I’ve remarked before about my bitterness toward my last church. I’m still holding onto resentment, but healing is in sight—after all, I know both that the people there meant well and that it would be foolhardy to judge them when my own sins are mountainous. But seeing how difficult it’s been to work through even this pain, it’s no surprise that when church members and leadership are more fully and obviously engaged in sin than was the case in my experience, that their practices will not only hurt others, but could end their faith entirely, while also erecting a roadblock for future generations.

These effects are well portrayed through the fourth volume of Spice & Wolf (a review forthcoming in Reader’s Corner), in which the church once again plays a prominent role in the story. As the non-believer Lawrence and the wolf goddess Holo come upon a small village in their journey to find the latter’s ancient home, they discover that the local church and its clergywoman, Elsa, are at best ignored by the pagan populace and at worst, actively persecuted.

Elsa herself is not particularly inviting either, displaying a haughty and suspicious attitude. Yet over and over again, as Lawrence interacts with her, he notes that Elsa is sticking to her faith, which in these examples has everything to do with following the letter of the law, though not the spirit, such as when she utters deceitful words to hide something rather than speaking a plain lie.

Elsa obviously believes that she’s doing nothing wrong in these incidents, staying pure and perfect according to her faith. But if the religion of Spice & Wolf is roughly analogous to Catholicism, she’s missing the very heart of Christianity, of a central figure who explains that it’s what is in our hearts that counts, and who decries an establishment that only outwardly follows the law while rotting within:

Blind Pharisee! First clean the inside of the cup and dish, and then the outside also will be clean. Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of the bones of the dead and everything unclean. In the same way, on the outside you appear to people as righteous but on the inside you are full of hypocrisy and wickedness.

Matthew 23:36-38 (NIV)

It’s hard to blame Elsa, though. She is the adoptive daughter of the now-deceased Father Franz who, while himself seems to have been a very good man (we don’t know if he followed only letter as opposed to spirit as well), also became bitter over the years through his dealings with the larger church, and in particular the nearby diocese at Enberch, which exerts control over their town of Tereo. Volume four mostly deals with the larger village’s attempt to cancel a contract between the communities that favored Tereo, and which Franz had brokered before his death.

I get the sense that Father Franz was once full of optimism and hope. He arranged a great deal for Tereo, signifying how much he loved a village that didn’t in turn appreciate his faith. And yet, by the end of his life, there are signs that he’d perhaps become pagan himself. He certainly doesn’t seem to have passed on loving teachings to his daughter, who lives by her own righteousness rather than by the love of God and love for others. She seems to conduct her role out of duty to carry on her beloved father’s work.

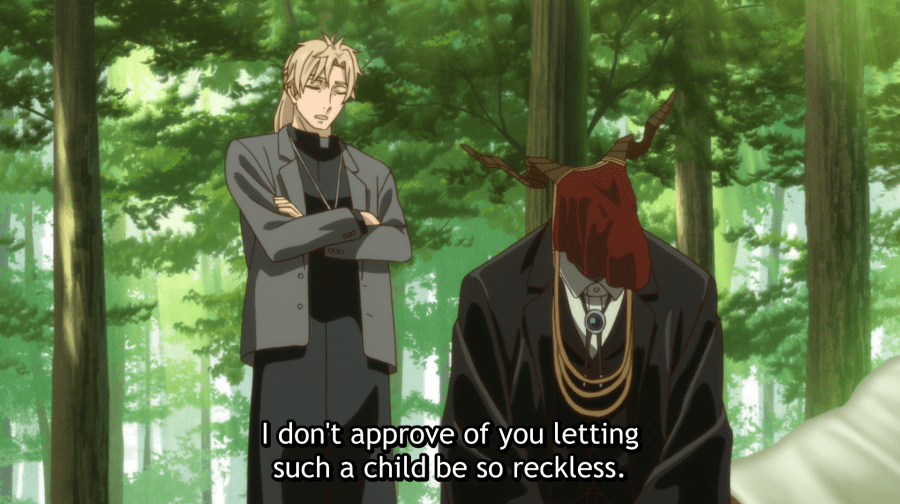

In The Ancient Magus Bride, another series set in the West (though in modern England as opposed to a late-Medieval, early-modern European AU), the effect of the church is seen not only one generation later, as with Franz to Elsa, but generations on down the line. Simon Cullum, the representative of “the church,” is tasked with keeping a close eye on Elias, who doesn’t trust him and refuses to be controlled by an institution. Elias is indeed antagonistic towards Simon, who by all accounts, seems like a kind man.

