.” Let’s recap:

Anzu, the youngest member of the Tokura family (the Sengoku main characters), reveals that her sister Sumomo is to be married off to another clan in order to obtain its protection, but only after she begins to menstruate. The modern girls are upset at the idea of marrying someone you don’t love, while the Tokuras are more concerned about survival. The resulting conversations lead the bowling team to reflect on what it means to understand someone even when you don’t share their values or “priorities” (to use the show’s term).

That night, in a minor coincidence, Sayuri (the modern girl known for her physical strength) starts her period and panics because she doesn’t have the relevant expedients that she’s accustomed to. Suguri (the second eldest sibling and acting lord of the clan) figures out what is going on and provides the Sengoku equivalents for her. When Sayuri asks how Suguri knows so much about periods, Suguri reveals, “I am a woman.” Whoa, shocker (but also foreshadowed earlier in the series)!

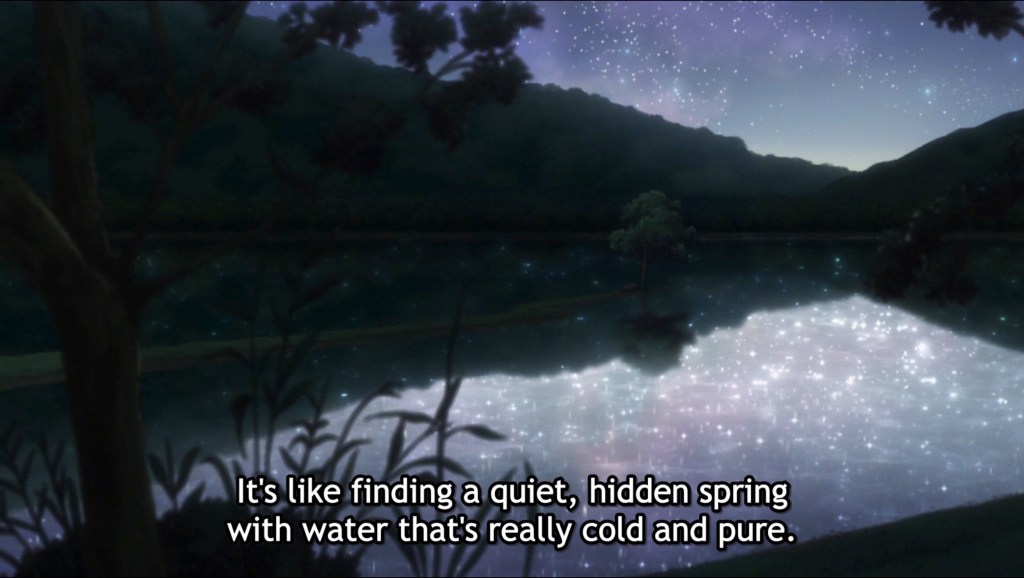

This creates a moment of bonding between the two, and Suguri tells the story of how her father ordered her “to become a man” for the sake of their people. She takes Sayuri to a small lake, the private place where Suguri comes whenever she is troubled. Once again, there is a discussion of the difference in values between the two cultures, this time not about love but self-sacrifice, and Suguri declares, “What’s the best way to serve others? That’s all that matters to me.”

But all of this is just setting up the main conflict of the episode: Bandits appear, and the Tokuras’ people proactively wipe them out, returning home covered in blood. Suguri, however, goes alone to her lake to wash herself off privately. Sayuri finds her again, and for the third time, a discussion of values dissonance occurs—about the value, and the taking, of human life.

Coming from a peaceful life, Sayuri is horrified at the idea of striking the bandits first and killing them before they act aggressively; for Suguri, preemptive killing is simply a necessity to preserve her family. Suguri states that she would kill someone in order to protect Sayuri; Sayuri feels that this would make her “unable to return,” that is, unable to remain the same kind of girl she is, even if she returns to her own time.

