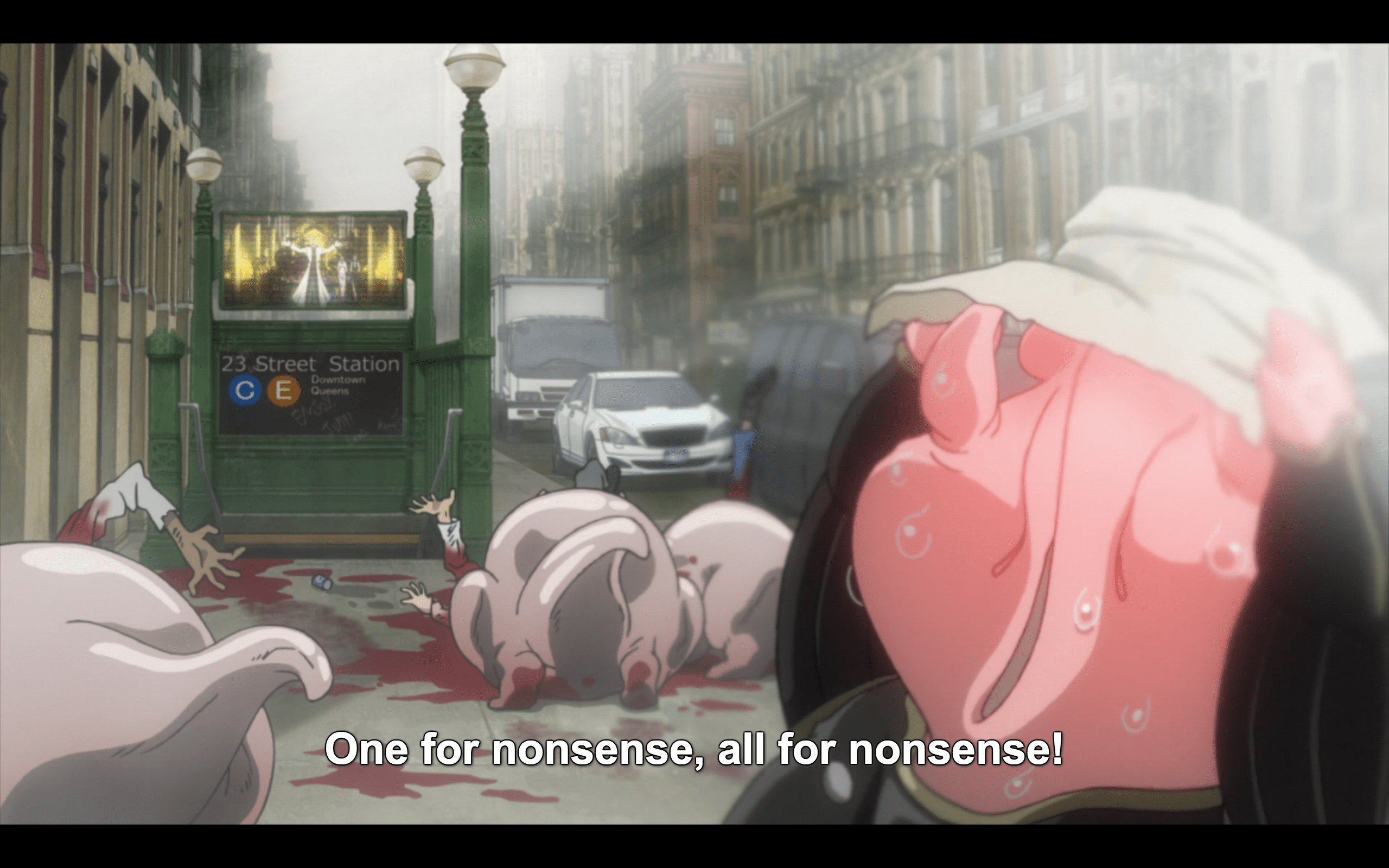

Cthullu has come and gone, and now it’s summer in the city. Young Leonardo Watch wanders through the crowded streets of Hellsalem’s Lot (formerly New York), which some years ago experienced a sudden and catastrophic erruption from the “other side” and amidst great destruction, was invaded by all sorts of horrors, magic, strange creatures, aliens, nefarious villains, vampires, and powerful inhuman lords of the abyss, while some humans changed in unusual ways, too.

But, well, it all sort of worked out.

