We don’t always need an epic character arc. Not in anime, and not in real life. Sometimes, it’s the smallest of steps that transforms a life. At its heart, despite all the fantastical creatures, stunning scenery and heroic destinies of an isekai adventure, this is what The Wonderland is about: the minor, muted act of taking a single step, of eyes opening to the beauty of the world, and in so doing, of finding the courage to mend a mistake.

Akane and Chii-chan are in for an adventure!

The Wonderland follows teenager Akane as she and shop-owner Chii-chan are invited on a journey to a mirror world by a mustachioed alchemist, Hippocrates, and his diminutive magical assistant, Pipo. All is not well in this wonderland though. The failure of the land’s prince to complete an important ritual has left the realm on the brink of drought. Akane, whom Hippocrates greets as the long-awaited Goddess of the Green Winds, is expected to rescue the Prince and enable him to complete the ritual, releasing water and life once again throughout the world. Akane is not terribly enthused about her intended mythic role, but sets off reluctantly through the trap door in the shop floor to the grandiose adventure that awaits. (Starting with an encounter with a very large pink bird.)

But the real story that underpins this fantastical journey is a much more modest one. And one of much greater significance for normal Earth-bound folk like you and me. You see, Akane is feeling guilty—and she doesn’t know how to deal with it.

The film opens with her complaint that she is “moping in this nice weather like an idiot.” Her entire reality is colored not by her beautiful surroundings or the lovely summer day, nor by her mother’s love or the feline displays of affection from her tuxedo cat Gorobeh, who shoves his furry butt in her face (typical); but by her guilt and the suffocating discomfort it has wrapped her up in.

At school the day before, her group of four friends stone-walled one of their number, Mayuko, over a misunderstanding about coordinating hairpins. It was a small miscommunication that Akane could sympathize with, but chose not to. When her friend asked for Akane’s help in patching things up with the other three, Akane blanked her, too afraid to run the risk of rejection herself, presumably. As the film begins, she is faking illness so that she won’t have to go to school and face Mayuko, whose texts she’s also ignoring.

Akane has committed a “sin of omission”—she has failed to do an act of kindness. And although it is small enough that many would probably shrug it off, it is making her miserable.

So much so, that Akane’s guilt blinds her to her surroundings. She cannot see the profusion of flowers and the sea of brilliant colors with which her home is awash, both inside and out. (She even tells the prince later that her world lacks color and the beauty of nature!) She cannot recognize the garden that her mother so faithfully cultivates, or the life-giving home she provides, instead dismissing her mom as a mere housewife who has it easy. Akane is oblivious to the love and loveliness around her.

As a result, she cannot receive it or let it in. Even when her mother, Midori, prepares a veritable feast for her, she is too self-conscious to acknowledge the gratuitous generosity being extended to her. She stays firmly put in her grieved state, grumbling and whining when her mother asks her to run a simple errand. She is in a bad mood and she will fight tooth and nail to hold onto it.