Then the bandit leader, who had survived the attack, appears and tries to kill Suguri in revenge. Sayuri, watching from a distance and seeing Suguri losing, has to make a decision: Will she help Suguri kill the bandit leader, or will she stick to her principle of never taking a life? Now the conflict in values has moved from mere discussion to reality, to a crisis that demands a decision and action.

In the end, Sayuri intervenes and saves Suguri’s life. As Suguri is poised to finish off the bandit leader, Sayuri states that she can’t watch—but she will stay. She won’t flee from the consequences of her actions. And as blood drips into the lake, Suguri reassures her that Sayuri is still the same person she was before, strong and kind.

The motif of blood ties the violence of the latter half of the episode with the menstruation image of the first half, as does the theme of femininity, for this story is not just about what it means to be a good person; it is also about what it means to be a good woman.

claire: This was such a powerful episode. What made this final sequence hit so hard to me, was the realization that Sayuri’s convictions were so strong and definitive because she had never experienced a life-or-death situation. Instead, like many of us, she lived in an era and a society (and a home) that sheltered her from the kind of hardship and cruelty that would cause someone to contemplate taking a life—so much so, that she couldn’t even conceive of such a thing.

And this realization made me consider how much we actually “outsource” our morality; that is, we live by convictions that don’t cost us anything, either because we will never be challenged on them (they are majority-culture values), or because some other segment of society, part of the world, or future generation pays for our privilege, insulating us from the implications and consequences of our values (or lack thereof) so that we don’t need to face them.

NP: I am reminded of two things. The first is a story about how a pig and a chicken wanted to thank the farmer who took care of them, and so were discussing what they could do. The chicken quipped, “Let’s give him a breakfast of bacon and eggs.” The pig responded, “That’s easy for you to say. For you, that’s an inconvenience; for me, that’s total commitment.” For Sayuri, being good meant being a “chicken” because she hadn’t ever had to put her life on the line; but even in our own peaceful day, growing up means dedicating your life to whatever God has called you to. This is what is meant, after all, by taking up our cross.

claire: That’s a great point! And you’re getting at something that, I’d say, often comes to us a little later in our walk with God, when we start to grasp what Jesus meant when he said that if we call someone “idiot!,” we’ve committed murder or when we look at someone lustfully, we’ve committed adultery. When we’re young, and things are still so black and white, we may take pride in the fact that we would never kill or harm someone, like Sayuri. But as we grow older, and God tenderizes our hearts and opens our eyes to see more fully, more honestly, the effect we have in the world, we start to understand that, in our hearts, we have killed, we have harmed. But this isn’t to shame us; but rather, to humble our hearts, and make us leap at the outstretched hand of God, who invites us to draw near to him, despite our inability to truly live up to our values.

But what was the second thing, NP?

NP: The second is a line from the Lord’s Prayer: “Lead us not into temptation.” The word “temptation” here means simply “trial” or “testing”: In other words, the prayer is asking, “Don’t let our convictions be put to the test.” Tests will come anyway, but we should not blithely look forward to those moments with self-assurance that we’ll pass—that’s pride, which goes before a fall. Rather, we should pray “Lead us not into temptation” while having faith that should any test come, God will be with us through it—as indicated in the next line, “But deliver us from evil.”

claire: Ooo, I like that! Wow. I have a second thing, too! The other thing I so appreciated about this scene is that it keeps on unfolding, forcing Sayuri to begin to face some of the harsh realities that she’s never had to consider before. And new questions arise for her: If she rejects killing, does that mean she also rejects her friend, who is revealed to be a killer? Does she allow that friend to die in order to maintain her rejection of and non-involvement in killing? Sayuri is pushed and pushed, and what I love is that she doesn’t really resolve this challenge to her morals. She simply acts in the moment, for better or worse, and we’re left with the moral tension unresolved. This is bold writing, resisting the narrative imperative (at least in the Western classical tradition of the three-act story structure, setup, conflict, resolution) to tidy away the loose ends of residual conflict. But it’s also more true to life. One of Sayuri’s core values has been shaken; it’s going to take time for her to navigate this and process the implications of what happened.

