Edward Elric, the Fullmetal Alchemist, has the inscription “Don’t forget 3.Oct.11” carved inside his silver pocket watch, the symbol of his office. It is a memorial of the day a new life opened up before the maimed Elric brothers—one of alchemy, detective work and military service. And if we had silver pocket watches at BtT, mine might say: “Don’t forget FMA:B”.

Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood was my doorway into anime, and I have walked side by side with the Elric brothers again and again ever since. I’ll do it once more in this article, exploring how they inspired (and still inspire) me, encouraging my love of God. Kind of odd, since Edward loudly proclaims his atheism and his devotion to alchemy, while I’m a convinced Catholic. Or is it?

FMA:B is arguably the anime of my generation. It was also the very first series I ever watched back at college when we decided that a nightly anime episode during exams was the perfect study break. I was a Ghibli fan (and had been a Pokemon kid), but nothing more. I was soon won over by FMA:B though. Episode after episode, I experienced an increasing sense of sense of awe. What a well-crafted, sincere, thoughtful fantasy adventure! And much of that awe had to do with… alchemy.

What is alchemy? Potter-esque magic? Modern science? Raw power? And, whatever the answer, why do both versions of the show contrast it with Christianity? This happens explicitly in the 2003-2004 Fullmetal Alchemist, which I completed last year, and implicitly in the 2009-2012 FMA:B, which I have rewatched three or four times. Why did this story speak to me so deeply?

Like the Elrics, I needed “the truth behind the truth.” Watching Erased after FMA:B further convinced me that there was something about anime and Christianity, something about the truthful way it can portray the depths of the human heart, made by God and for God. I found friends and guides as I chased the parallels I saw, landing at BtT and the brilliant analysis by Annalyn. A new world had opened up.

Those who were writers then might remember my never-ending comments about the shows I discovered and their parallels with the Gospel. But, again like the young alchemists, I also discovered some potentially troubling things lurking in the depths of my new fandom. Annalyn had a word of caution to offer regarding Brotherhood.

Others here had explored connections between this franchise and their faith, commenting on mercy, the unity of Mankind, and disability as a Christian, with the hope of full restoration in Heaven. But Annalyn warned that some anime contain life philosophies that contradict the Biblical worldview, principles that Christians might take in uncritically.

An idea is a very powerful thing. And when it is embedded in the beauty of a story, we can absorb it through our emotions rather than our conscious thought. Annalyn flags up the fact that, apart from TV-MA content, other things might need further thought, noting that FMA is “very humanist; that is, it emphasizes humans’ ability to improve, save, and occasionally sabotage themselves, ungoverned by an omniscient and omnipotent God.”

Annalyn acknowledges the presence of themes of love and forgiveness, but she also points out that the story is human-centered and human-powered, and that “all superhuman or deity-like characters are either defeated by the protagonists’ crew or learn a lesson from them and come to their side.” It’s a great article on a thorny topic, that of Christians, anime and ”the line”.

“The eye is the lamp of the body. So, if your eye is healthy, your whole body will be full of light” (Matthew 6:22). Keeping my faith alive is a priority for me, and I took the problem raised by Annalyn seriously. I feel differently about the story of the Elrics though. I commented on this then, but I feel that now, after eight years, I’m ready to explore the question more fully. Is the FMA franchise hostile to a Biblical worldview? Is the story humanist?

Let’s begin with that. What is “humanism”? A contemporary definition would be “a democratic and ethical life stance, which affirms that human beings have the right and responsibility to give meaning and shape to their own lives. It stands for the building of a more humane society through an ethic based on human and other natural values in the spirit of reason and free inquiry through human capabilities. It is not theistic, and it does not accept supernatural views of reality.”

Humanists come in all flavors, though. A common version nowadays is “scientist humanism,” which sees the advance of science and the scientific worldview as the backbone of an ethical life, both personally and socially. Edward Elric, whose arm and leg have been replaced by “automail”, is pretty much this. Both versions of FMA open with the criticism (or caricature) of religion that this humanism usually engages in. You know, the fat, power-hungry priest. Meet Cornello!

Cornello is a fake miracle-maker priest of “Leto”, a Sun god in a church surrounded by Catholic-looking statues. He promises miracles, resurrection, and the forgiveness of sins to ignorant masses. Edward, our hero, believes not in gods or miracles, but in alchemy, a power that allows him to transform things, instantly rearranging their components through “equivalent exchange”. This knowledge helps young Edward expose and defeat old Cornello.

Here, alchemy stands in for modern science. Vulnerable people who have been hurt might want to believe in miracles, but according to Edward, they should just face the facts and continue loving their humanity, finding support in a solid scientific understanding of the world. “You are alive!” Edward tells the grieving Rose, who hoped for her boyfriend to be resurrected. Pretty straightforward, right?

