Part 2 of 2 In celebration of the 10th Anniversary of Puella Magi Madoka Magica!

And then there was the sequel movie, Puella Magi Madoka Magica: Rebellion. I’ll admit it, I lost sleep over this one. What can I say, sometimes I get a little (over)invested in fictional tales. But in my defense, the Madoka series was what sealed my love for anime and taught me to expect to hear from God through it.

In Rebellion, Homura either becomes evil or is at least willing to appear so, in a possibly necessary/possibly misguided effort to save her beloved friend Madoka from a renewed threat by Kyuubey and the Incubators, who seek to capture and exploit Madoka for their own gain. Which is to say, Homura goes full-blown yandere. PTSD is certainly a factor in her transformation: at least eight years spent reliving the deaths of her friends every 45 days or so, progressively isolating herself from them in each “reincarnation” in order to better her chances of saving Madoka, failing over and over again to live up to her wish of becoming strong enough to save her friend or even grant that friend’s (repeated) dying wish of preventing her from becoming a magical girl in the first place—Homura had been carrying a heavy burden for a very long time. No wonder she snaps. But to see her finally do so is utterly heart-breaking. The onion-chopping ninjas definitely paid my house a visit as I watched it play out.

The ambiguity of Homura’s explanation for her actions—claiming she has become a demon for the sake of love—and the film’s ending—does she commit suicide after losing her mind?—kept me awake with questions. Did Homura truly become evil? Or had she been deceived by Kyuubey? Was it love or selfishness that drove her? Was she actually a demon, a creature worse than a witch, or was that only her self-condemnation speaking? To say the ending of Rebellion is open to interpretation is an understatement.

But no matter how you read it, there is an eternal truth buried in Homura’s tragic end:

a concept cannot save.

Neither can knowledge, understanding or a change of philosophical system. Not even a good deed or the ultimate sacrifice is enough. Instead, in Rebellion, Homura reveals humanity’s deep-seated, desperate need for salvation through personal relationship with our God.

Madoka’s messianic wish in episode 12 of the series triggered her transcendence and transformation into a concept. A universal, omnipresent one that could be personified, but a concept nonetheless: the Law of Cycles. This concept was not enough to heal Homura. Madoka as the Law of Cycles (or Madokami, as she is known in some corners of the interweeb—a combination of her name with the Japanese word for god, kami) could not restore Homura to wholeness following the eight years of repeated loss, violence, and failure, let alone the subsequent trauma of ultimately losing her friend to transcendent oblivion, retroactively erasing her from human reality so that Homura could not even share her memories of Madoka with those who survived. In fact, Madokami’s marked non-presence in Homura’s life meant that Homura gradually comes to believe herself crazy for remembering (and mourning the loss of) a friend whose name no one else can even recall. Madokami’s eventual appearance at Homura’s apparent deathbed was too little, too late.

What Homura needed was to be loved and to love in return. She needed relationship. To her mind, relationship was far more important even than rescue from her suffering.

