This guest post was submitted by Bob Aarhus. In addition to his short bio at the end of the piece, I’ll add that Bob has been a long supporter of Beneath the Tangles and a model for this particular blogger in how to be a thinking, compassionate Christian. I’m proud to present this excellent article. If you would like to submit a guest article, we welcome pitches through our guest post submission page.

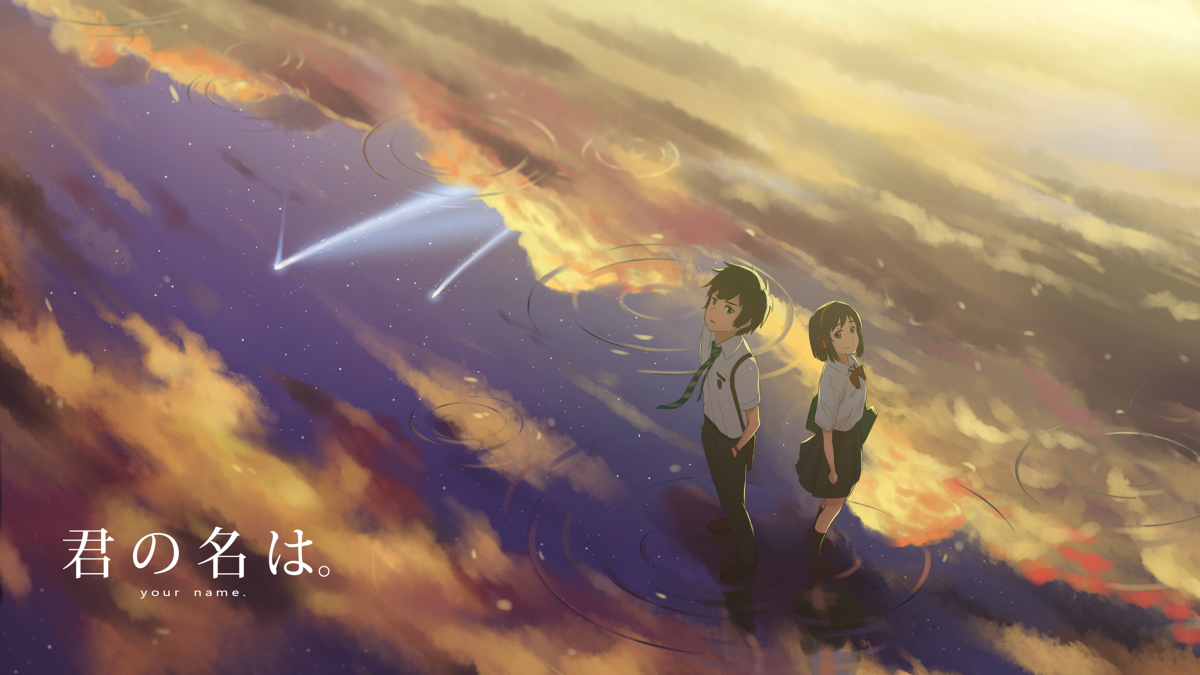

Makoto Shinkai is a magician. Well, not quite. He’s an anime director with a reputation for telling stories that focus on relationships – often relationships that end in disappointing ways. But in his latest effort, Kimi No Na Wa (Your Name), he shows us that he, too, can use misdirection to put us under his spell. And, like all things magical, there may be more depth to this film than meets the eye.

If you have read the reviews, or anything about the box office performance of Kimi No Na Wa, you know that it has been well-received. It earned scores of 98% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes, rocketed to the number one positions on My Anime List and Anime News Network user surveys, and is now the highest-grossing anime film worldwide in history, surpassing even Miyazaki’s Spirited Away masterpiece. As the accolades continue to roll in, you have to ask the question: how did this teenage love story with a silly premise draw in critics and crowds so effectively?

The answer lies partially in Shinkai’s sleight-of-hand. We are led to believe (from the trailers and early press releases) that the story is about the body-swapping of two Japanese teenagers, a boy who lives in the heart of Tokyo, and a girl residing in rural Japan. But that’s just the hook to get us interested. Truth be told, the body-swapping occupies just less than a third of the total screen time. It’s a clever ruse that allows for gender-oriented jokes and a “walk a mile in my shoes” sort of premise. But that’s not the point of the film.

The real theme of Kimi No Na Wa is introduced to us subtly but effectively in one of the movie’s least frenetic and most contemplative scenes: the trip to go-shintai [the ‘body’ of the temple god, meaning the location of worship], where we learn of musubi. Musubi in the Shinto context means creation, harmonization, and combination. In obaa-chan’s monologue, musubi also signifies the flow of time, filaments in the braided cords, the incorporation of food or drink into the body. Not only does musubi apply to physical or temporal objects, it also applies to relationships. The threads of our human existence with others combine, twist, and sometimes break, only to be reunited at a future point.

Shinkai’s work presents us with numerous dichotomies: the urban and the countryside, the heavens and the earth, togetherness and separation, life and death. While seemingly opposites, he says, they in fact join at critical points, just like the strands in Mitsuha’s ribbon. We walk through portals of choices – notice the film’s obsession with sliding doors – and we weave tapestries of narrative between the extremes. It is Shinkai’s masterful manipulation of these elements that evokes the most substantial emotions of the audience at key points in the film.

But that can’t be the only reason for the movie’s success; emotional manipulation is the hallmark of both the romantic and the propogandist, and many previous efforts have failed. I suspect Shinkai has imbued his creation, consciously or otherwise, with words of Real Magic; like LeGuin’s “true name” in Earthsea or C.S. Lewis’ Tao in The Abolition of Man, the writer and director has rested his work on several facets of Reality “beyond predicates” (again, Lewis). The audience understands these fundamental pillars of existential truth without the need for further proof or exposition.