But here come the twists. First, as alchemists, the brothers are agents of an industrial, militaristic regime somewhere between Meiji-era Japan and Germany during the First World War. As in our world, science is not only knowledge, but power. And it comes with its military-industrial complex. To use this power, you need to contribute to it and accept the… grisly side effects. And that’s not all the alchemical regime has in store for the “freed” citizens of Lior.

We also learn that, as good humanists, the Elric brothers dismissed the old taboos of alchemy and tried to resurrect their mother by transmuting the matter of her body. Oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium, and phosphorus. Potassium, sulfur, sodium, chlorine, and magnesium. All the right percentages. And finally, genetic information from her remains. Is there anything more to a person?

Humanism scoffs at the notion of the soul, the spiritual part of a person. And yet, the siblings find out that the being that rises is not the mother they loved. Instead of the scientifically predictable outcome, their act opens the doors of a world of immaculate emptiness and alchemical symbols, and a being that calls himself “the Universe, God, you” addresses the protagonist, opening a gate to show him “the truth”.

The price is Edward’s limbs and Alphonse’s entire body. But even after learning the hard way that he doesn’t live in a humanist world, Edward stubbornly remains a humanist. He curses the taboos and mysticism that he cannot deny. He dreams of a world of human progress and alchemy. But his dream proves to be a tricky one. Humanity’s main problems are not external. They are in us. They are us.

Both in our world and in the show, the humanist narrative might be hiding more sinister parts of the story. In the past, people were superstitious and obscurantist, we are told. Science makes them more aware, and thus enlightened and rational, and in turn, better. Or does it? In Fullmetal, the supernatural certainly exists, but (spoilers ahead) the antagonists are not supernatural. Instead, the darkness comes from the most “enlightened” of all alchemists and their work.

The “Homunculi” are our creations, our ambitions and selfish projects in the flesh. They are the embodiment of our sins: Lust, Pride, Envy, Wrath. And those behind the homunculi are the very alchemists who advance science. In the end, the villains of FMA embody the two pre-modern cautionary tales about science: Faustian alchemists and Frankenstein’s monsters.

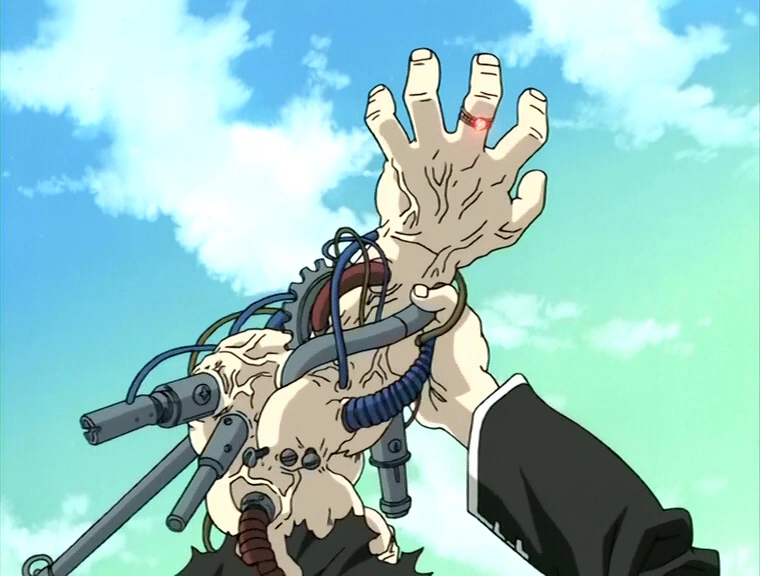

The “Faustian” are those who, like Faust in the old German tale, trade the meaningful things in their life for power, making a metaphorical “deal with the devil”. The monsters, in turn, are those who are desperately incomplete as a result of these dark trade-offs, living a grotesque, falsified half-life that was supposed to be better than human. FMA expresses these concepts through pretty effective body horror.

Alchemy is a cool, unique kind of magic for an adventure story, and the perfect stand-in for the science of scientism. Historical alchemy was a predecessor of the science-based humanist project that triumphed in the era of the revolutions and defined Western culture, with many Enlightenment figures dealing in both. But it was also “magic”, the attempt to manipulate reality itself.

Some of this alchemy worked and was built upon in our scientific tradition. Most of it—including the central search for a method of transmuting elements and creating life—didn’t. But what if it had? By exploring this idea, FMA gives us a vivid representation of “existential technology”, the attempt to create and manipulate the meaning of our lives through techniques, rituals, and formulas we control. What if life, happiness, love, truths, needs or facts could be created, altered, or suppressed at will, by rearranging their basic components?