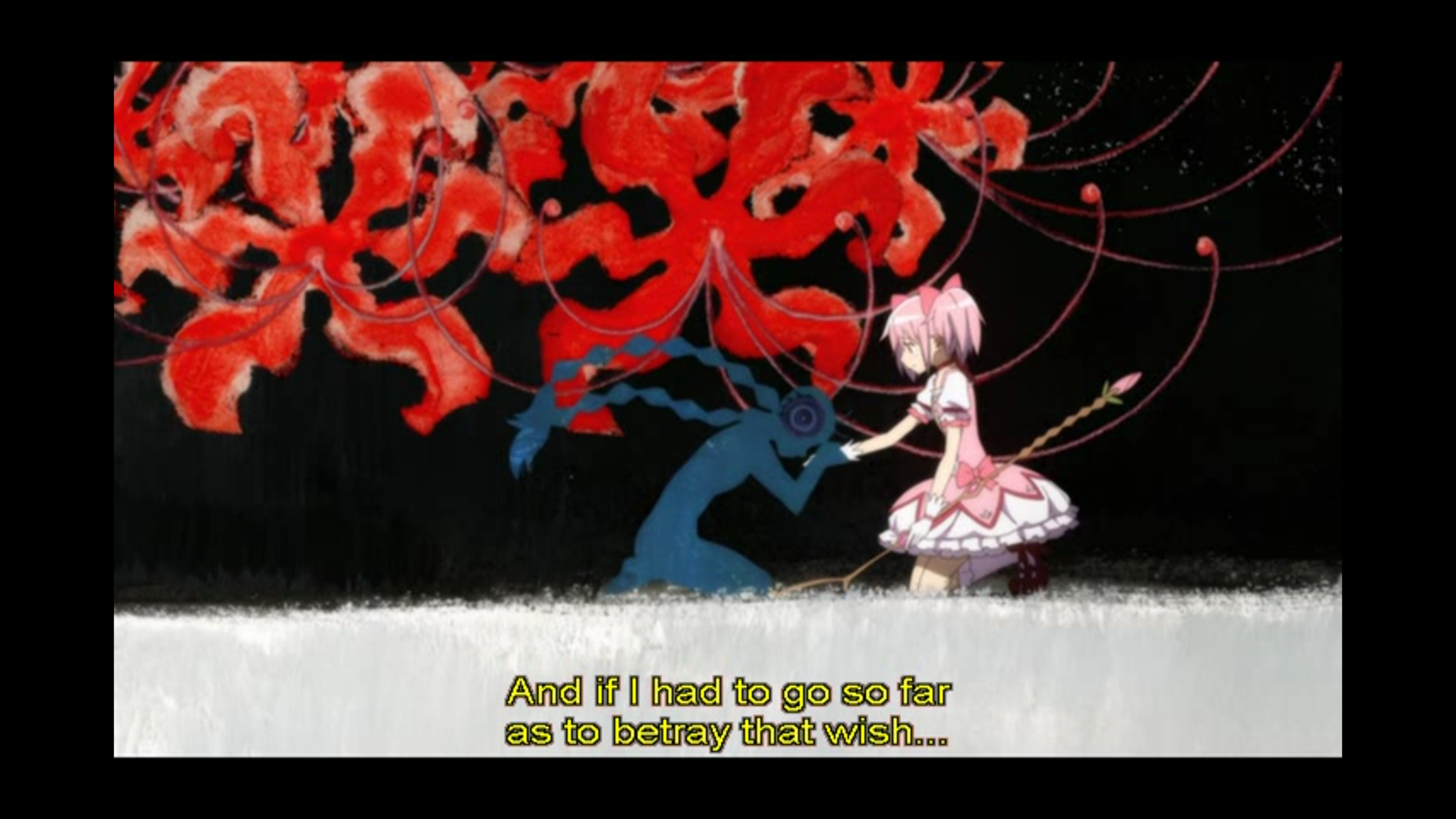

The lycoris or spider lily seen here (and in place of Homura’s head in her witch form, Homulily) symbolizes death and reincarnation, and is thought to lead souls in the afterlife. Check this out for more details.

And is that not so often the case for all humanity as well? We are more acutely aware of our need to be loved than our need for salvation; more aware of our relational brokenness than of the weight of sin. Of course, these things are intertwined, but when we listen to what people are crying out for in this hurting world of ours, it is more often articulated as a desire to be loved well, and an immediate need for trustworthy relationship, than for the somewhat more distant-seeming concept of salvation.

Madoka as the Law of Cycles denied Homura this loving relationship.

So Homura breaks it. She rips apart the concept and forces Madoka to become a person again, even if it means that they will eventually become enemies because of what Homura has done. A concept—as full of grace as the Law of Cycles may have been—could not save Homura. This was the case with the Old Covenant too, the laws of the Old Testament, which pointed to a gracious God and provided a mechanism for redemption, but could not actually save. For that, a person was needed—one who could satisfy the balance sheet once and for all, rendering it obsolete, rather than just editing it or trying to tear it up.

The need for a personal redeemer makes sense when we consider that the problems faced by the magical girls—and humanity as well, since the Garden—are born of broken relationship. They are rooted in the attempt to exert control in relationships and the messy consequences this brings. Just think for a moment. Each of the girls’ wishes are relational in nature: Sayaka wishes for Kousuke to be healed, in hopes that it will draw him closer to her; Kyouko wishes to restore her father and family to a state of harmony and happiness; Madoka wishes to save all magical girls; Homura wishes to save Madoka. Only Mami’s wish—to live—is not relational, and she is the one among them who remains true in all the realities Homura experiences, dying rather than transforming into a witch. And so it must be, since it is in dying that Mami’s wish to live is subverted, whereas for each of the other girls, the cost of the wish is the destruction of the relationship that it was meant to champion. Something more than changing the rules—exchanging the wish-curse balance for the Law of Cycles—is needed to fix this broken state of affairs.

In the Garden, humanity traded relationship for a concept: exchanging trust in God for the knowledge of good and evil, perfect discernment, god-level understanding. No further concept or philosophy could redeem this mistake. Only a personal redeemer could achieve this. Only a person can speak into our despair or take us by the hand when we are lost and alone, frightened or confused. That’s the real heartbreak for Homura. She needed a person to save her, to hold her and walk with her.

