There are many lessons to learn from The Heike Story: the cost of pride, the trauma of war, the insidiousness of bitterness. Every episode conveys these truths with both the elegance and firmness of a martial artist’s killing blow. But the true heart of this series is far subtler and as such can be easily missed. At its heart, The Heike Story is a contemplation of the power of forgiveness.

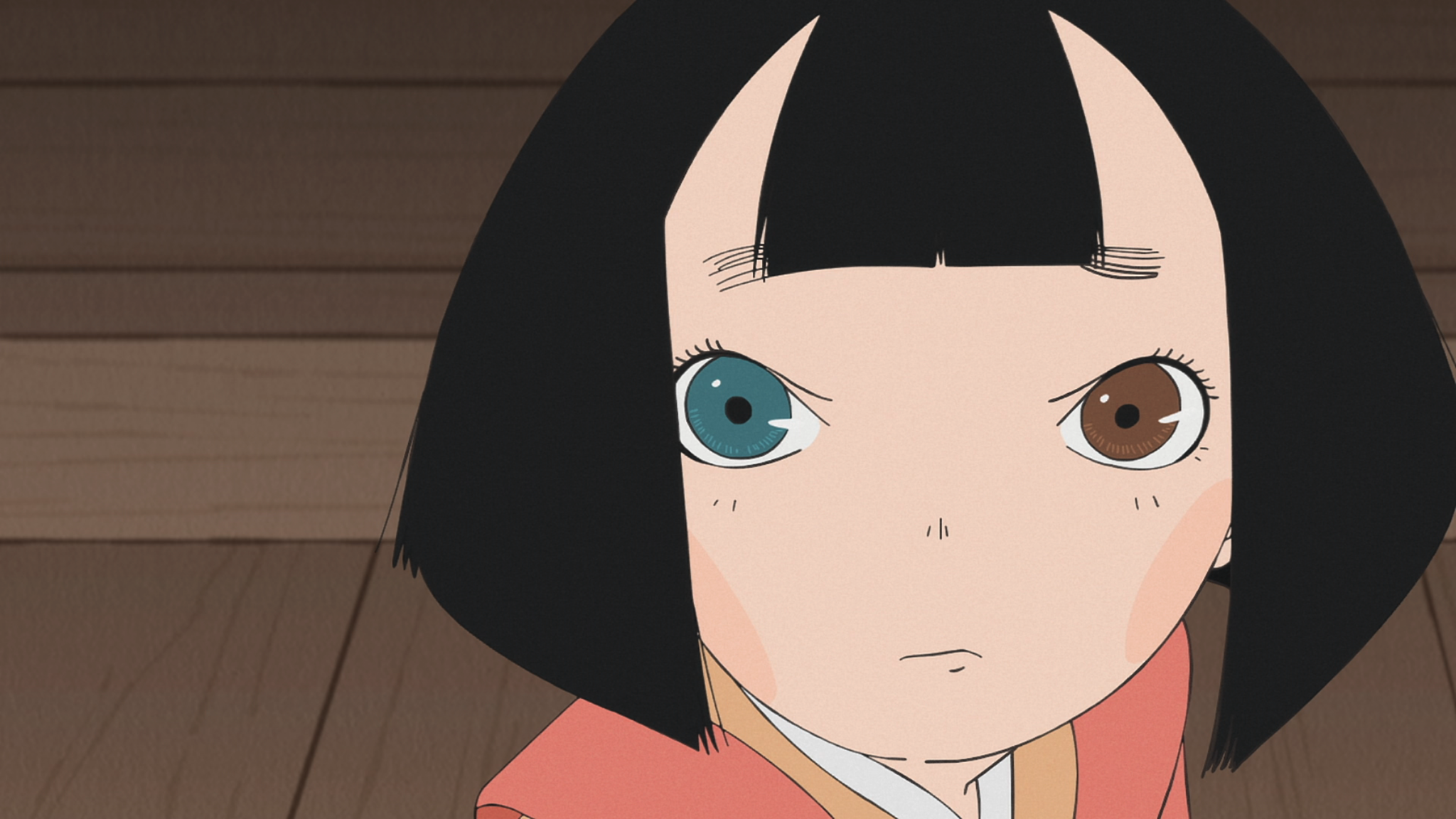

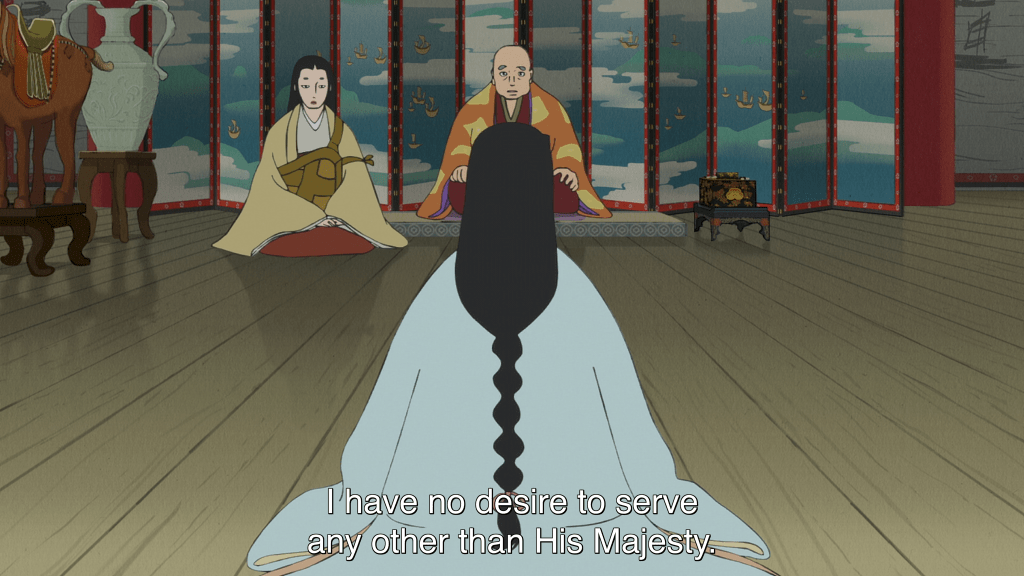

In this masterful tale of ambition, deception, and belligerence, it is those who forgive that wield the ability to redesign the world and redefine their place in it, producing a legacy more meaningful than the title of victor in some fleeting battle. First among these radicals is Tokuko, daughter of the Heike, wife of the Emperor, and Shigemori’s younger sister. She is also Biwa’s first friend. She lives a life of luxury, but also one dominated and defined by the political machinations of her father, Kiyomori, the head of the Heike clan. By the age of 16, she is married off to the boy-prince in line for the throne, so that she might eventually produce his legitimate heir and enable her father to monopolize the courtly government. Tokuko is but a pawn in life, and one that can never be queened.