Can such technology exist? For some, it just has to. If human beings truly have the right and responsibility to give meaning and shape to their own lives, they need the means to do so. Humanists tend to believe that the right combination of engineering, psychology, politics and medicine can do this for us. But, even if all these are good, useful tools, we cannot use them to manipulate the most meaningful aspects of our lives without changing ourselves in the process.

Might it be that trying to make ourselves (individually or collectively) the god of our own realities results in us damaging our nature, and sacrificing the meaning that was already there? Is it possible that meaning is only ever found and embraced or rejected? That existential technology is itself a Faustian deal?

It is probably no accident that the Germany of the 1920s, the main inspiration of this “Dieselpunk” world, was the worst hit by the disillusionment inflicted by the Great War in the West. Just as the flame powers of Mustang might lead to the Ishval War, the scientific revolution led to mustard gas, the arms race, the trenches, and aerial bombings. Another clear inspiration is the building of Meiji Japan, with its horrific dark side.

Those were the days of the so-called “Lost Generation”, the ones who realized that they weren’t progressing on a linear trajectory toward utopia. Losing limbs, family, friends, and countries, some turned toward psychics and mediums, while others tried to regain their hope in humanism. And the worst was yet to come. Nazi Germany and the horrors of the atomic era were just around the corner.

Just as the Elric brothers’ attempt to rebuild Trisha Elric from her pieces resulted in something monstrous and came at a high price, so too does the attempt to control and manipulate meaning through “existential technology” affect both the user and the creation, deforming them. The dreams of human reason, unchecked by wisdom, produce monsters. The “shape of our lives” is beyond our control. Edward and Alphonse were not fit to be gods, nor are we.

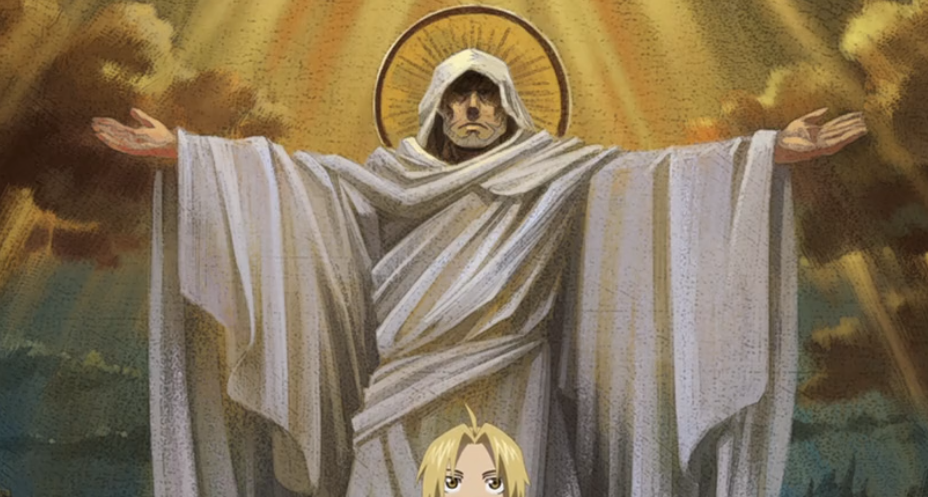

What is it about the religious callbacks in FMA, though? “Father” disguises himself as a tunic-wearing God. Dante takes the name of the great poet of Heaven and Hell. Well, humanists may think they have expelled religion from their world, but like a repressed memory, it emerges again, as the new alchemical regime takes twisted religious forms behind the veil. Why? Because the existential thirst is still there, calling out to be slaked.

This duality brings us to the “wilderness of mirrors.“ The Elrics’ journey is one of seeing themselves and their friends in their monstrous enemies, and vice versa. Ambiguous characters, doubles, parallels and lookalikes appear everywhere as the plot comes full circle. The religious concepts that humanism had rejected earlier in the story reappear at its core, though FMA and FMA:B interpret this fact in different ways.

Parents exchanging their children for the power to create life. Alchemists driven to genocide for the sake of public peace. Using an ungodly power to deliver divine justice. In truth, you can pinpoint examples of this wilderness in both versions of the story. But it is not the story of the Elrics, because the Elrics have something more: their brotherhood.

The Elrics’ mutual love is a personal, scientific, and political stance that embraces not just the two of them, but also their country, the people they come across, even the whole Universe. Their alchemy is one of wonder, and wonder helps us feel the balance, wisdom, and interconnectedness imprinted in the Cosmos; it helps us learn from it and use it for good, a lesson the Elrics learn while surviving on a desert island as children.

