Welcome to the 12 Days of Christmas Anime! Starting today and marching right through the 25th, we post about Christmas anime each and every day in hopes that these little connections will point you to the joy, love, and redemptive meaning of the holiday. We might post a piece of fanart, chat about a classic “Christmas anime song,” or do a deep dive into a Christmas episode—which is what we start off with today, with our first-ever “12 Days” look at SANDA, this season’s Christmas-themed anime series!

Santa Claus has long drawn the ire of Christians who complain that he, instead of Christ, has become the center of Christmas, and the focus of a holiday that, like Snoopy, has gone commercial. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but in recent years, there’s been a reclamation project underway, with many parents rejecting telling the tale of Santa to their children (“Why would I lie to my kids?”) and Christians instead emphasizing St. Nicholas, the inspiration for Santa. So you’d think that this Christian aniblogger would, at the very least, feel conflicted about SANDA, the currently airing anime about Santa Claus, based on Paru Itagaki’s manga series. But ho ho no, I don’t feel conflicted one bit! After all, it doesn’t take more than a few episodes/volumes to notice a fundamental parallel between the Santa of SANDA and Jesus: namely, their care for the children.

To be sure, it feels like a strange comparison to make at first. After all, SANDA begins with an attempted child murder, as middle schooler Shiori Fuyumura stabs her classmate, Kasushige Sanda, in the chest in order to summon Santa Claus. And because this is anime, it works! Sanda, who already knows that he’s in Santa’s family line, transforms into a full-grown, ultra-buff, old-man Santa, and along the way discovers super cool powers as he attempts to help Fuyumura find her missing friend, Ichie Ono.