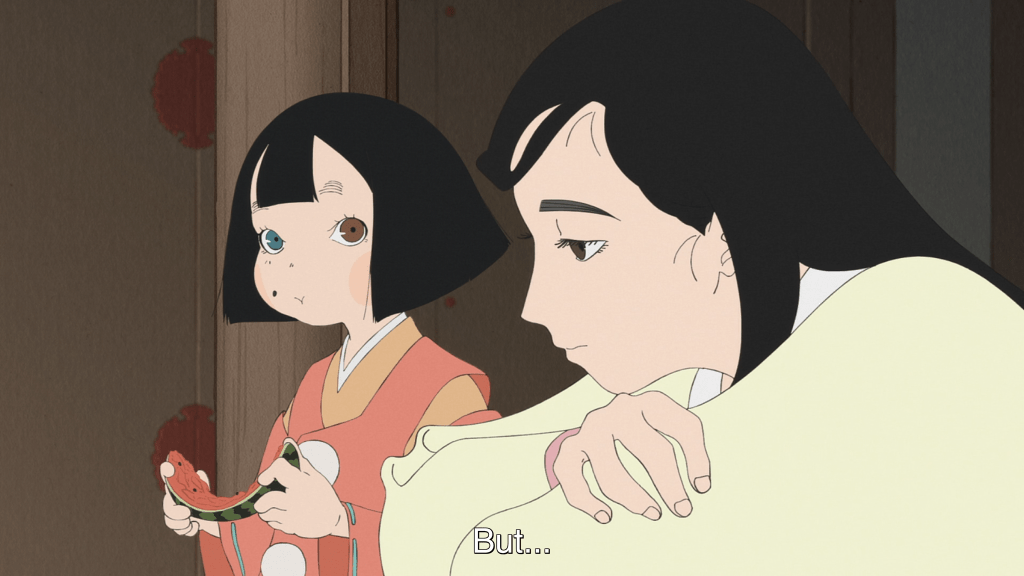

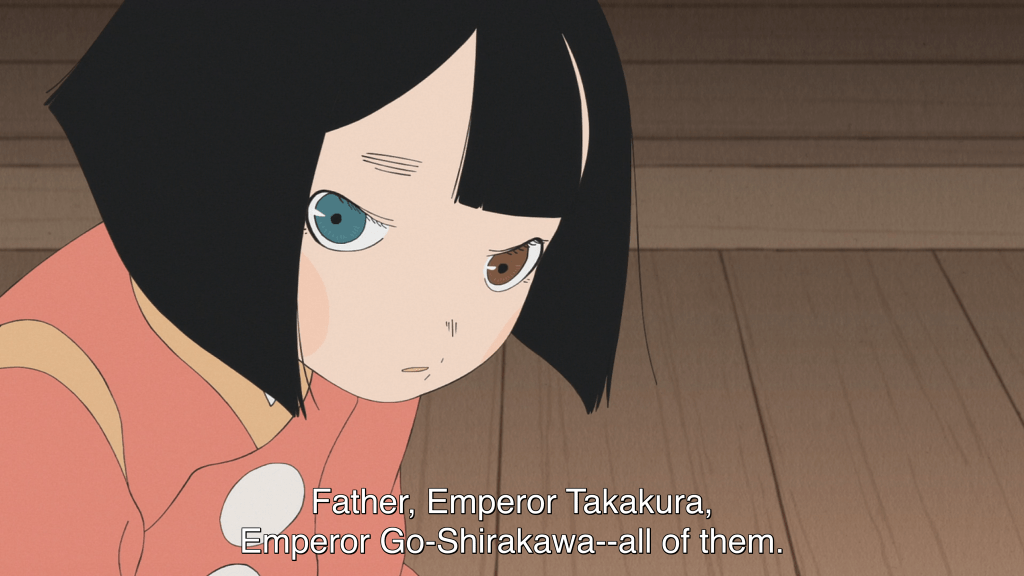

But something startling happens in episode five: Tokuko forgives. She forgives her father for his manipulative treatment of her; she forgives her husband, Emperor Takakura, who is unfaithful to her and abandons her; she forgives her father-in-law, Emperor Go-Shirakawa, who baits the Heike relentlessly. Tokuko forgives the men who ignore, isolate and use her as a pawn. But what’s incredible about this—and what rescues it from becoming merely another tale of feminine disempowerment—is Tokuko’s reasoning behind her decision to forgive.

You may have heard the saying from Joyce Meyer that unforgiveness is like drinking poison hoping that it hurts your enemy, the one who has wronged you. Hits pretty hard, right? Personally, I have found this insight to be very helpful in motivating me to let go of resentment and offense and instead pursue forgiveness.

But it isn’t always enough. Because we human beings have this incredible ability to gradually build up our tolerance for poisons, don’t we? Both literally and figuratively. Throughout history, rulers and elites have dosed themselves with small quantities of poisons to protect against assassination (also known as mithridatism). There have even been times when poisons were ingested regularly by the wider population as well, in pursuit of clearer skin (just a tad of arsenic each day to get that healthy glow!), under “medical” advice (mercury as a treatment for everything from melancholy to constipation, syphilis to the flu, for example), or more accidentally, as with lead pipes and pencils.

And we’ve done it metaphorically for just as long. Sometimes, bitterness can become such a familiar taste in our mouths that we feel just fine downing its poison, and the prospect of giving it up is far more distasteful. Just as it can be challenging to adapt one’s diet or drinking habits, so too can giving up on a grudge be so difficult (and even painful!) that we question whether it’s really necessary. A habit of bitterness can feel comforting in its familiarity, like the flannel-warm embrace of pajamas after a long hard day. And if it isn’t hurting anyone else, well then, where’s the harm in that? Maybe it’s easier just to pay the cost.

But there’s more to the destructive power of unforgiveness beyond simply poisoning oneself. It also poisons the world around us and robs the world of the kind of possibility that can only be born of hope. After all, unforgiveness is a kind of hopelessness; a kind of giving up on a future that could ever be any different from this present that is scarred by the past.