One more detail: The final shot of this sequence—it’s just so elegant. The daisy, which represents innocence and beauty in Japanese flower language, is soiled with blood. It doesn’t become blood, it doesn’t shed blood; but it encounters the cruel reality of bloodshed and is forever stained.

NP: I can’t help but feel that by linking two forms of bleeding, menses and wounds, Turkey is suggesting that caring for others always involves a kind of self-sacrifice or even a sort of symbolic death (a death to self, at least). After all, a woman’s period is a sign that she is capable of bearing children, and having helped my wife through several pregnancies, I have seen firsthand how much sacrifice is involved in carrying a child to term. (That’s not even taking into consideration the sacrifices needed to raise them after birth!)

So in this story, menses become a sign of caring for others more generally, specifically in the case of women (fitting for our cast), but also more generally for all people. And it is a reminder that love for others demands giving our lives, even (again) in a time of relative peace. Where our lives differ from those of Sengoku Japan is that the need for sacrifice is more veiled, requiring us to remind ourselves more intentionally that we are called to carry the cross every day.

claire: Yes! I agree—sacrifice is at the heart of this series, along with a sense of urgency for the modern world, represented by our bowling girls, to recapture the value and goodness (for lack of a more sophisticated term!) of sacrifice in an era that is so opposed to any and everything perceived as infringing upon our rights to independence and the pursuit of our own happiness. What is so very palpable in the dialogue from both Sumomo and Suguri as their situations unfold is how highly the Sengoku sisters value what it is that their individual sacrifices can accomplish for others—for their siblings, family, and community.

Yet, this isn’t the final word on the theme of sacrifice. What later episodes reveal is that there are some forms of sacrifice that are not holy and good, but instead perpetuate injustice. We continue to see these two values—sacrifice and justice—dancing around, against, and alongside one another right up to the final moments of the series.