Akane’s home. I mean, if she doesn’t appreciate it, I’d be happy to move in…

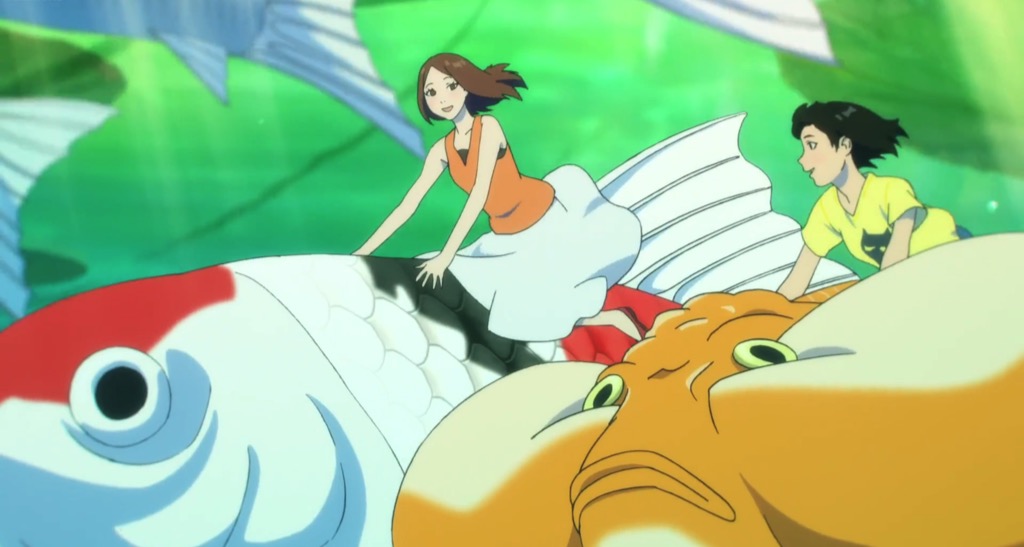

Akane carries her bad mood with her into the wonderland, her guilt weighing heavily on her throughout the film. We know this partly because it takes such a long time for her bad mood to lift, but mostly because, at the height of the wonder when she’s finally beginning to enjoy herself, she makes a small gesture that reveals what is on her mind: She picks up several heart-shaped pink shells—collecting enough for each of her friends and herself. Akane has just discovered that she can breathe under water and is alternately dodging and riding the giant koi in a dream come to life, yet in the middle of it all, she stoops down to search out those shells. Might this new little item shared among the friends heal the discord caused by the hairpins? Might this small gift make up for her silence before?

The dark cloud does lift from Akane eventually, and pivotal in this shift is a gift from Hippocrates: an anchor necklace that he has imbued with magical power. It is this token that propels Akane into her otherworldly identity as the Goddess of the Green Wind, or as it transpires, her identity as her mother’s daughter, since the original Goddess is Midori (whose name means “green”). The necklace marks out Akane’s true identity as royalty, the daughter of a Goddess and made in the image of the divine herself—an identity that she is determined to deny.

When Akane is feeling particularly negative and hopeless, the anchor becomes heavier, pulling her forward into action, or compelling her to stand firmly in place in the face of fear instead of running away—occasionally to comedic effect! The anchor draws her toward her destiny, even though it is a much grander role than she ever would have chosen for herself. At one point, when the anchor freezes her in the path of an oncoming tank driven by the villainous Zan Gu, it is actually orchestrating her collision with her world-changing destiny, namely, to encounter Zan Gu who is in fact the Prince she must help. Recognizing him and his fear and anger is what leads Akane into a place of compassion, which sets her free from her own “negative feelings.”

You’ve probably guessed by now the biblical image that Akane’s necklace reminds me of. “We have this hope,” explains the writer of Hebrews, “a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul…” (6:19). If we read the rest of the passage, we find that it’s a hope that gives us access to where Jesus himself is, the holy of holies, where in Old Testament times only the high priest could go, and then only once a year and after a great many cleansing rituals, lest he die in the presence of God’s holiness. It’s a hope that is founded on God’s promises and his constancy, his reliability, and the fact that he will fulfill all his promises, even those that seem unbelievable. It other words, the anchor for our souls is the hope that gives us a new identity—”righteous” and “able to approach God”—and leads us into places we could not go on our own, all because of whose children we are.

Don’t you wish sometimes that relationship with Jesus and knowledge of the word of God worked like Akane’s anchor necklace? That we would simply feel compelled to be hopeful, to do the right thing, to be courageous? That it would magically propel us on the path of our destiny? I know I do.

But as the film closes, Hippocrates reveals that the necklace wasn’t actually the source of Akane’s courage after all, at least not after that first little while. The effects of the necklace wore off quickly so that it was instead up to the heart of the wearer to take those bold actions, walking in hope because they chose that path, consciously or unconsciously. In other words, the necklace gave Akane a much needed push at first, but then it was up to her to embrace a new way of doing things, to make living courageously a habit and hope a lifestyle.

Now that’s much more like how the journey of faith works, isn’t it? That’s what makes Akane’s emotional arc in this film such an encouragement for us too.