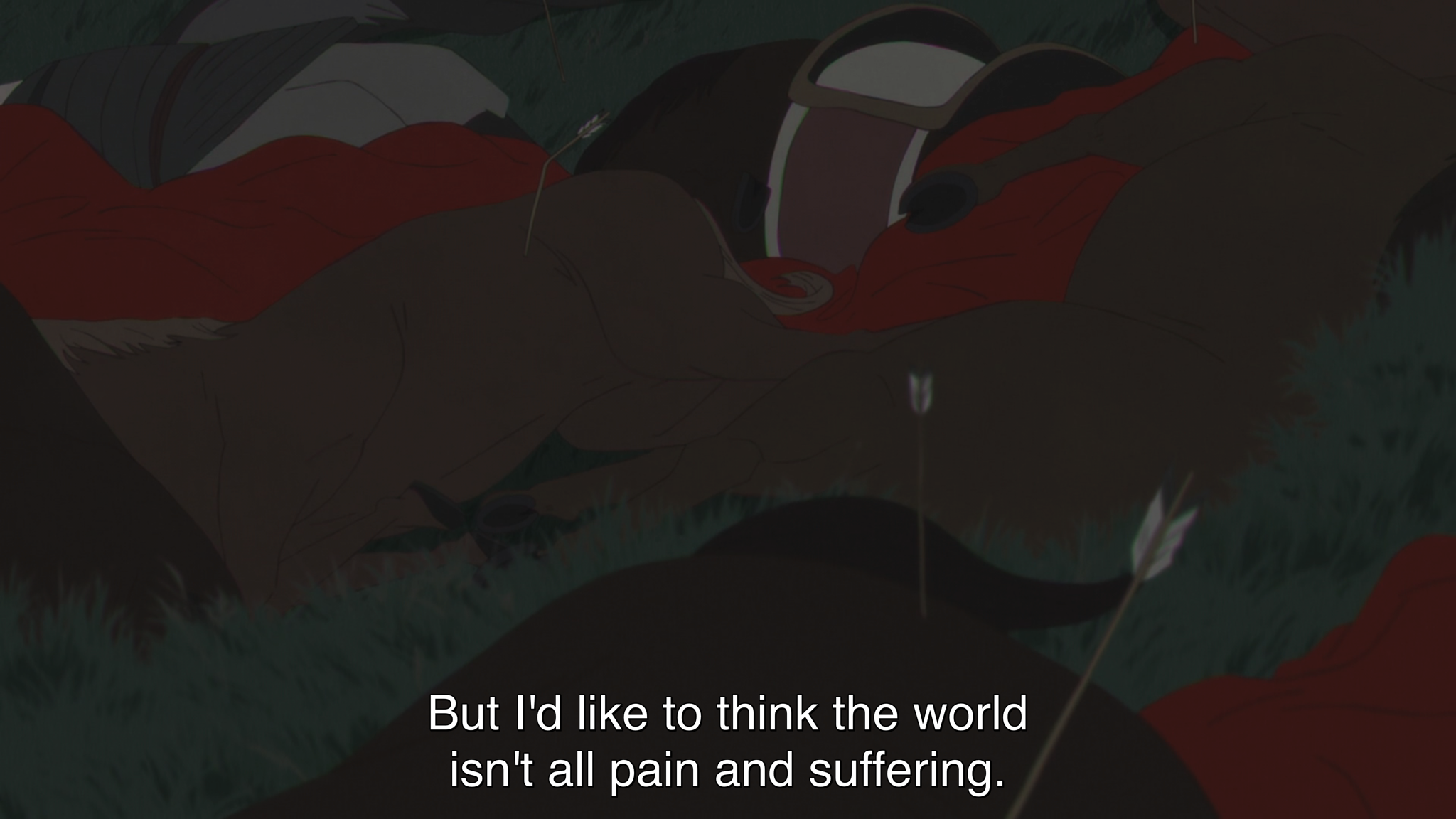

This, this is what motivates Tokuko to pursue forgiveness. She wants to believe in a world that can be defined by something other than hatred and conflict, pain and suffering; a world that is different from the one created by the warring Heike and Genji clans.

And so, she forgives.

The cost of forgiveness is visible in Tokuko’s tears…

Tokuko forgives in order to create the world anew; to inject the realm of what is possible on earth with something healing, something more life-giving than what she sees around her; to make it a better world for her infant son. She does not simply retreat to the monastery, though that is where she ultimately ends up; instead, she lingers long enough in the heart of the conflict to forgive first and leave a legacy of grace.

This simple act is powerful. Granted, it doesn’t bring about an end to the warring or save any lives. And in fact, it may seem to be merely a pleasant sentiment rather than a pivotal plot point in The Heike Story—a delicate flash of idealism that ultimately cannot shift the unrelenting arrogance of Kiyomori and Go-Shirakawa or the imperialist mindset that spawned them and their conflict. But as the rest of The Heike Story unfolds, this small moment of forgiveness proves to be the instigating event for both Tokuko’s own transformation and that of Biwa.