Episode 7 – Living In the Paradox

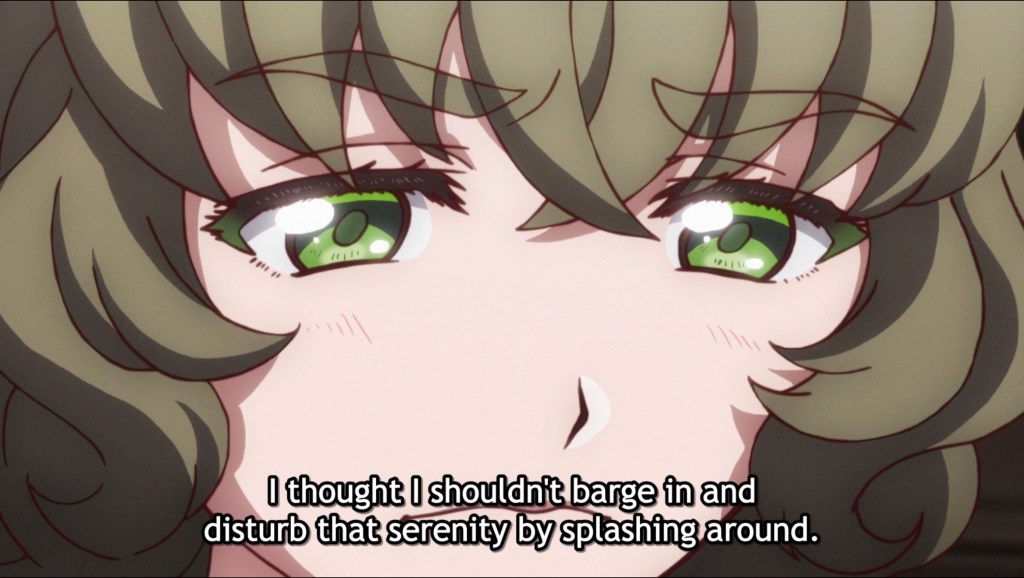

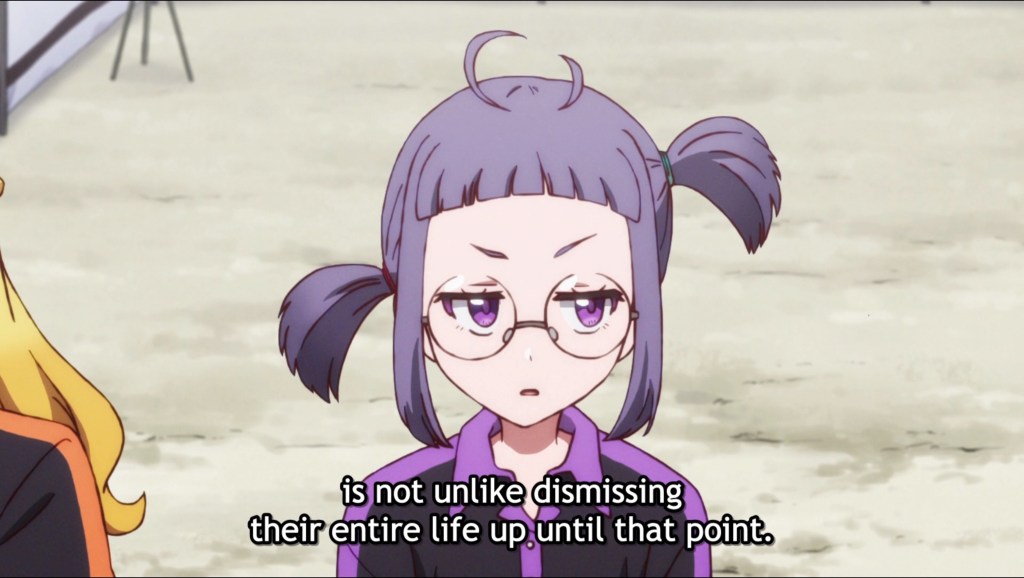

claire: I was intrigued by Turkey after the first episode twist; impressed with it following episode 6 and the way it chose to “sit in the discomfort” of unresolved cultural differences and moral tensions; but I was blown away when, in the following episode, an entire sequence was dedicated to the girls reflecting together on the problem of differing values. Specifically, Sayuri is sharing her thoughts upon hearing Suguri’s story about taking up the guise of a man. Here it is, in screencaps:

What I love about this conversation is that, like Sayuri’s actions in episode 6, it maintains a paradox, holding two seemingly contradictory things together in tension: Giving people space, yet not leaving them alone.

In her latest book, Strong Ground, Brené Brown writes about how essential recognizing and maintaining paradox is to healthy dialogue and societies, and how critical it is for us to wrestle with the resultant complexity and nuance, rather than seeking to sweep it away with the black and white—and consequently judgmental or defensive—thinking that we often embrace. Such dichotomous thinking provides relief from the tension of open-endedness, but it also turns the world into a war zone, peopled with allies and enemies. Meanwhile, Father Richard Rohr points out in his book Falling Upward that paradox lies at the very heart of Christianity and the life of faith, conveyed most profoundly in the crucified Savior, and God’s strength made perfect in our weakness.

My point in sharing all this is to underline again the excellence of the writing in Turkey, from veteran director Susumu Kudou and newcomer script writer Naomi Hiruta. Their storytelling resists trite resolutions to nuanced discussions and instead requires both the characters and us as viewers to get comfortable with not always having “the right answer” for every situation. Instead, the girls are forced to take a more relational, connected approach, valuing the humanity of others over the relief of having tidy answers.

NP: I think the best summary of what you’re saying that I’ve ever read comes from a passage in Glen Cook’s The Black Company (no, not that kind of “black company”!), a dark fantasy series. I don’t have the exact wording at hand, but one of the characters essentially states, “Objective good and evil do exist, and we should seek the good; but we also live in a world that very often obscures where that good lies, and so we stumble about trying our best.”