In the world of Puella Magi Madoka Magica, there is no possibility of a personal savior. It is a world shaped by the Buddhist principles of reincarnation, karma and the path to transcendence. As such, to fulfill her wish to become a savior, Madoka must leave her human form— she must transcend her human existence and become something else. And it’s the fact that she steps into abstract “thing”-ness that breaks Homura.

In the real world, God loves radically and sacrificially like Madoka and even more extremely, while yet remaining a person. Though this may sound obvious, it’s actually one of the most difficult things for us to grasp—the concept of balance, of tit for tat makes so much more sense than a living, breathing, loving relationship with God. So we often change him into an angry person, a capricious, or distant one who needs appeasement or some kind of bribery. Or we shift him into “thing”-ness and make him a concept, a set of rules, disembodied and stripped of emotion. But in reality, God wears his love in the shape of a living person; he too is relational. That’s where we get it from, after all. He made us to fit snugly in his arms, to find our safety and salvation in relationship with him. Instead of holding himself apart from us in some higher plane of existence, scripture tells us that he reveals to us his inmost heart and deepest mysteries (1 Corinthians 2:10). You can’t get much more personal than that.

The original Madoka series takes us right up to the edge of the gospel, revealing the tyranny of a karmic philosophy that can only ever balance out fulfilled wishes and curses. The show even highlights the need for grace born of sacrifice. But it stops short here. Madoka is not the Messiah. In becoming a concept, she merely shifts the balancing scales onto a higher plane, her transcendence to Madokami necessitating the emergence of an equally weighty curse, expressed in the form of Homura’s (self-)destructive demon.

Madoka is not the Messiah, but she does reveal what the Messiah needs to be, namely, a person with whom we can have relationship. A savior who is both capable of relationship with us, and who is willing to stoop down and do life with us. Someone who does not just come to our rescue at the end of our days when the curse of living in a broken world, battling to do good, finally catches up to us, like Madokami with the magical girls, but rather someone who draws near and stays close day in and day out. Who makes it possible for us to actually live and thrive, and not just survive. A concept just can’t do that, and Homura knew it. She wanted relationship with a personal savior. She wanted it desperately enough to throw aside everything else and go after that one thing.

Homura’s story is humanity’s story.

But fortunately for us, we don’t live in her world.

Puella Magi Madoka Magica can be streamed on Netflix, Funimation, Crunchyroll, and probably the Moon too. The sequel movie, Rebellion, can be purchased on DVD/Bluray.

- Film Review: All You Need Is Kill - 01.15.2026

- First Impression: Kaya-chan isn’t Scary - 01.11.2026

- First Impression: Dead Account - 01.10.2026

This post was just amazing. Thank you.

Thank you so much! 😀

[…] Is Homura Evil? Or, What Homura Taught Me About Humanity […]

[…] of her transcendent state. Madoka was never meant to be God. And when she tried to save the world, she ended up a depersonalized concept and not the relational savior that Homura and the other magical girls needed; that humanity […]

[…] What I learned from Madoka was not what you might expect. True, the Messianic parallels are pretty strong in episode 12, but so too are the Buddhist threads, and I think I was equally struck by all that is not Christlike with that episode—by which I mean not so much Madoka’s wish itself, which is full of grace, but the way it transforms her into a transcendent concept, distant from the world and forgotten by it (I’ll explore the controversial implications of this, as played out in the sequel movie, Rebellion, in my post tomorrow). […]

[…] Is Homura Evil? Or, What Homura Taught Me About Humanity […]

[…] wait for the final film in the OG series (out sometime this year or next?) and a proper ending for Homura. And maybe Sayaka, Kyoko and Mami too. It’s never too late in the world of Madoka after all, […]

Hi Claire,

I accidentally found this blog looking for Madoka/MagiReco commentary today. I was not expecting to find such an in-depth Christian reading on the show and its themes, but you and Twwk do an excellent job making me think about my favorite anime from another perspective!

Hello Christopher! Thanks for dropping a comment, that’s so cool to hear! I’m glad you’ve enjoyed our posts. We are huge fans of the series and could definitely keep plumbing its depths for years to come! The final film can’t come too soon, right?

[…] thing in my mind—it was the ambivalence, the vast swathes of grey, the dialogue and imagery that demanded that viewers interpret for themselves what was going on and why, that makes Rebellion such a shocking and rewarding watch. I’m also not keen on the changes to […]

[…] even though they were often what we asked for. Instead, what we needed, what we longed for, was relationship with our God and connection with the One who created us; to know and be known—the gift of God himself! We […]