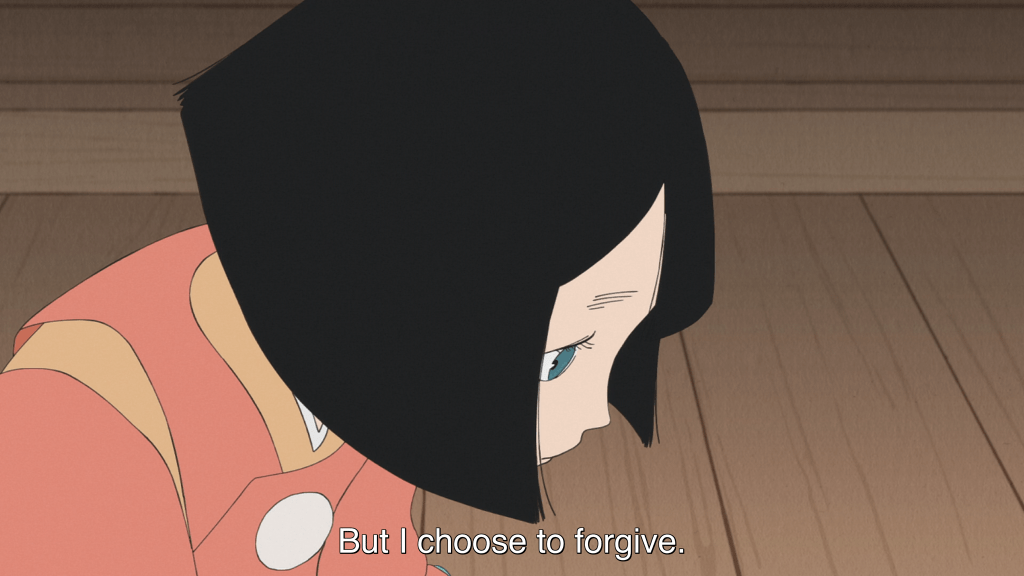

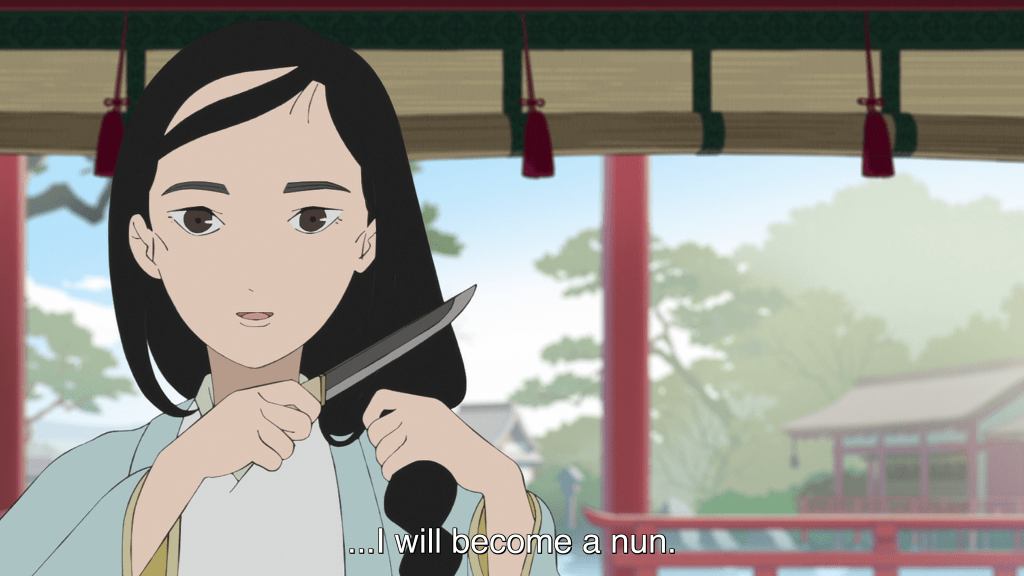

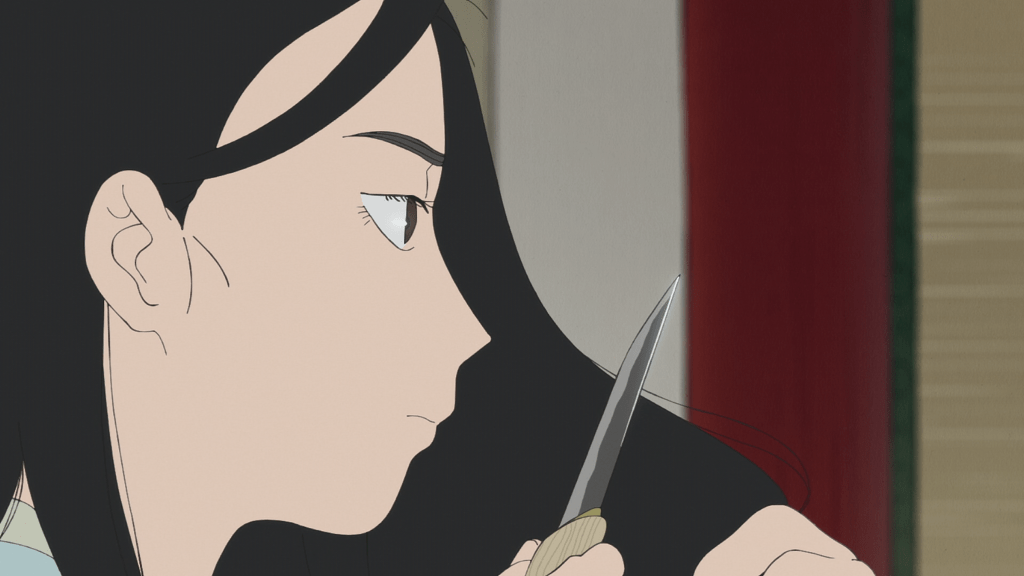

Forgiveness is an act that requires intent. For Tokuko, the act of forgiving introduces her to her own capacity for agency, for choosing her own actions, and it changes her life. Forgiving her father for his exploitative treatment of her empowers Tokuko to resist his subsequent attempts at manipulation. When she is widowed and Kiyomori schemes to marry her off to her father-in-law (!!), she refuses, vowing calmly to become a nun should he insist on her remarriage. Certainly, her scope for agency is constrained, yet having once chosen something as subversive—to the Heike at least—as forgiveness, Tokuko is emboldened to set aside the conformity that had previously kept her silent in the face of the dehumanizing “cultural norms” that dictated her life. By the end of the series, the only survivor of those who had wronged her, Go-Shirakawa, seeks Tokuko out to learn from her wisdom—and she is gracious enough to share it with him.

The order of things here is quite counter-intuitive to our contemporary culture, where usually we are encouraged to “stand up for ourselves” first, and then maybe, some distance down the road, consider extending forgiveness. Maybe. (Probably not.) But Tokuko leads with forgiveness, and in doing so, she then finds the freedom and wisdom necessary to stand up for herself in a powerful, yet non-combative way. Talk about grace!

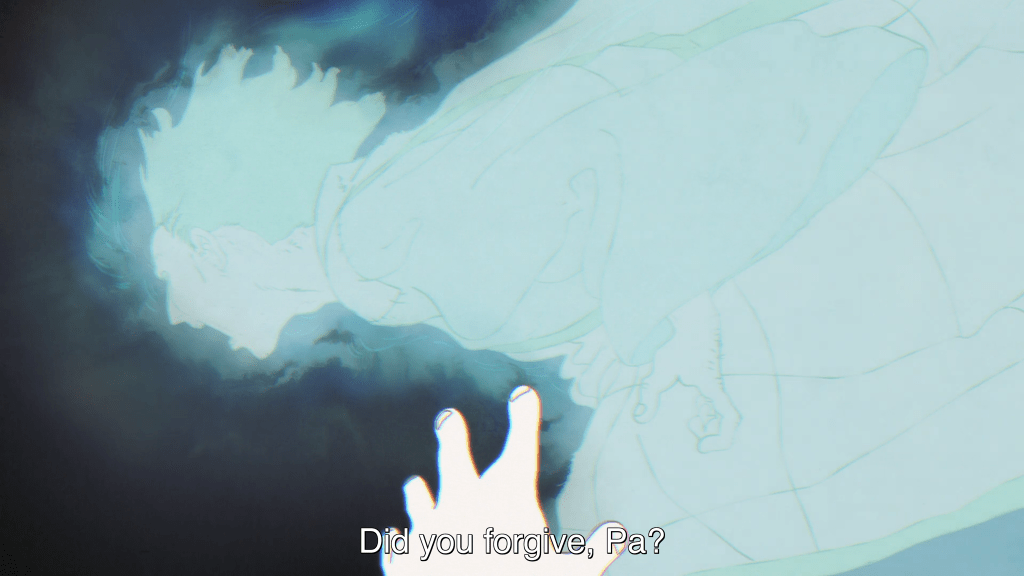

Tokuko’s forgiveness is equally transformative for Biwa, with whom she shares her vision for a different kind of world. The young girl is thrown into inner turmoil as she listens to Tokuko, her desperation for a world in which forgiveness is possible bubbling to the surface. When Tokuko speaks of forgiveness, Biwa sees the ghosts of her Pa and Shigemori, her adoptive father-figure, and asks them if they forgive. The implication is clear: Biwa wants to know whether they forgive her. After all, it had been her mouthy defiance that got her father executed, while she may well believe that she could have done more to save Shigemori, given her gift of supernatural foresight. In both cases, Biwa had remained an observer, frozen in inaction as they breathed their last.