Most of the visitors became integrated in NYC, the people there became more or less accustomed to them, there was a deal with the U.S. government that gave the city a sort of WWII Vienna status, and here we are. Sometimes, horrible things happen, but they are mostly kept in check by the armored police and the supe-rpowered and secret Libra organization. Mostly, life goes on as usual.

As with some other commentators, including Medieval Otaku, I found Kekkai Sensen (Blood Blockade Battlefront) ultimately disappointing on many fronts. It’s a frustrating show, so full of potential, great concepts, clever ideas, and an imagined world that was strangely fitting to great characters who could shine so much if the plot just let them. So many compelling conflicts were left behind for the fights and the ahem, non-euclidean plot. The comedy had moments of brilliance and episodes that were not so brilliant. The fanservice and lewd jokes were as gross as Nyarlathotep of the Bloody Tongue, but perhaps the biggest problem was that the heroic themes and the existentialist dark comedy were often in open contradiction. Do these people care for all those innocents dying left and right, or are they cool about it? What should I feel, then?

But, there were a couple of things that I liked a lot.

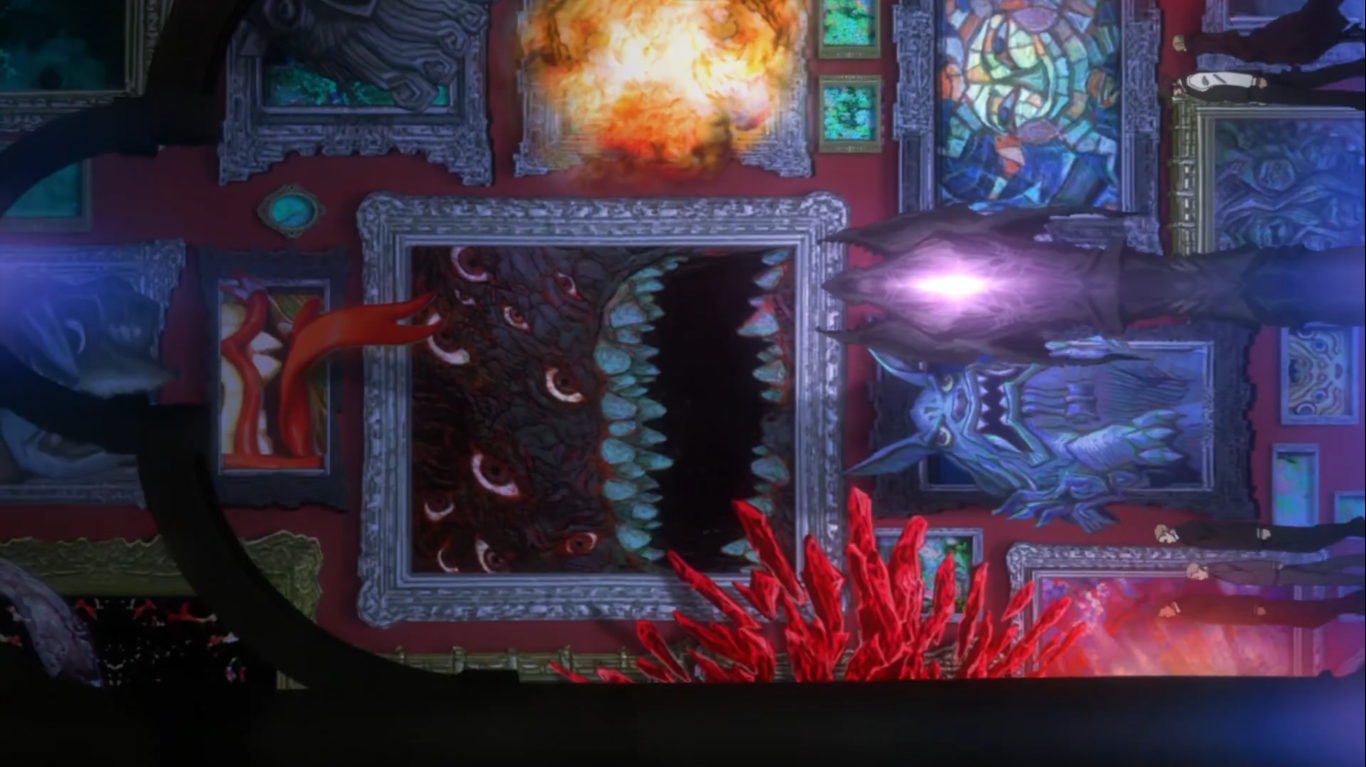

As ridiculous as it may seem, the central concept was brilliant. Why does it work? There is certainly something Lovecraftian about great cities, from NYC to Tokyo to Jerusalem to Rome to Madrid, side by side with their unique light, made manifest in so many small moments. People who see that light in the distance and come to seek opportunities and a future may end up scarred, bitter, and deformed, suffering alone, harming others, or screaming for attention in a sea of voices. Nature is far off. And it’s often quite like Babel, a place where you will not be found.