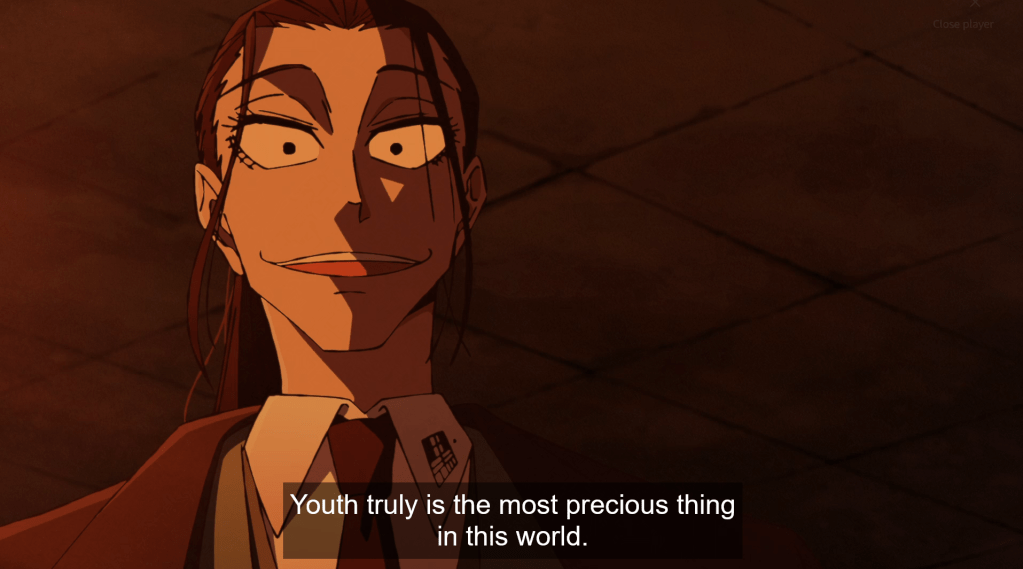

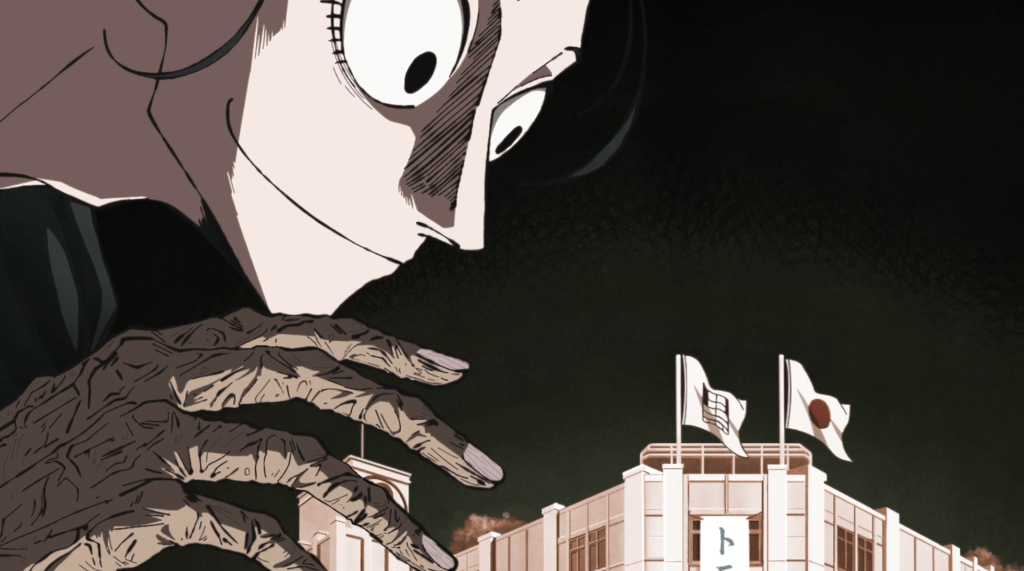

But in what kind of world would any of this be necessary—or allowed? Just like in any good anime, parents appear to be out of the picture in this world. However, SANDA explains this absence through a dystopian vision of future Japan. Fuyumura, Sanda, and their classmates not only attend their school—they live and are raised there. I say “raised” and not “reared” because it feels like they’re a commodity, like cattle, being raised for some purpose. Over and over, the adults in SANDA (like the evil headmaster) and even the children themselves note how valuable they are in a society that lacks children. They’re so valuable, Fuyumura points out, that they commit crimes unopposed; they can even get away with murder.

But this is no utopia for kiddos. It’s a dark, bleak, and sometimes gross vision of what would happen in such a scenario where children are being cultivated for state purposes. Sexuality is involved here, as (spoilers ahead for episode five) the school attempts to keep the kids prepubescent as long as possible, which unsurprisingly leads to extreme (Niko) and messy (Ono) sexual awakenings as a result of the repression.

In addition, the protein-packed but “crappy” food they’re forced to eat, the (again) evil headmaster, the utilitarian look of the school’s architecture, the congregational observance all the students must participate in—the list goes on and on—make it a prison as the school seeks to control the children. It all feels like a child’s nightmare out of a Roald Dahl book.

The adolescents of SANDA don’t get to be traditional kids. When children don’t develop in a loving, nurturing environment, they tend to struggle mightily as they grow into adults—and that’s on full display here with Daikoku Welfare Academy. Sanda is a bundle of nerves, but he’s easily the most “normal” kid among the main cast; others kidnap and torture their friends, stab classmates, become obsessive, and run off. Raised without love, their childhood and future alike are being stolen away.

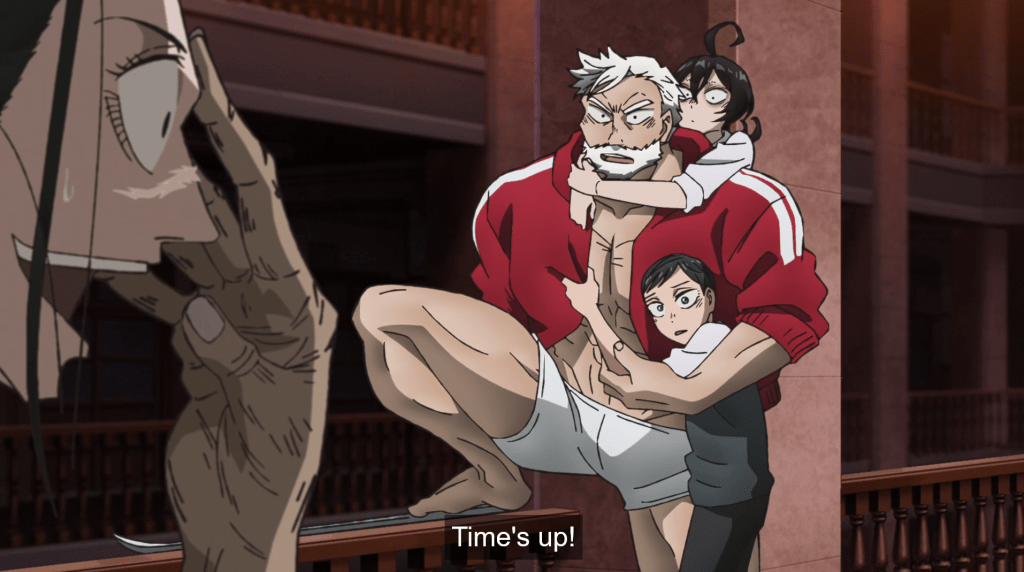

It’s in this context that Fuyumura’s violent act, which is initially shocking for the audience, becomes understandable. Out of desperation to get help to find Ono, she does what is necessary to turn Sanda into Santa. Once the transformation occurs, Sanda becomes the jolly old man physically (though with a six-pack), and in his mindset too as his mentality shifts. Sanda is a child; Santa is an adult with a strong desire to protect children.