I think that this duality in the show complements a Biblical worldview. In the Book of Genesis, all things in the Universe are created in twos or threes: light and darkness, day and night, sea and land, Sun, moon and stars, birds and fish, man and woman. They are connected and complementary, a “family” under God, the Father. And God created humanity as an elder brother, to guard and rule Nature, to co-create with Him. To learn, to name, and to do.

The man of science can be also a man of faith: a disciple of the wisdom of God, a discoverer of His wonders. The Elrics are learning, too, investigating, experimenting, and changing the lives of those around them, and discovering undeserved mercy, love unto self-sacrifice, and the miracles of life. Edward’s atheistic stance at the beginning is balanced by the humbling moment when the brothers pray to God as a baby is being born.

The temptation to turn the deepest longings of our hearts into fuel and pieces of “existential technology”, to build monstrous idols with our hands, is also central in the Bible. Even if we don’t use the term “gods” or “idols”, we might live by and for our most beautiful works of art (statues or stories), our best political creations (enlightened values! Social movements! Democracy!) or the discoveries that give us power. We can try to use them to edit our own lives and excuse our faults.

The stories of Babel, the Israelites’ enslavement under the Pharaoh, and the invasion of Jerusalem by Babylon, are stories of pride, monstrosity, and moral collapse. The attempt to achieve a godly status makes humans inhuman. Deciding to reinvent life, family, humanity, the truth, morality, religion or human society makes us into instruments of our own ideologies, leading to monstrous failed experiments and persistent protests that nigh-divine power is just within reach.

Magic and idolatry are mere games of mirrors: no technology can change the meaning imprinted in us. FMA introduces us to the sympathetic Ishvalans, a monotheistic culture that rejects alchemy as an aberration. But withdrawing from the “modern” alchemical world in order to avoid evil is revealed to be a contradictory enterprise. Meanwhile, the series also highlights the dehumanizing role played by scientist humanism. So… okay, we’re alive, and we should walk. But where to?

This paradox turns the 2003 version of FMA into the tragedy of the disappointed lover, a common result of sincere humanism. The town you saved might go to the wolves as a side effect. Your medicine might be poisonous in some other way. Your core beliefs might be half-truths. Technology and politics, democratic or not, are power, and thus vulnerable to monstrous power logic. But, as an ever-disappointed lover, you keep trying. What else is left?

The thirst for meaning burns just as always, but the results are more and more ambiguous. What to do? For the humanists who truly love Humanity, there is no way out. Alphonse’s bittersweet meditation sums it up: he explains equivalent exchange, the foundation of alchemy, and adds that “at that time, we believed that to be the true way of the world.” Not anymore.

FMA turns this disappointment into a fantasy that stings, rejected by many, venerated by some. In the final episodes, Christianity gets an explicit tip of the hat and a clearly humanist one.

As we descend to an ancient German city, we learn that Christianity was the belief system of the “old world” that led to intolerance and total obliteration. The irony is that the substitutes, the alchemy-based Amestrians and the anti-alchemy Ishvalis, are both on the same path. For this version of the show, the human heart cannot cut itself free from Christianity (read: irrationality), and the wilderness of mirrors reigns, with a few elements of bittersweet hope.

But Christianity is more than a human belief system, and the humanist non-hope is not all there is. I won’t enter the debate about which is the “better” version, but the version that inspired me, and which remains in my top twelve to this day, is Brotherhood. Like many who fought and suffered during World War I, I believe in something more. And, even if every new age creates its own Fausts and monsters, I always will.

So, what is there beyond existential technology and its discontents? Well, here’s where brotherhood comes to the rescue. The brotherhood of humanity and Nature, of human and human, of human and angel, of human and God in Christ. A “true way of the world” that even a child can grasp, that never changes, that goes beyond equivalent exchange: life-giving love.

But it is late already, so I’ll leave the exploration for next time. Stay tuned for Part II!

Fullmetal Alchemist (2003) can be acquired on Amazon.

- First Impression: Love Through a Prism - 01.17.2026

- First Impression: Oedo Fire Slayer -The Legend of Phoenix- - 01.12.2026

- First Impression: In the Clear Moonlit Dusk - 01.11.2026

[…] Last month, I explained how FMA’s alchemy is a perfect stand-in for the scientific revolution, highlighting the contradictions at its very foundations and how its deconstruction creates a point of contact between the franchise and Christianity. This paradox is the tragedy at the heart of FMA (2003), but I contend that it becomes a sign of hope in 2012’s FMA:B. What is the difference between the two versions, you ask? Wait for it: brotherhood! […]