Simultaneously, great cities are also what they seem—that is, marvelous places of wonders and encounters, of monuments and cathedrals, standing side by side with hundreds of thousands of stories in which the human condition shines in a myriad different colors, where you may learn something new everyday and all those voices may also be a choir. In the beginning, there was Eden. And in the end, there will be a celestial city.

Maybe because of this, when the city betrays our hopes, the pain is so crushing—a sort of dull horror.

You may have heard of novelist David Foster Wallace (from Ithaca, New York), the author of an unfinished novel called The Pale King. I have yet to read it, but I know that, while the name may suggest the proto-Lovecraftian King in Yellow of R.W. Chambers, it is actually about the life of some employees of the Internal Revenue Service. And yet, it more deeply is about “the great transcendent horror,” “the deeper type of pain that is always there, if only in an ambient low-level way, and which most of us spend nearly all of our time and energy trying to distract ourselves from,” the “crushing boredom.” “Hellsalem’s Lot” echoes “the Jerusalem of Hell.” There’s something funny yet horrifying in the idea that the Cthullu monsters that represent cosmic, existential horror of a Cosmos where the Christian concepts are changed for primal, demi-conscious aberrations out of a nightmare, could be absorbed by the life at the city and become part of its rhythm.

The pilgrims of the Middle Ages coined the phrase “Roma veduta, Fede perduta” to allude to the crisis of faith sometimes experienced after visiting Rome. Not only because of the scandals of Christians and even shepherds, as, sadly, happens in a lot of places, but also because of the cruel disappointment that life is still so dull.

There’s something horrifying, too, in the thought that Jesus Christ would be killed near the great city over which He had cried, that He had visited every year in pilgrimage, the city of David, the city He had walked for three days at twelve, the city whose heart was the Temple of God. Don’t misunderstand, there are monsters in the peaceful countryside, too. The Galileans from Nazareth, who had known His family since He was a child, tried to execute Him just as much. But existential horror may be clearer in the supposed top of the world, where you hear a myriad voices at once, and there is so much pain in them.