For instance, when fighting Hitoshi Amaya, a close friend who has turned traitor and become a torturer, Santa feels a strong desire to protect him, even as he tries to stop him. And so he saves Amaya, despite the boy’s betrayal. And when the headmaster of Daikoku Welfare Academy, Hifumi Oshibu, shows his true face (a callback to Dahl’s The Witches?), Santa becomes irate and puts himself on the line to rescue the children and battle the headmaster, who embodies the evil, abusive institution. He will protect the kids.

I can’t help but draw parallels to how we treat children today. In SANDA, the kids don’t quite understand that they’re being raised abnormally and that it’s hurting them; I feel something similar is happening now, with parents and children not quite understanding the harm that comes with raising children outside the wisdom and guidance of scripture. Without that foundation, parents are left to pick and choose from what they experienced growing up, what the latest studies are telling them, and how the ever-shifting culture portrays good parenting. It’s no surprise that with a “sandy” foundation (Matthew 7:24-27) like that, the result would be confusion, depression, anxiety, violence, and more struggles for kids.

Meanwhile, we know how commercialized Christmas has become. Charlie Brown spoke of it fifty years ago, but we didn’t heed that wise child’s warnings. Things have gotten far worse as we seemingly live to consume, most of all during this holiday season. The impact of doing so is bad enough on adults and on the world, but do we think about how it impacts children in their emotional and societal development? The harm that we’re doing by pursuing such excess and modeling it for our kids?

We may struggle to get it these days, but this was something that Jesus understood. His concern for children was unusual in first-century Palestine, so much so that among all the miracles he did, his teaching about kids is still emphasized in scripture. When his disciples tried to keep children away from Jesus, the Master was “indignant” and told them, “Let the children come to me; do not hinder them, for to such belongs the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:13-14). Jesus saw the children. Jesus valued the children. He even followed the words above with an exhortation for us to be like the children. And in this, he was unlike the world and even his own disciples.

SANDA gets it just right in showing how this “savior” of children loves and wants to protect them—as opposed to our cultural and commercialized Santa, whose toy-making and delivering offer only a safe love, one that doesn’t require self-sacrifice or courage. Because of this, the Santa of SANDA often feels more like Christ and less like our caricature of Santa Claus. Maybe this is why the students of Daikoku Welfare Academy instinctively celebrate him as the “God-Man,” once Santa appears before the student body.

Yep, that’s right. When Santa bursts into the phony funeral that Headmaster Oshibu arranges in order to draw him out and assassinate him, the children wonder if it’s God himself who has just shown up.

Sanda is no god, but Jesus was—fully man and fully God. And this “God-man” cared about the littlest ones; he cared about the children. We could even say that he comes across as a doting parent, willing to sacrifice his time to linger with them and put his hand on their heads. He wants to be with them and bless them.

Isn’t it just extraordinary that Jesus acts in such a fatherly way toward the children? He’s modeling something here; while Christians now commonly see God as “Father,” Jesus opened the door to that relationship by personally referring to God as his Father and teaching us to do the same (Matthew 6:9-13). And he went even further than that, also acting and speaking like his Father, and equating himself with him (John 5:19; 8:28; 14:10), while telling us to be like the Father and enjoy him personally!

Understanding how fatherly Jesus is helps us comprehend how he wants to bless us as adults too. You see, we are also children—children of God. Some of us have been adopted into God’s family, having come to know him through His grace and receiving sonship. And others are lost children, like the Prodigal Son, whom God desperately wants to adopt. He is like the father running to his wayward son in that parable—the Heavenly Father who would send his “only begotten Son” to Earth as the most expansive invitation to all humanity to come home that the cosmos could ever see.

What an incredible love! And what a contrast to the exploitative adults of SANDA, and even to the real world that we’ve shaped, and which is impacting the kids here and now.

But there is hope. We are in the Advent season, which is a reminder that Christmas is coming. In SANDA, Santa Claus will come to break the children out of their school prison; in reality, Jesus has come to free us from our chains, and will be coming again one day, too.

As the 25th approaches, let’s remember this hope born on Christmas Day; let’s remember that he has come to protect and save the children, both the truly little ones and the grown ones too—all of us in need of our Savior and our loving Father.

- First Impression: Kunon the Sorcerer Can See - 01.05.2026

- First Impression: Hana-Kimi - 01.04.2026

- First Impression: Sentenced to Be a Hero - 01.03.2026

Great article! I really liked this line, it popped out for me for some reason. I’m only on EP1 but I’ll be watching this anime now a bit differently and keep an eye on the parallels 🙂

SANDA gets it just right in showing how this “savior” of children loves and wants to protect them—as opposed to our cultural and commercialized Santa, whose toy-making and delivering offer only a safe love, one that doesn’t require self-sacrifice or courage. Because of this, the Santa of SANDA often feels more like Christ and less like our caricature of Santa Claus.