Biwa wants to live in a world where she can be forgiven for this.

But Shigemori’s ghost turns the tables on her and asks whether she herself has forgiven.

But who is there for Biwa to forgive? The dialogue offers no clues, but the answer soon materializes as Biwa decides an episode or so later to take leave of the Heike in search of her mother, the once-famous shirabyoshi dancer from whom Biwa inherited her heterochromia; the woman who could, perhaps, have helped Biwa to navigate the frightening powers that came with that pale blue eye; and the one who abandoned her and her father, leaving Biwa without even a name to call her own.

Biwa sets out on a journey to find forgiveness—not for herself, but within herself. For the first time, the girl-minstrel is no longer wandering aimlessly; she is now full of purpose as she searches high and low for her mother. Village after village, mountain after mountain, doubling back at times—Biwa dedicates a considerable portion of her life to this pursuit. She is tenacious.

Spanning several episodes, Biwa’s journey reminds us that forgiving is not something we just happen upon incidentally. It doesn’t come naturally. Instead, it’s something that must be sought out, sometimes for months or even years before that sudden realization comes that we’ve finally found it, we’re living in it at last. (I’m talking here, of course, about forgiveness for the major hurts and wrongs that we’ve suffered in life and not the smaller day-to-day things for which forgiveness can become far more habitual and easy, by God’s grace.)

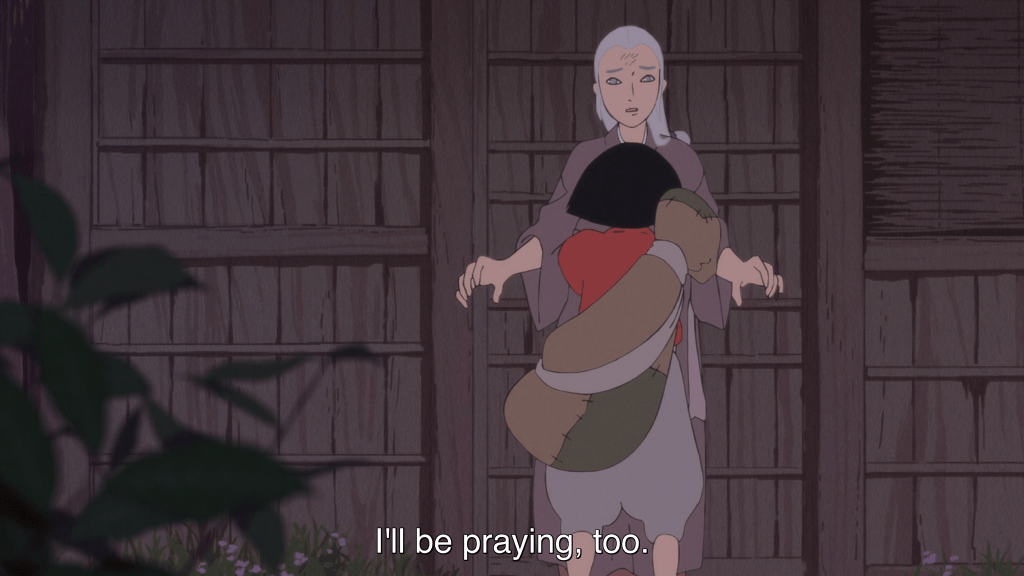

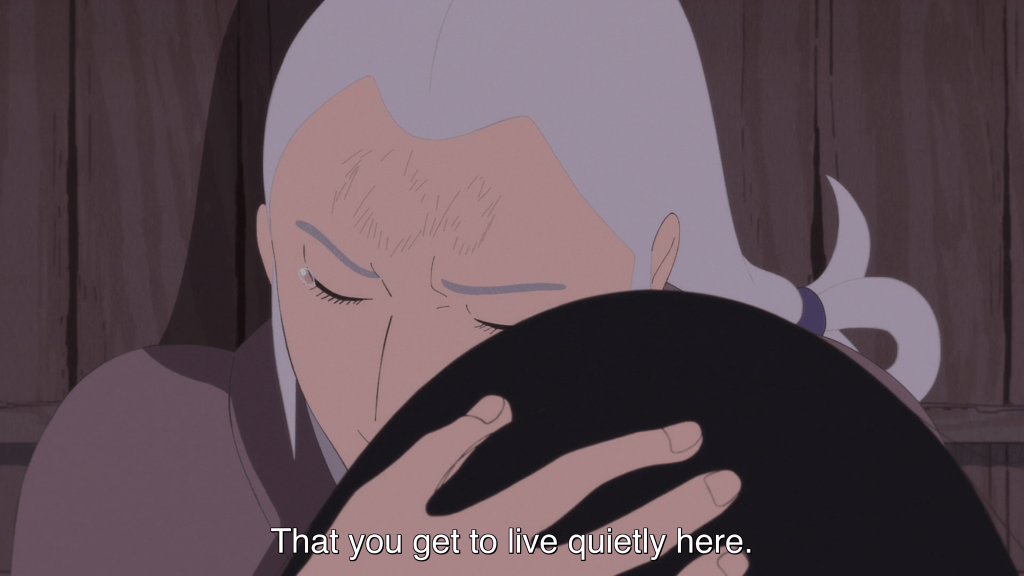

When she finds her mother, it’s not an easy reunion. Initially, Biwa feels rejected once again and pulls away to head back out into the world. But her mother’s humble apology reminds the girl of what it was she came there for, and she is able to turn back around and smile at the woman who abandoned her so long ago, and share with her the name she has chosen for herself. Biwa does this as if presenting her with a gift and not in a tone laced with years of resentment. In this instant, it is clear that although she does not say the words, Biwa has forgiven her mother. Later, when they do finally part, Biwa’s words and gestures overflow with a tenderness we’ve not yet seen from the girl. In forgiving her mother, Biwa regains the capacity for joy and affection that she lost as a child.