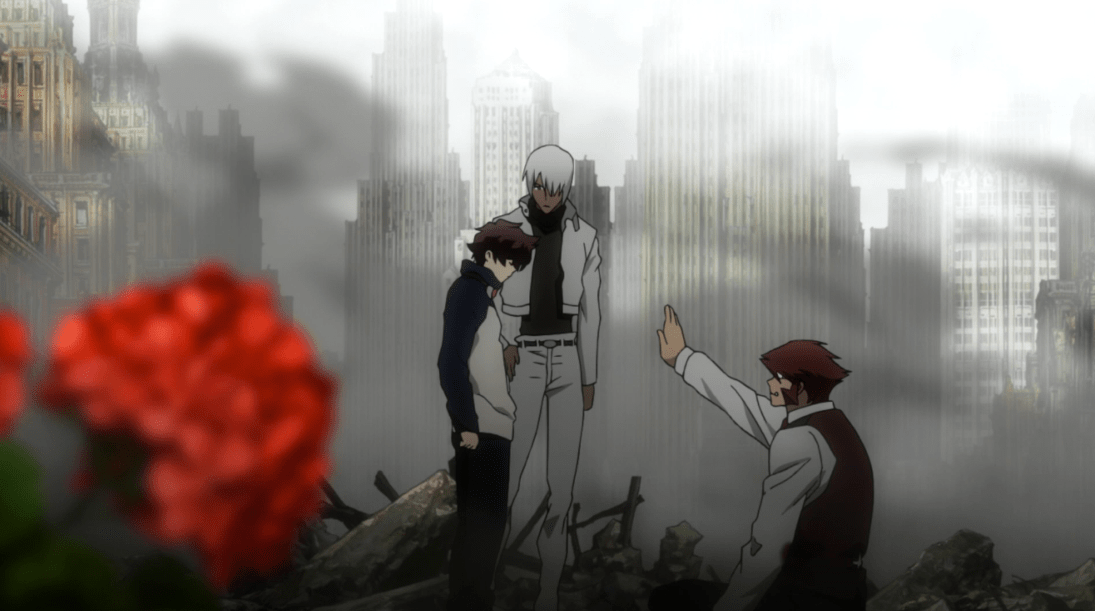

So, when the non-Euclidean plot of Kekkai Sensen starts becoming darker, and Leonardo Watch starts to feel more and more the weight of the city, I was not surprised. Honestly, his life, as the life of all the Libra members but two, felt pretty depressing despite all the (mostly-easy) victories and the jokes.

The Lovecraftian darkness was just beneath the bright surface. Films like, say, Akira, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, The Third man, The Dark Knight or the recent Joker explore this intersection between daily city life and monstrous horror just one alley away. You could argue that the entirety of the Batman mythos is deeply embedded in this theme—the luminous potential and the twisted branches, the existential tragedies, of the great city. And, back to Kekkai Sensen, when the darkness strikes, when the loneliness and the horror come to light, these people are all quite alone. Minor spoilers ahead.

Zapp Renfro wants to be strong, but lacks self-control. He burns his money as soon as he gets it, is often petty and abrasive, and spends his free time in an unending quest of unfulfilling sexual conquests. We see him burning his fingers. There’s a chapter in which his Master says that despite his hard training, he “has become a garbage pile.” It is played for laughs, as is the fact that he cannot overcome the test of the Master without an appeal to his appetites, but there is something sad about it.

Chain’s ability to disappear is not only a superpower. She likes jokes, but is not the one for direct interaction. Steven is alone in the dark after his luxurious attic party. Luciana Estevez works, and works, and works. Zed O’Brien once talked with his creator about poetry and music, art and science, philosophy and astronomy, but not anymore. Dog Hummer may go out of prison to visit an art gallery sometime. And… “Don’t promise him you will go if you will not,” says K.K.’s oldest son about her youngest. “I’m accustomed to it, but he is not”.

The NYC of Kekkai Sensen has two hearts. There is the Lovecraftian void from where the vampires come, which promises endless horrors and fights. There are the ruins of a Cathedral, where lonely people go to think. The forgotten city of God, perhaps. It is destroyed. In Jerusalem, the Temple is no more. The balance tilts towards the shadow.