There is another story of struggle in The Wonderland as well, that of the Prince. His destiny is to carry out the drop cutting ceremony, where he must incite an ancient well to erupt with water and then cut the droplets with a sword to release the life-giving water into the land. If he fails, his life is forfeit. And therein lies the heart of his debacle: He is afraid to fail, and in failing, lose his life.

There are some strong parallels here to the living waters of the Bible, that is, the waters that symbolize Holy Spirit, and the story of how it came to be that God’s very own Spirit could become a well of spiritual water in each of us.

In The Wonderland, the flow of the water to all the land is reliant on the Prince, and more to the point, on his willingness to lay down his life in order to release the life-giving rains. Just so was the full release of Holy Spirit reliant on the sacrifice of the King’s Son, Jesus, and the test he took on Calvary.

The film’s Prince is afraid of the test and seeks an alternate path, deciding to destroy the well itself and the source of his fear. Pretty relatable, right? He loses his humanity along the way and turns into a monstrous metallic skeleton in his quest to avoid the risk of sacrifice required of him. He is rebellious and relies on the dark arts in his attempt to destroy the path before him, to raze to the ground and destroy the well, the symbol—like the cross—of the cost of saving his people. In his rebellion, he chooses death not just for himself, but for his entire realm.

That is, until Akane reaches out to him and fills him with the courage he needs to face what is to him an instrument of torture, the empty well. How does she manage this?

The stakes in Akane’s classroom drama are nothing like those faced by the Prince of the mirror world, and yet she is able to empathize with him and articulate his fear for him because it is also, at its root, what she has been struggling with too: the fear of risking her social life by standing up for her friend; the fear of failing to rescue her friend, to release life and healing into the situation of broken, dying relationships. She is afraid of not being able to save her friend, and so she does not try.

So it is too with the Prince, Akane realizes. He was afraid of failing the ceremony, and so he refused to try. But whereas the Prince was bent on destroying the whole scenario, Akane’s preferred coping mechanism was avoidance. She hid under her covers. This is the real reason why she was unable to receive the delicious meal from her mother properly, and why she resisted her mother’s errand to visit Chii-chan and pick up her birthday present: she was trying to hide and all her mother was doing was seeing her and forcing her to let herself be seen by others. And it made Akane angry.

Did you know that scripture actually encourages us to hide? There’s a phrase that recurs throughout the Psalms, “take refuge.” But translated more fully, it means “turn and hide”.

Hiding is not the coward’s route. Not in and of itself. The problem is when we hide in the wrong things—things that won’t protect us and encourage us in our vulnerability, but will instead simply distract us or carry us away into an escapist fantasy. No, God invites us to hide when we are feeling weak, but specifically to hide in him. It’s ok to escape from overwhelming situations to catch our breath—but we need to do it in his arms, where he can whisper us full of courage and purpose and true identity.

This is what happens for Akane in the wonderland. And it is what she does in turn, in her own awkward way, for Zan Gu. She holds him—just barely, clutching his ankle—and she sympathizes with him in his fear. But she also calls him to be the Prince that he is, the Prince he was born to be, offering her aid and accompaniment as he faces the well. The Prince has been running this whole time, but Akane catches him up in his hiddenness, and walks him out of it. She stays with him even to the point of falling down the well together with him, seemingly to the point of death. She is there when he survives, and when he carries out his own small act of grand significance, the drop cutting ceremony.

When the well finally erupts, the geyser of life-giving water must be met with the sword; it takes the water and the sword combined in order to release life, which takes the form of waves of dove-like birds. As the Prince—once frightened, but now filled with courage; once an agent of destruction, but now a source of life—cuts the droplets of water, life literally takes flight and forms into clouds of rain and snow that nourish the whole land.

In this way too the meeting of the water of the Holy Spirit with the sword of the Word of God releases life across our land, in our homes, schools, offices, communities and nations. What a beautiful picture of the act of intercession, that sacrifice of prayer that brings together the Spirit and the Word for the sake of the world! Often, different bodies within the church can tend towards emphasizing the importance of one over the other, of Spirit or Word; but the fullness of life requires that we read the Word in and with the Holy Spirit, and follow the Holy Spirit with the Word in hand and written on our hearts. The fullness of life is in the meeting of the water and the sword.