Titania, Queen of the Faeries, treats Simon with even more hostility. In fact, it seems that she would like to kill him, but when the two meet, she instead keeps her composure and thrusts him away to somewhere in the woods where he’ll wander lost for several hours. The typically kind Titania harbors nothing but hatred toward the church and its representatives.

It’s easier to gather where Titania’s anger comes from, and where Elias’ might as well, but is that because the church of this world has done wrong? Perhaps not, if one believes that the Christian God is the King of Kings and the only true god, even in this fictional world of pagan deities. However, there seems to at least be some issue with mediation, actions that the church could have taken to improve relationships and open doors for its ultimate goal of leading the flock to Christ.

Most immediately affected by this lack of direction is Chise, who demonstrates some affinity toward Simon, who in turn offers his assistance to her when they initially meet and shows concern later as well. Could Simon help Chise who, though physically saved by Elias and tended to occasionally by others, is still struggling so mightily inside? Simon can’t really even begin to do so because of the enmity between the church and magicians and their ilk.

Every life matters to God. Christ came to save the sinner—each one of us—and to offer life in abundance. Many will reject his call for one reason or another, but how terrible it is when one builds a wall in his or her heart because of the very institution Christ came to save us into, as I’ve found is often the case, when sharing stories of the church with many dozens of non-believers.

And if Chise represents one solitary life, treasured and significant, the church of Tereo shines light on what can happen should God’s people make profoundly sinful choices over and over again. The church of Enberch hampered or perhaps destroyed Franz’s faith (he seems to have preferred to embrace stories of the “olde gods”), which then affected his daughter’s view of religion and her ministry to an entire village of non-believers, who would rather worship their own deity. The contortion of Franz’s faith and that of his daughter then erected a wall between the people of God and those they would hope to reach.

And then, as volume four ends, a further nail is hammered into the coffin of faith as Elsa comes to a conclusion—perhaps honestly or by deceit (again, the “letter” of the law)—that some sort of synergy between faiths would be okay, mixing up the religion of the church and the pagan deity worship, which is symbolized, most tellingly, by a snake.

In just one generation, an entire village has moved from idol worship to a further sin of Old Testament “judgement and destruction” proportions, led by this village’s version of a Moses who has them look toward a snake, except that instead of healing, this would continue to lead them toward their eternal punishment.

Today, churches continue to deal with corruption, abuse, and many other active and terrible sins. Those with such profound issues point each precious soul in their vicinity away from God and toward the things of the serpent, the things of this world.

More common, however, are perhaps the “small” sins, the things we do or say because we do not consider our actions with enough thought beforehand or because we indulge in selfishness. These are the poor decisions we make and the hurts we cause others, particularly in the capacity of spiritual leaders on any level, from pastor on down to Sunday school teacher. Are we doing the gospel work that tears down walls, or are we building those walls up through selfishness, lack of character, and negligence? Are we speaking the truth while living it also, or are we only talking the talk, as Elsa does?

An individual believer’s ability to change pervasive problems in the church, as with the Enberch diocese in Spice & Wolf, may be limited. But the Christian’s sphere of influence is still significant. We can do the work that Franz failed to do, and guided by the Holy Spirit, we can have an impact on those closest to us. As we do the work of God, it’s no stretch to imagine that He will spread his love further and on down through the generations, too. But to participate in this commission, we must be introspective—examining ourselves for sin, humbling ourselves before God, and becoming obedient in our love for him.

But when we do this, love will overflow. To paraphrase, we will become the “[spice] of the earth,” spice to a dying world. And we will become that which reflects God’s light, instead of just another lamp under a bowl doing nothing for his kingdom, or worse yet—by obvious or subtle means—turning people away from God and toward the serpent instead.

We can be the spice, the salt, the light—or we can leave people around us worse off than we found them. It’s our choice, and there is no in between.

These seems contradictory.

You cant be both “spice of earth” while denouncing matter of this world as “serpents”. Is this world relevant or not ? If it irrelevant, then Church enriching its member and exploit others is also irrelevant. If it matters, then embracing “serpents” is not mistake.

These matters more regarding Salvation. Japanese Anime and American semi-secular belief regards that there are many way to Salvation (many believe Jews, Hindus, and their dogs can also go to heaven). These make (medieval) Church as hostile institution.

On the other hand if Jeses Christ as only avenue of Salvation, calculation is different.

[…] this volume—caused me to consider how those in power in the church may abuse their authority, affecting generations of believers and even young leaders. As usual, Spice and Wolf provides both getaway entertainment (sometimes […]

[…] few weeks ago, Twwk wrote a piece reflecting on the Christian church, its failures, and their cascading effects in the lives of both […]