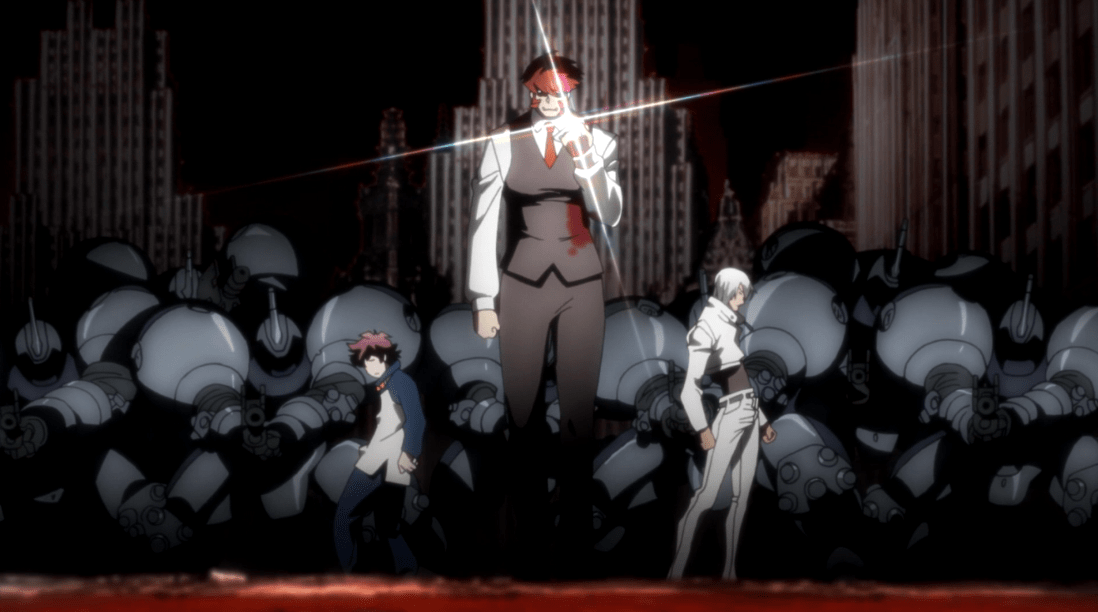

But having mentioned Batman, and not having mentioned Klaus von Reinhartz, the leader of Libra, you probably guess where I’m going with all this. You see, in Hellsalem’s Lot there is a man who risks his life daily respecting a code, determined not to become a vampire who sucks the blood of others. He is awkward, rigid and somehow timid, and while he can win some battles, defend some people here and there, he is currently powerless to turn the tide of the city, or even his group. Zapp’s Master rightly deems him an inexperienced leader, blaming him for his pupil’s lack of discipline. But he is the one who humbly asks the Master to spare him. He will fight to defend Zapp, but not against his victims when they demand justice. And so, Zapp trusts him and respects him. He constantly tries to beat him in a fight, but never manages to do it. Klaus fights him back without anger, and he keeps trying.

Steven is his friend, and when he unleashes his dark side, it’s in his absence. He remarks that Libra’s leader would never allow what is going to happen. He is courteous with Chain and K.K., because he honors womanhood. “You are truly the only one who worries about me like this,” she says, and he, “…no matter how strong you are, you are still a lady.” He will silently spend a fortune of Libra’s budget so Zed can be with the rest, providing him with the apparatus he needs to breath outside the water. He arranges Hummer’s visits to the art gallery. And among the members of Libra, it is he in particular who becomes the inspiration for Leo, whose little sister—now in wheelchair—used to call him her “knight” and who is heartbroken because, paralyzed by fear, he let her be harmed. For Klaus, the world of Hellsalem’s Lot is not a dark comedy. He shows respect to the police and the warden of the prison and the authorities, and cooperates with them.

Klaus fights vampires and other creatures with his mind, with powerful crosses made of his own blood, and also, with the help of his allies, employees of Libra, and, more rarely, some discreet and powerful servants of his family. He is manly, disciplined, righteous, humble, discreet, sometimes tender. In a word, he is chivalrous. Chivalry in NYC.

Visually, Klaus resembles X-Men’s Beast, with his contrary traits of fierceness and professor-like politeness. Narrative-wise, he is sort of a mismash of Dracula, Van Helsing and Batman (who has himself something of Dracula and Van Helsing). If you check his manga background (manga spoilers), he is the victim of a vampire attack whose curse was sealed away in a giant stone crucifix at level 12. At level 13, he would become a Blood Breed, and a threat to those around him. So, his story is one of earned self-control, of developing and taming a powerful energy which could turn him into a beast, and turning it into a power for good, for humble service, for saving others. Like Bruce Wayne, he is the eldest of his noble family, and a man with a legacy to honor and loyal servants towards whom he shows gratitude. He shows respect to ‘Lucky’ Abrams, his master, whom everybody avoids due to the horrible luck he brings, and is calm, polite, and fierce in battle.

He has an absurd level of power and intelligence, as most people in this show, but more interestingly, unlike Zepp or Chain, he won’t use it to show off or gain revenge, but strictly to protect, another Batman feature.

I especially admire the mercy he displays in “his” first episode, which is episode three. I think no other character in the show, except Leonardo himself, displays such a feature. Against some other Van Helsing analogues (or caricatures), he is not a gun-happy zealot. He shows respect even to the Lovecraftian horrors, and negotiates with them when it is necessary to protect others, even those not especially worthy. He accepts many less-than-ideal situations with patience and realism. And, even more (I kid you not), in the same way as in Uhiro Nightow’s original one-shot manga, Pilot, he is revealed to be working, as Van Helsing himself, for… the Vatican! At this point, you won’t probably be surprised to learn that Klaus is not only an aspirational character for Leonardo and Zapp, but for me, too.

I find something deeply hopeful in the way Klaus fights. Our Lord told us not to remove the straw from the eye of others without removing the beam from ours at the same time. Here, Libra’s leader fights vampirism in himself and others at the same time. He fights mainly with truth and personal sacrifice, learning and using the true name of those he fights, and with his own blood imitating as he can the cross of Christ, from which all salvation comes.

His life as a warrior is a lifestyle, and he will ally himself with whatever is good in those around him, as a patient witness of what is true and good. He is one of them, and at the same time his ways are often different. We should also fight like that. With the weapons of truth, calling the evils by their true name, and by imitating Christ with our own loving sacrifice, knowing that we have received a mission, that we are the Church, and counting on others. Klaus often gets to know the name of his enemy by the prophetic gift of Leo.