In witnessing all of this and opening her eyes to the beauty of the wonderland, and her heart to empathize with someone else’s struggle, Akane is transformed. When she supports the Prince in facing his fears, she learns that she can do the same: she can walk herself out of her hiding and step into her identity as a true friend to that ostracized girl at school. Her magical adventure in a parallel world plants in Akane a tiny seed of courage—mustard seed-sized, perhaps—but it is enough to enable her to set right her sin of omission, and thereby change the life of a friend.

During the closing credits, Akane gifts the first of the pink heart-shaped shells to Mayuko, the friend she let down, and then to each of the others. When the others come over to greet Akane, Mayuko hunches her shoulders protectively and retreats into herself, as the others ignore her. But then Akane looks her in the eyes and draws her into the conversation, requiring the other girls to include Mayuko as well. That’s all it takes to undo the estrangement.

Akane finally braves her fear and repairs the broken bridge between her friends, making amends for the guilt she has carried all this time. How fitting that this reconciliation comes through a gift and a moment of shared beauty, exclaiming over the delicate shells and the affection they represent. Her entire adventure in the wonderland was a gift, after all—a birthday gift set into motion by her knowing mother—and a gift that enabled Akane to see beauty once again.

Akane’s arc is not dramatic; it’s not epic. It’s even a little awkward in how very understated it is. It is easily missed. But it’s enough—just a tiny nudge by a necklace and a small realization that prompts a hand extended in friendship. That’s all it takes to open Akane’s eyes so that she can see that her world is just as beautiful as the mirror world, and her friend, just as worthy of rescue as the Prince of the entire realm. It’s all she needs to see in herself the courage and compassion to mend an impossible, frightening situation for someone else, and in so doing, live more fully in beauty and wonder herself.

The Wonderland shows us that it’s not always a blazing epiphany that we need, or a grand, dramatic act of rescue that is needed from us. Sometimes it’s a small course correction that has us going back to clean up our mess; it’s taking up the ends of the snapped thread that runs between our heart and that of another and tying them together again. Sometimes, the grandest stories in life—repentance, transformation, reconciliation, salvation—pivot on something as small as a seashell.

The Wonderland can be rented on iTunes, Amazon Prime, etc.

- First Impression: Mysterious Disappearances - 04.11.2024

- First Impression: Go! Go! Loser Ranger! - 04.07.2024

- First Impression: The Fable - 04.07.2024

[…] film takes the popping color scheme of the studio’s earlier works like FLCL Progressive and The Wonderland, and turns the hue saturation up to 110%, electrifying the visuals like neon lights. The human eye […]

[…] god. Mkay. But studio Signal.MD has been really great to me this summer with the delightful films The Wonderland and Words Bubble Up Like Soda Pop (pardon the self-promotion links), so I will give this series a […]

[…] Well, perhaps you’d go mad, or fear that you already had. Perhaps you’d be terrified. Or perhaps you’d just scoff at the sheer absurdity of it all, refusing to acknowledge it. But perhaps (and I know that this is not the most usual response), you’d attentively consider the consequences for yourself and the Cosmos with a growing sense of amazement, of wonder. […]

[…] It’s mind-bending, isn’t it? The upside-down kingdom, where the small things can save the world. […]

[…] with its distinctive character and color designs in films like Words Bubble Up Like Soda Pop and The (Birthday) Wonderland. But it’s really the shadowy world of Mars Red or Science Saru’s ink-painting inspired The […]

[…] Ranking of Kings and Spy x Family, and the unique stylistics of Words Bubble Up Like Soda Pop, Birthday Wonderland, and Mars Red to their credit. This episode is dismal. Utterly dismal. Even setting aside the CG […]

[…] in the Mirror begins with this type of setup, familiar from director Keiichi Hara’s last film, The Wonderland, it quickly disrupts these predictable plot beats and instead, for most of the film, the Wishing […]