Denying the first half of this is moral relativism; denying the second leads to either self-righteous arrogance or despair (depending on whether someone thinks themselves absolutely good or absolutely evil); and both are “all-or-nothing” approaches that oversimplify life. But dealing with nuance requires us to think—it’s easier to cast everything in terms of black and white than to face the complexity and the beauty of colors. Or as St. Therese of Lisieux writes, “If all flowers were roses, the fields would not be arrayed with lilies.” There is not just one kind of goodness that fits all situations; God created varieties for a reason, and he gave us minds to discern them. Yet all instances of goodness serve, in the end, to direct us to the one ultimate Good, namely God.

claire: Amen!

Episode 9 – Of Twins and Inversions

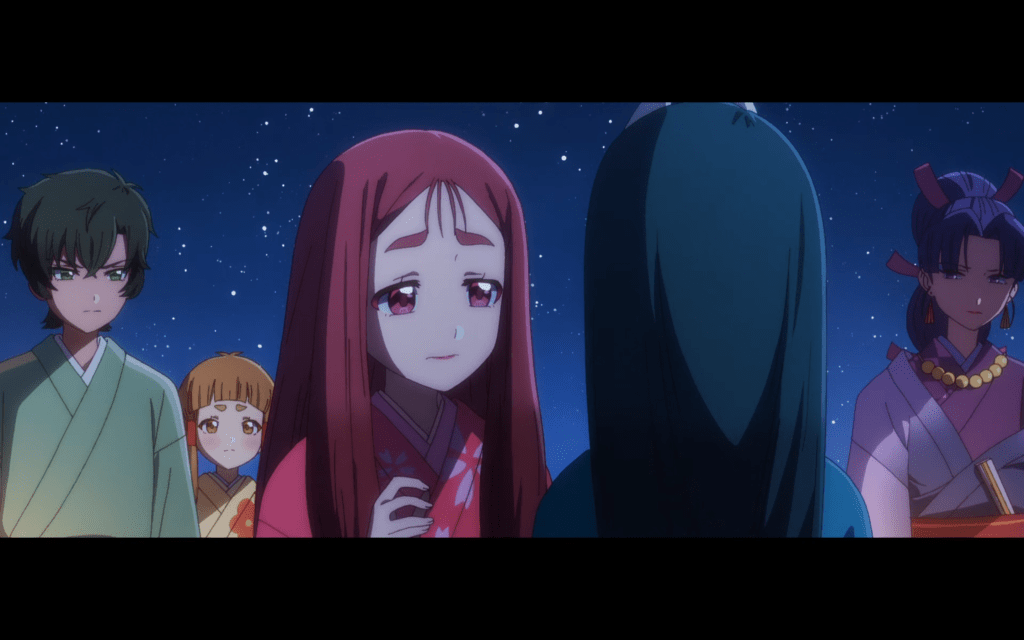

NP: Episode 9 opens with…a new opening! Or rather, a new version of the same opening: The roles of the bowling team and the Tokuras are switched, with the Sengoku sisters playing the electric guitars and other instruments, and some intriguing imagery appearing. In particular, the very end of the OP has Akebi’s mask that she always wears fall to the ground and…split into two perfect halves. This foreshadows the reveal that Sumomo and Akebi are twins. What is more, Akebi was supposed to be killed.

It’s not entirely unusual, alas, to find cultures in which twins were thought of as a sign of misfortune, and thus to have one (or both) of them killed. In Turkey’s setting, twins are called “sullied,” defined as “omens of misfortune,” and the second-born one is to be done away with. Furthermore, a court fortune-teller predicts that they will someday bring evil upon the land otherwise. So a link is forged between superstition, (false) religion, and ritual sacrifice. This contrasts starkly with the self-sacrifice theme established previously in the series.