Chief among these truths are the core philosophies of our two leads, Taki and Mitsuha. Taki, faced with the separation from the one whom he loves, says “I wanted to tell you: wherever you are in the world, I’ll search for you.” Meanwhile, Mitsuha states as her profession of faith, “One thing is certain, if we see each other, we’ll know.”

Despite our existence in a world where fidelity is fickle and knowledge of others often obscured, we all long for these truths. We want to have relationships where we are eagerly desired and sought after. We are the lost sheep, we are the prodigal son, we are the maiden anxiously awaiting her beloved, and we want someone to be there for us, someday. And, we believe that, when that time comes, we will recognize it.

It is the very frustration of these principles that propel the plot and have us rooting for our newest victims of outrageous fortune.

Because, you see, for such an arrangement, someone has to pay the price. In Kimi No Na Wa, to depart kakuriyo, the underworld of the go-shintai, you must leave behind what is most important to you. Taki, in the body of Mitsuha, unknowingly sacrifices his connection with Mitsuha and the random switching related to it; when obaa-chan awakens him (“Ah, Mitsuha, you’re dreaming right now, aren’t you?”), he bolts upright in bed, and the tears begin to flow. “Tears. Why?” he asks, but we already know the answer: his soul recognizes the break, and he weeps for the loss, though his mind has not yet caught up. This (along with the need for the universe to resolve some paradoxes, but that’s another post) will eventually lead to the forgetfulness that will complicate Taki’s efforts: he will come to know he has a longing for which he will search obsessively, but he does not know the object of it.

At the “same moment” in the narrative, Mitsuha’s soul senses the loss, and she cries as well, but does not understand. It disturbs her enough that she suddenly skips school and runs off to Tokyo to try and find Taki. It is on this impulsive trip that Mitsuha will have her crisis of faith. In a city of 30 million people, she indeed encounters Taki – but unbeknownst to her, it is the Taki of the past that has yet to swap bodies with her, and he does not recognize her. How could this be?, you can almost hear her cry. He’s Taki, we’re supposed to know each other... She returns home and, in the perfunctory act required of all spurned lovers, cuts her hair in grief.

Yet, as if she doesn’t already have enough problems, she and a third of the people of her town are about to die suddenly and violently. For her, the experience is seamless: Mitsuha sees the comet explode on impact, awakens in the stone edifice (tomb?), emerges in the body of Taki, and comes to the realization of her death in the alternate timeline. She, too, makes her way out of kakuriyo and also pays the price of eventual forgetfulness.

Our heroes have borne the burden. How can they overcome their predicament? Were the Passion of Taki and Resurrection of Mitsuha all in vain?

Nonsense, says Shinkai, this is a story of salvation. Taki and Mitsuha will cooperate to rescue the residents of Itomori from their fiery fate. In a montage, close to the end of the film, we see the beneficiaries: friends, family, and a purposeful emphasis on Mitsuha’s high school nemeses – it rains on both the just and the unjust. Or, better yet, the net is cast wide.

It is also reasonable to assume that the Kami that protects Itomori has a hand in the planning of all this – the timing of the body swaps, Taki’s introduction to musubi and the kuchikamizake that makes the final exchange possible, and even the nature of the dreams of the Miyamizu shrine maidens that had been passed down through generations. It is not coincidence, but a purposeful direction of history covering dozens of centuries. This Kami is patient, after all.

But, back to our director. In his grand finale, the master of prestidigitation pulls yet one more trick from up his sleeve. Some critics and viewers, unaware of Shinkai’s past performances, found the ending to be predictable and trite, but for those of us who have travailed through Voices of a Distant Star and 5 Centimeters per Second and Garden of Words, the reunion of Taki and Mitsuha was anything but certain. He teases us with them passing each other silently, and every knowing heart in the audience screams, “No! You can’t end it like this! It isn’t RIGHT!” And the director smiles, and our favorite couple turn and realize their threads have become united once more.

It is a happy ending: all wrongs set right, death is overcome by sacrifice, the heroes accomplish their quest and regain their broken relationship in musubi-like fashion. What other story do we know that has in common all these facets and more? Don’t all our souls, consciously or unconsciously, relate to this narrative?

I think they do. And, while Makoto Shinkai takes a bow, there is a greater story behind him at work in the hearts of people, stirring their emotions, bringing tears to their eyes…. tears, why?

—

On average, Bob Aarhus finds an anime worth obsessing over every five years: NGE, Haibane Renmei, Madoka Magica, and now Kimi No Na Wa. Otherwise, he retired from the military and is now a full-time PhD student at George Mason University in northern Virginia.

This is awesome. Such a film rooted in surprise, turmoil, tragedy, and overcoming impossible odds deserves to be talked about and broken apart to analyze its intent, just like what was done here. Thanks for sharing–I’ll have to do the same!

I’m so proud to host this post – it’s one the best we’ve had here on the site. And absolutely, this movie is worthy of some strong analysis!

[…] connection, distance, and love work in tandem with many of the themes we discuss. It’s a meaningful film, and our site is all about meaning – in anime, in life, in […]

[…] This guest post was written by longtime support and contributor to our ministry, Bob Aarhus. I encourage you to also read his excellent article about Kimi no na wa (Your Name). […]

Great analysis, and well written!

[…] in a while when I wake up I find myself crying. The dream I must have had I can never recall. But… But… the sensation that I’ve lost […]

[…] Kimi No Na Wa: “Tears…Why?” […]