But the transformation doesn’t end there. Even more profound is the change in Biwa’s perspective on her role in life. She decides to return to the Heike so that she might witness the conclusion of their tragedy and weave it into a memorial song suffused with her prayers. It is the first step in walking out her newfound agency: All this time, Biwa thought herself incapable of doing anything about the disturbing visions of death granted by her mysterious blue eye, and as a result she held herself aloof from those she loved most among the Heike. Now, she realizes she is not so helpless after all, and although she cannot change their fate, she can at least change the way the Heike are remembered and the lessons that are learned from their story. She can, in fact, shape the world, at least in some small way.

This is the first step; the second is depicted so subtly that viewers would be pardoned for missing it, although it marks a dramatic reversal: Biwa reinterprets her visions of death in order to save a life.

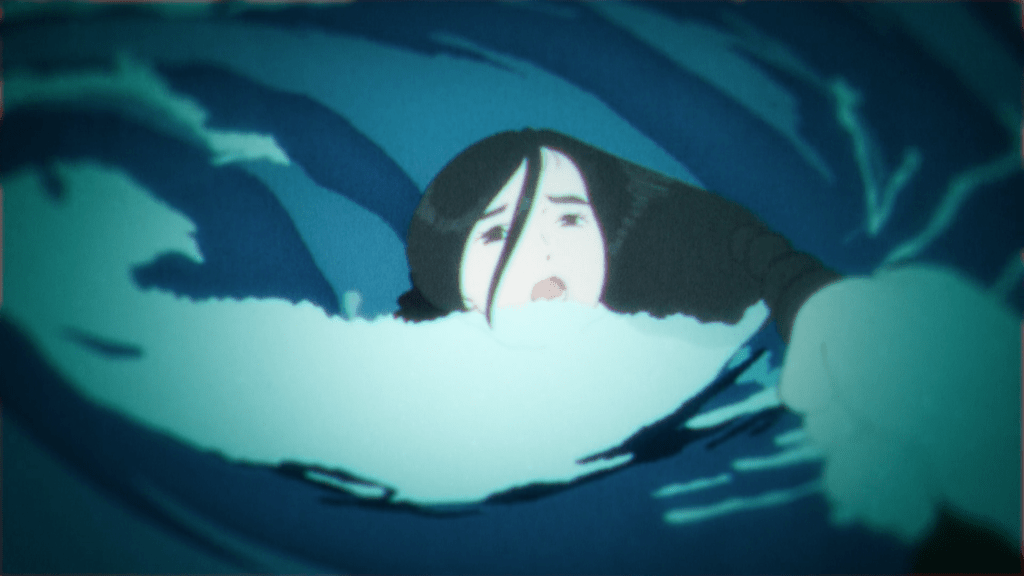

The most disturbing vision Biwa sees throughout the series, judging by the number of times she flashes back to it, is the drowning death of Tokuko. Initially hysterical in her attempt to prevent her friend from nearing the sea, Biwa quickly subsumed her urgency into a kind of numb fatalism. But as with Tokuko after forgiving her father, Biwa’s forgiveness of her mother quickens her capacity for agency, so that when Tokuko’s watery fate finally plays out before her, Biwa rejects it and refuses to comply. She reaches out to a distraught Tokuko, who is determined, in a moment of overwhelming tragedy, to embrace a watery grave, and speaks life over her, insisting that it is not her time to die, that instead she is destined to live.

Did Biwa see a new vision? Not at all. But she does see differently: Biwa reinterprets her vision of Tokuko amid the waves and whirlpools as a struggle for life rather than surrender to the throes of death, and chooses to partner with this perspective—one that is far more in keeping with the Tokuko she knows, a woman who is determined to bloom even in the mud. And so Biwa speaks out life to convince her friend to see it too. Biwa finds her own agency where before fate was the only actor she recognized.

Where fatalism tells us we are wounded and broken, forgiveness tells us we can release healing to a wounded and broken world. Where fatalism tells us that death will win in the end so why resist, forgiveness introduces us to our own agency to shape a new life in the meantime. In The Heike Story, fatalism told Tokuko she was a pawn, but her act of forgiveness showed her that she had an unquenchable power all her own. Fatalism kept Biwa isolated, her heart locked up in detachment, but forgiving her mother showed her that her love could make a difference; her love could even save a life.

What is most beautiful about the story of forgiveness in this series is the way it leads to a life of prayer for both Tokuko and Biwa, and then how those prayers, in turn, become The Heike Story itself, composed and sung by Biwa, its threads gathered together in harmony by Tokuko, the only surviving Heike to speak of what befell her clan.

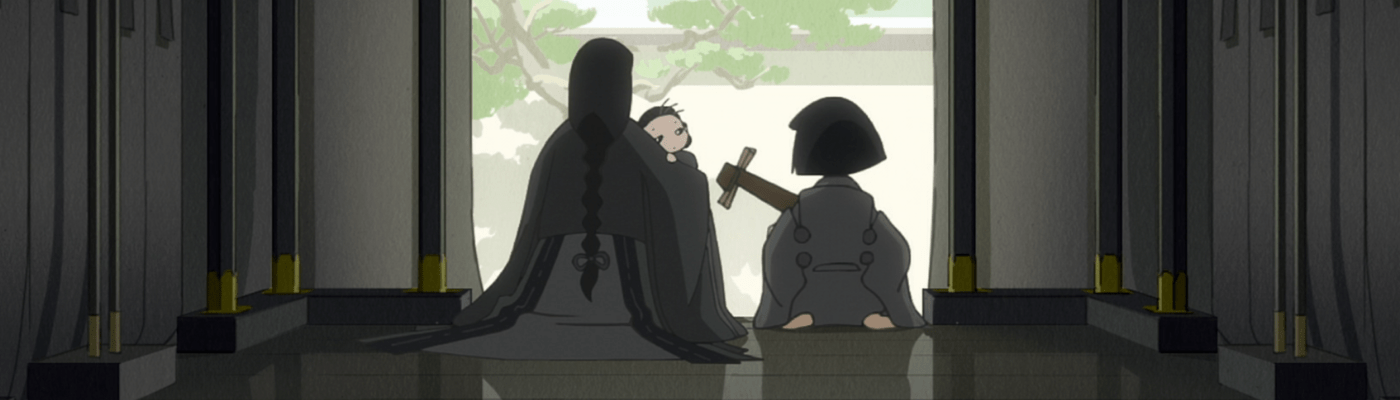

But what is most clever about this story is that it was all foreshadowed at the very beginning of the series in episode two, with the story of Gio, the shirabyoshi whom Biwa mistook for her mother. She is the first to choose forgiveness (toward both Kiyomori and a friend-turned-rival) and in so doing, discovers that she could remake her world and free it from the flavor of bitterness. And like the two who follow her in the way of forgiveness, she too devotes her life to prayer.