The sacrificing of an innocent individual who is blamed for the misfortunes of the people is a theme that should sound familiar. After all, Caiaphas says that Jesus should be treated this way: “But one of them, Caiaphas, who was high priest that year, said to them, ‘You know nothing at all. Nor do you understand that it is better for you that one man should die for the people, not that the whole nation should perish’” (John 11:49-50). This is hardly the first instance of this sort of thing, however. René Girard—a French intellectual whose studies of this very occurrence across many cultures converted him from atheism to Christianity—called this the Scapegoat Mechanism.

claire: Wait a second, what?! That’s incredible! What a testament to God’s ability to take what the enemy intends for evil and turn it to good! Wow. Ok, please continue…

NP: Sure! In brief, the Scapegoat Mechanism is the process by which a society tacitly (perhaps not even consciously) blames some person or group for its problems. The purpose is not so much to find an explanation for disaster as it is to find an outlet for the inherent violence that human societies cannot escape. By agreeing to focus their violence on a specific demographic, the rest manage to secure a peaceful existence for a time (at least for them). And so, civilizations from ancient times to modern have targeted twins, lepers, immigrants, Jews, and countless others, justifying their violence in the name of the greater good, spinning deceitful stories to hide their sin.

Like me, Girard started out as a scholar of literature. He traced this pattern of violence and justifying narratives through culture after culture, through story after story. But when he encountered the Bible, he found a story that bucked the trend: The Old and New Testaments revealed that the violence of the Scapegoat Mechanism was wrong, that the targets were innocent. It unmasked the lies used to justify violence.

And so we return to Akebi’s mask. The splitting mask, two halves from one whole, reflects the nature of the twins, two births from one pregnancy. The mask, then, represents both girls—each has been hiding her real identity: Akebi with an obvious literal mask, Sumomo by playing the false role of a single sister without a surviving twin. And like the deceptive stories that mask violence and seem to keep the peace, the twins’ “mask” hides the reality of scapegoat violence in their culture.

But then the mask breaks! The deception is revealed, and Akebi steps out into the light of day. The Scapegoat Mechanism has been exposed.

That’s a good thing, right?

It is, as it exposes the violence in their society. But now that the violence is out in the open, we can expect to see it rear its ugly head—and by the end of the series, it bursts forth with a vengeance!

claire: This is so good! Selah. And of course there’s another type of twinning at the very heart of Turkey as well! It all comes together in this episode, starting with that gorgeous one-off OP (which literally had me sitting up and cheering as I watched! I knew this episode was going to be EPIC as soon as we hear Sumomo’s seiyuu instead of Mai’s in the intro song). In this moment, the device of the entire series is laid bare, as the parallels set up between the girls of each era come to fruition. Each girl now has her counterpart, her “twin”, we might say, as Rina’s masked mirror self is finally revealed with Akebi’s appearance.

NP: Oh, I like that! I hadn’t thought of it that way!

claire: Right? But not only is the inverted OP and the pairing up of the characters (according to color scheme, of course!) a whole lot of fun, it also touches on a powerful truth that runs throughout the series: the healing power of friendship. Granted, that’s an anime classic, but I think it’s worth repeating in these days of AI therapists and increasing social isolation. Our modern-day girls each carry their own hidden baggage to the past, where it leaks out in the high-pressure situations they find themselves in. Yet, each girl ultimately finds the wisdom or courage she needs to confront her troubles head-on, thanks to a newfound friendship with her Sengoku-era “twin.”

NP: You could say they put the “win” in “twin”! 😀

claire: Haha! Totally. And there’s something really cool going on with how these twinned pairs affect one another; another inversion. For each bowling club member, it is the individual story of the Tokura sister she is “twinned” with that equips and heals her to confront her secret burden, while for the Tokura sisters, it is the collective action of the modern-day girls that sets them free.

So there’s this beautiful symmetry, where the “collectivist” Tokura are operating on an individualist level, and the “individualist” bowling team finally comes together fully and completely, to act in unity. Each set of girls puts on the mode of being that is more natural to the other, bringing the two groups into harmony.

The two sets of characters are “twinned” from the beginning, as seen here in the OP.