Another remarkable feature is his patience. The virtue of fortitude is made manifest sometimes in attack, but more often by resisting. When Ulchenko is going to confront Don Arlelle, Klaus advises him to know his limits and avoid trying to get the checkmate, setting his mind in resisting until the game ends instead. Some vampires cannot be defeated right away. And some opponents are opponents others must face. He is a man who is eager to buy time by humbly doing what he can, and so he can fight opponents who represent despair, monomania or depravation, little by little. He knows he is inexperienced and too rigid, and is learning from his friends, trying to grow while keeping his unique way to do things, which is grounded in deep truths. Zapp tricks him to enter a fight competition for various reasons, not all altruistic, but one of them is. He knows he will enjoy himself, as he does. In time, he will probably be able to keep his ideals and discipline, but relax a little.

The show is, I think, clearly not as hopeful in matters of theology as Klaus is. The empty, destroyed cathedrals and the Lovecraftian symbols, as well as the existentialist themes, point to a world without a Christian center, in which the more secular hope which motivates Leo is the new center. “There are no Gods, but we don’t need them/ Even if they were…”, says the second opening. The final episode seems to include Our Lord’s Passion and St. Joan D’Arc execution as signs of despair, more than the signs of transcendent, burning, horizontal hope they are in my own life. Mary Macbeth comments with grief how, twenty centuries after the coming of Christ, people keep distrusting and killing each other. For Leo and the show, not unlike the Old Pagans, we are dragged by primal forces and illuminated by the flickering candle of our own heroism.

Leo, nevertheless, will find a powerful appeal, a deep calling, in the heroism of Klaus, founded in transcendent hope. Christ considered the sufferings and tribulations of the Cross necessary, and chose them. “No one takes my life away from me. I give it up of my own free will. I have the right to give it up, and I have the right to get it back.”

I believe that our own flickering candles may be ignited with a more powerful fire, one not of this world. Christ told His disciples that the Church is the salt of the Earth, the light of the world. It is not to be hidden, but to shine like a city in a hill. “You shine,” as the Apostles told afterwards to the Christian people, “bright like lighters of the world, showing a reason to live.” The Temple may be no more, but we have Christ, who is Himself the Temple. He is present in Heaven, in the Eucharist, in his Word, in the poor, in the infused charity and infused faith of the Church, in the churches and places in which we pray. The future New Jerusalem will have no Temple and no Sun: His Temple and His Light is Christ. One day, the true King will ride in triumph once more in the streets of Jerusalem, no more Hellsalem.

So maybe the wonder is not so much that people are still sinners two millennia after Christianity, but how the light and hope of Christianity remain through all ages, the cross still standing while the world turns.

While there are many ways, paths and ideals in the City of God, I have always found the ideals of chivalry and knighthood very useful to grow and be more like the patriarchs or St. Joseph, who according to Pope Francis, “appears as a strong and courageous man, a working man, yet in his heart we see great tenderness, which is not the virtue of the weak but rather a sign of strength of spirit and a capacity for concern, for compassion, for genuine openness to others, for love.” God is certainly chivalrous and heroic in that sense, powerful, delicate and just. Jesus Christ, unlike Klaus, is not awkward or rigid at all. He, like Leo, came from a small town to a bigger city, Capernaum, and visited at least once a year a bigger city, Jerusalem, and is remarkably free, and an expert in creating chances, encounters, in approaching everyone at his or her own pace to bring that person into His plan of salvation. He is more like Kyousuke Natsume. Klaus may still grow, nearer to Him while fully himself. Maybe Cthullu has come and gone, and hope remains.

This year I’m 28, like Klaus. May God help me, too, grow in strength, wisdom, and grace like an oak tree, my roots in Christ, my candle burning, and willing to fight for justice. And may He bless us all. Hello, world! Here we go.

Kekkai Sensen/Blood Blockade Battlefront is available in Crunchyroll.

- A Tale of Two Alchemists, II: The Brotherhood of Everything - 04.22.2024

- First Impression: YATAGARASU: The Raven Does Not Choose Its Master - 04.15.2024

- First Impression: Viral Hit - 04.10.2024

[…] own mind,” fearing that Johan may be right. As for now, we are in the confused world of, say, Blood Bloackade Battlefront, and not in the one of, say, Now and then, here and […]