Although The Heike Story unfolds in the context of Buddhism and ancestral prayer, the connections it makes between forgiveness, agency, and prayer are critical for Christians, too.

Forgiveness is unnatural, but in choosing to pursue it, we rediscover our God-given agency in circumstances that would otherwise have us believe we are powerless in the face of other people’s sin. Because God does not abandon us or forsake us, even when others wrong us, and one of the ways he demonstrates his faithfulness is in enabling us to do something as radical and subversive as forgiving when it is undeserved.

We can’t forgive on our own though, which is why prayer is so crucial. Bitterness hijacks our prayer life—you know, that voice in our heads that is constantly narrating? It was designed to be in conversation with God himself and not just with ourselves or for the purposes of replaying or rehearsing conversations with others. Those conversations, that narration in our heads—that’s prayer. Or it can be; it should be, even. And sometimes, when forgiveness is so very hard, it’s partly because we’re praying to bitterness; we’re rehearsing unforgiveness in that monologue in our heads. At least, I know this to be the case for me.

Forgiveness starts, then, with prayer, with turning that monologue of woundedness into a dialogue with the Holy Spirit; that listing of wrongs suffered into a statement of our desire to let go of the hurt and our right to be offended and instead bless our enemy. Or at least, as a first step, stop cursing them. It can be a long road as we walk it out step by step, journeying village to village, mountain to mountain, sometimes doubling back until one day we find we’re finally there, on the threshold of a place called Forgiveness.

So let us take heart from Tokuko, who forgave in order to redefine the world and then found her place in it; and from Biwa, who forgave in order to live in a world where forgiveness was possible and then found that she was capable of so much more than she had ever dreamed. And let us remember too that unlike them, we are not alone in this journey; there is one who will partner with each of us, right there, waiting to hear from us and whispering the invitation to forgive.

Let’s change the world!

The Heike Story can be streamed on Funimation.

- Film Review: All You Need Is Kill - 01.15.2026

- First Impression: Kaya-chan isn’t Scary - 01.11.2026

- First Impression: Dead Account - 01.10.2026

Thank you for this superb piece of writing! I want to let you know that you’ve helped restore my faith in the value of close readings from alien cultural contexts.

On the one hand, it is true that the moral you draw from the tale is antithetical to its original intent. The Japanese verb “許す,” which Tokuko uses and is translated as “forgive,” doesn’t really have the Christian values you’ve assigned to it here—shame-based cultures simply don’t have quite the same concept of “forgiveness” as guilt-based ones. The original meaning is closer to “permit” or “allow”; Tokuko is saying that she chooses inaction by choosing not to hate those who have wronged her. In Buddhist philosophy, this choice not to participate in the chain of hate is salvific, because it removes one link from that chain and ultimately destroys it.

But in Christianity, as you demonstrate, “forgiveness” is a choice to do something—not to destroy the chain of hate by refusing to add another link to it as in Buddhism, but actively to take up the hammer of grace and smash that chain to pieces. Reading the original Heike Monogatari with that definition of forgiveness is probably impossible, but it works shockingly well for this adaptation, especially given Yamada’s significant inclusion of Tokuko’s refusal to join Go-Shirakawa’s court (a historical event that’s not depicted in the original tale). By grounding your close reading in careful attention to the narrative, astute analysis of the anime’s thematic priorities, and a considerate reframing into a new cultural and religious context, you’ve offered an encouraging fresh perspective without warping the narrative to match a predetermined theological conclusion. Thank you once more for being a model of Christian close reading done right!

PS: There’s another, equally encouraging article to be done on the nature of “prayer” in this anime, which again is pretty fundamentally different in Buddhist and Christian contexts—but speaking as a Christian living in Japan, Biwa and her mother’s “どうか。。。どうか。。。” moves me to tears. It’s a bit difficult for me to articulate, but that “please… please…” somehow captures the imago Dei I see in my Japanese friends, colleagues, and neighbors every day, which is all the clearer for being expressed in such a culturally divergent fashion.

This is incredible! Thank you Crowboy for sharing these really helpful insights into the language that Tokuko uses, and what it means in the Buddhist context! That makes so much sense. And also makes the plotting that Yamada and Yoshida develop even more meaningful: it’s after choosing forgiveness in the sense of inaction that Tokuko is actually empowered to take action. My copy of Heike Monogatari is arriving in the mail tomorrow (I’ve only read bits and pieces of it so far), but it seems to me that this adaptation is pretty radical in how it has woven together all its little details and gestures, and with the creation of Biwa as well.

You are absolutely right that there is room (nay, even a necessity!) to consider prayer in this series as well. (In fact, we’re always looking for guest post writers, so if you had anything in mind…[meaningful ellipsis] 😉 ) That moment with Biwa and her mother shredded my heart. This may seem like a tangent, but I wonder if you’ve read Makoto Fujimura’s Silence and Beauty? He really dives deep into this exact thing that you describe here, about seeing the imago Dei in Japanese people and culture. It’s such a powerful and moving book.

Thank you so much for taking the time to send such an encouraging and thoughtful comment! I really appreciate it, and am so glad that this post has helped restore your faith in the potential for Christian close reading! I so wanted to honor this series in all its richness and subtlety…

I’m glad to be helpful, and thank you very much for the recommendation—I’ve read Silence many times, but I know Makoto Fujimura only by name. I’ll definitely check out his work.

I’m thrilled to hear that you’re checking out the original! Honestly, the adaptation is shockingly faithful, both to the epic and to history, but of course there is so much material that can’t be covered in an 11-episode series. The main shortcoming of the anime is that the secondary theme of its source doesn’t quite come through. The primary theme, obviously, is transience; Biwa’s struggles with keeping memory and keeping faith in a world of impermanence perfectly reinforce this theme in the adaptation. The missing secondary theme is that other great Buddhist concern: suffering, specifically the compassionate idea that suffering is always a tragic and horrifying thing, even when it is happening to people who amply deserve it. The tale never allows us to rejoice in the poetic punishment of some “villain”; it is uncompromisingly even-handed in its descriptions of the agonies of pain, loss, separation, and failure, often going out of its way to remind us of the suffering the common people are feeling while we hear about the heroic deeds of noble warriors. The somewhat sanitized adaptation unfortunately loses this power to shock us, although whether that loss was a necessary step in the process of adaptation is up to you to decide.