Episode 12 – The Grand Finale Or The Coming of That Giant Pinsetter in the Sky!

claire: The finale was all I could have hoped for and more. I laughed, I cried, I pumped the air with my fist, and went full victorious shonen hero on that episode. (The music score was fantastic during the climactic sequence!) I’ve written about the finale a few times already, in fact! On the themes of discernment and faith, grace, and the miracles we encounter only in the gutter.

So here, I want to pick up on a smaller detail: the omen or the “prophecy” of the shaman. What I find fascinating is that, broadly speaking, the omen was somewhat accurate, in that Sumomo is not actually destined to remain and help her family, fulfilling her duty as a Sengoku era noble (and political pawn), but instead, she was destined to disappear…into the future. (That’s right, the giant pinsetter in the sky scoops her up too and deposits her in modern-day Tokyo, where she goes by the name Haru and initially suffers from amnesia, until she meets little orphan Mai one day and it all comes flooding back to her…I’m not crying, you’re crying!)

Now, this is completely supposition on my part, but what I’d suggest happened here is that the shaman misinterpreted a legitimate prophecy from the deity of that world, and turned it into a word of death and punishment, informed by both the cultural norms of the time (superstitions about twins), and his own thirst for dominance through violence and intimidation. He heard what he wanted to hear, and what would be acceptable to mainstream culture at the time, and so he missed the truth.

It makes me wonder, how often do we do this with scripture? Interpreting it through our own mainstream culture and desires for affirmation? Do we, like the shaman, “seek” God with our confirmation bias on full throttle? Or are we open to the Holy Spirit who both convicts us of sin and unlocks the mysteries of the universe to us?

NP: There is certainly a scriptural precedent for this. Remember the story of Balaam’s Donkey? Balaam was a legitimate prophet, and God used him to foretell the coming Messiah. Yet when God told him to go to Balak, Balaam’s interpretation of God’s message was twisted by his desire for Balak’s money. God didn’t send the angel to threaten Balaam because Balaam went to Balak; after all, God had explicitly given him permission to go. Rather, it was the spirit in which he went that was screwed up. God had to send the angel (and the famous talking donkey) as a warning to Balaam, lest he end up telling Balak what he wanted to hear instead of God’s actual message.

claire: Great point! Now that’s making me wonder whether the false prophets routinely mentioned in the OT were likewise often mishearing or misinterpreting, more than simply falsifying, the “word of the Lord”? (I’ve always just considered them to have been straight-up charlatans, but perhaps they started out with a genuine gift and calling, but allowed worldly concerns to twist and contort their service to God…) But I digress. Back to the finale! We got a ton of “after-credit” content, tying up all the loose ends! Definitely felt spoiled with that. Any thoughts, NP?

NP: I’d like to see more after the last episode ended.

claire: Never enough Turkey, I see! (Haha!)

NP: What happened after everyone involved found out that Haru was Sumomo? Surely they would have been excited and had a tearful reunion. And what about Nanase’s dad? Odds are, he met Sumomo in the past, too—what would he and Haru think after running into each other in the modern era?! And what’s his story—how did he get back to the past, and what was his adventure there?

claire: Oh my goodness, of course they met in the Sengoku era! I’d love to see that reunion! I bet it was pretty awkward. After all, Nanase’s dad basically stole away the Natsume-shaped pillar they all relied on!

NP: And then, what happened to the museum exhibit? Did everything stay the same, and does that imply that the other girls in the past besides Sumomo were killed anyway, or that the museum simply didn’t find any evidence to the contrary? Or did the exhibit itself change?

claire: Yes, another post-credit scene would have been marvellous! Maybe we’ll get a manga adaptation with a few extra Easter eggs! Here’s hoping.

ED

Well, if you’ve made it this far, hats off to you, my friend! We hope you’ve enjoyed this deep dive into the original anime series that, for us at least, just kept on giving, week after week. As far as we’re concerned, there can never be enough Turkey!

And remember, friends, in bowling as in life, there’s always the second throw!