Finally, assuming that you’re reading the Royall Tyler translation (which is really, really the one you should go for if you’re reading the Heike Monogatari in English), you may be somewhat confused to find that many characters are referred to by different names—for example, Tokuko is always “Kenreimon-in.” At the request of a friend who was having trouble keeping all of the people in the adaptation straight, I wrote up a complete character guide you can find at

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1htH-faA6vELGWVh74qxf3fLdLAypzzaljhQSWsOPyMM/edit?usp=sharing

which may be useful to a reader as well, since it includes some of the major Genji figures (like Yukiie and Kajiwara no Kagitoki) in the third chart. Enjoy the story!

Fantastic! Thank you for the link (I will certainly make use of it!) and the recommendation of which translation to read — I’ve ordered that one now, as I well know the difference a good translation can make! (Edit: Oh my goodness, just clicked the link, and this document you’ve put together is Masterful! Truly, a work of art. Thank you so much for sharing it!)

This representation of suffering, and the impossibility of villainizing any single character as a result, is really intriguing. Reminds me a little of Ranking of Kings which, although not foregrounding suffering per se, also refuses to let us judge any one character. Looking forward to reading the _Heike Monogatari_ with these two themes of impermanence and suffering in mind.

Given the vast amount of content left out of the series, wouldn’t it be interesting if Yamada/Science SARU were to develop a second season, in the style of Non Non Biyori where they retrace the narrative using different elements/stories?

What a wonderfully well-written comment to a wonderfully well-written article! I spent many years involved with Buddhism as I was questing for answers and you captured that viewpoint on forgiveness (via detachment) magnificently. And absolutely it’s a valid and wonderful way to go, I just happen to like smashing things so I prefer the Christian view on it, LOL. Loved that metaphor.

For me, I’ve started using the word “mercy” in place of forgiveness. “Forgiveness” carries some baggage for me. There is a subtle sense that forgiveness is somehow deserved (or earned) via mental gymnastics by which you see things from the offender’s point of view. And this is very useful and valid at times. But…

I really am able to let go when I think of mercy. Mercy says, what the person actually did WAS wrong and no amount of counter-evidence will change that fact. And I am well within my rights to take the easy route, try to punish them somehow, an eye-for-an-eye and all of that. The recently departed Bishop Tutu would literally say to pick up a rock, that represents your anger at how you’ve been wronged. You are fully within your rights to pick up that rock and metaphorically hurl it at the offender. But God is asking if you would voluntarily give up that right, to drop the rock.

Forgiveness for me is like a judge saying there is insufficient evidence to convict so they go free. Mercy says they are guilty but the punishment will be commuted. Why? Because God has opted not to slap me around for every mistake I’ve made. He’s been gracious with gentle corrections in my life. He’s let things go unpunished entirely. And He’s asked me to pay it forward. To let Him handle the life lessons that the person needs to overcome their “missing the mark.”

All of this is totally on me, I don’t know how I got the different connotations in my head. But if this sounds like you too, maybe try a different word that you won’t get stuck on.

(And it should go without saying this does not remove the need to protect those who are the victims of violence, prejudice, and any societal lawbreaking. I’m speaking here of all the personal grievances we have.)

Thank you for the kind words, and for your perspective! As you point out, in additional to the diverse societal framings of “forgiveness” I mentioned in my comment, each person has a different concept of the term. For me, forgiveness has a much more “Christian” feeling than mercy, an idea which I freely acknowledge makes no sense—I have that impression simply because I tend to think etymologically, and mercy, with its Latinate origin, feels like a dispassionate legal term to me, whereas forgiveness, coming from an Old English root literally meaning “complete giving,” feels much closer to the self-sacrificial action of grace that forms the heart of the Christian worldview.

As you also suggest, a theologian would say that forgiveness entails giving up the feelings of resentment, anger, and hatred that we hold towards those who have wronged us; mercy entails not giving evildoers their “just” reward. (I don’t think that forgiveness requires that we take the offender’s point of view or that we “dismiss” the offense; it simply demands that we see the offender as a fellow-human and fellow-sinner, rather than as a target of retribution.) By this definition, forgiveness feels to me like a much more human capacity, whereas mercy feels more rightly within the province of God. To show mercy to someone is to imply that we have the right to judge that person, and that idea makes me nervous: the Bible is absolutely packed with passages like James 4:12 (“There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the one who is able to save and destroy. But you—who are you to judge your neighbor?”) suggesting that God alone has the right to pass judgment on human souls. To exercise forgiveness in the manner of Biwa and Tokuko, however, is to help two people at once: the other, by proffering the opportunity to escape the chain of retribution, and the self, by turning aside from the resentful compulsion towards retribution that leads us away from the Divine. Of course, the forgiveness we offer may not be accepted (Haibane Renmei has the most incredible depiction of the difficulties encountered in accepting forgiveness), but forgiveness still makes a positive change in us and thus in the world, while mercy (to my thinking) has less a transformative and more a merely legal power.

But of course this is merely my own thinking, which is probably based more on gut feeling than actual logic! I really appreciate seeing your concept of the terms, too.

I agree with Claire, you truly have a gift for words and I would love to read more if you ever felt the desire to write a post here!

You know what’s funny is that I have held the exact same view on mercy as you do. And for some reason I found it more malleable to change its connotation rather than forgiveness. Definitely a personal quirk! And ultimately the truth is we are incapable of making good judgments about others, planks in our eyes and all that. Jesus spends a lot of time on this theme, doesn’t he? When you can really accept this fact it does make the forgiveness process easier.

Thanks for the recommendations for reading as well! As soon as I have time I would love to read the source and rewatch this one.

I want to say that reading what you and Claire have shared so eloquently really is on target for the mission of this site. You are showing those who hold the common prejudice that Christians are somehow dim-witted and incapable of rigorous analysis (else why would we believe in such outlandish things?) that nothing can be further from the truth. Yes, faith and wisdom do require stepping beyond the calculating mind but that is a deliberate choice (and Buddhists would agree).

Likewise, you are showing the depths that can be plumbed from anime, which many Christians would consider frivolous at best. You are exactly the kind of ambassadors that are needed to start changing these misconceptions!

This has been such a rich thread! I’ve learned so much from you both, Crowboy and Sojiro, and am convinced of the need to do some pondering on mercy and forgiveness and how they compare to and complement one another.

Thanks so much, Sojiro, for the encouragement re: hitting the target for the mission of the site! It really means a lot!

[…] meaning and deeper tenderness on each viewing, as her work practically vibrates with humanity. The Heike Story in particular surpassed even my considerably high expectations and has found a permanent home in my […]

[…] and original work of art in his exam the next day. Meanwhile, in overturning Tokuko’s “fate”, Biwa discovers her own agency and gains a perfect ending for her song of the Heike, ensuring that the final word of their […]

[…] The Heike Story: A Tale of Forgiveness? […]